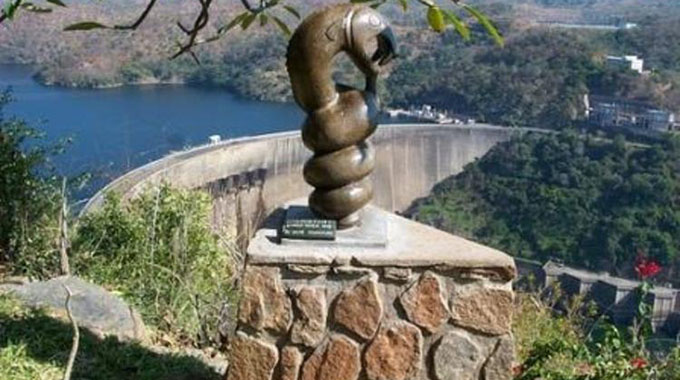

The rain-making ceremony that breathed life to Kariba

Isdore Guvamombe Assistant Editor

Cattle hooves pounded the ground as the boys drove them to the kraals at high speed in an impish attempt to beat the rains. But the heavy rains spattered, beating both the cattle and the boys silly.

The year was 1995 in Sampakaruma communal lands, under Chief Nebiri 300km south of Kariba town.

Grass-thatched huts totter with age, their mud-and-pole walls leaning backwards, with a little door that looks like the mouth of a village idiot.

More often than not, the thatch is dark brown with age, the weather and soot from fires forever lit inside.

The roofs are uncharacteristically low-hanging and the eaves almost obscure the doorway. The roofs are supported by several large, smooth wooden poles evenly distributed around the perimeter of the hut, itself the fecund of deforestation, itself a factor in climate change and its spiral effects.

In 1995, the October afternoon sun was angry and unforgiving. It spat blistering hot rays down the land and it was evident for the BaTonga villagers, leaving on the shoreline of Kariba Dam that the water was receding fast.

Cicadas clung precariously on Mopane tree buck, praying in merciful melodies to Nyaminyami, the river God and the ancestors for soothing rains.

Villagers sat under hut attics for a cooling shed. Dogs panted under the shed. Hens crackled while livestock spent time on the riverine vegetation, for the sprouting lush greens. Boys spent their time shooting birds with catapults or slings and hunting. Others trapped birds with the sticky paste. Boys also went swimming in the few remaining pools on Ume River (Bumi for the white man). Women washed clothes and bathed on selected spots on wells dug on the riverbed sand.

Ume River had dried and only Kariba Dam provided the much needed lifesaving liquid, for, all its tributaries had run dry and became serpents of sand. The villages were alive to their fate. Winter drinking binges had slowed down as villagers prepared for the summer cropping season. The experienced elders had started casting their eyes both in the sky and on the ground in search of signs of early rains.

Chief Nebiri in consultation with the elders in the BaTonga tribe decided to hold a rain-making ceremony. The Nyaminyami Rural District Council agreed to donated live elephants, buffalos, kudus and impalas to slaughter for the ceremony. Beer was brewed by elderly women in post mendicancy.

Within two weeks, the ceremony was held in binges that started with night vigils where a cross rhythm of drums, songs and dance was the mainstay. The final ceremony was held on the 14th night. Children were barred. The spirits manifested through their mediums in shriek but powerful voices.

There was intermittent meetings, songs and dances. Sacrifices in slaughtering the beasts and traditional relic were done. There was clapping, dancing, ululating, speeches by the occult. Question and answer. Beer! Beer… beer… beer and braai. By sunset, the spirits left their mediums, one by one into the world yonder but with one message, “The Rains would come, soon.”

The rain-making ceremony had been done and gone and the ancestors and God, had answered positively. As the afternoon proceeded an easterly wind started blowing. Conscious of the time factor, boys started collecting their cattle and goats for tethering and closing up at night.

A dark cloud formed fast and, suddenly lightning stabbed the air, followed by an ominous rumbling. Everyone realised the rainy season had come.

Cattle hooves pounded the ground as the boys drove them to the kraals at high speed in an impish attempt to beat the rains. But the heavy rains spattered, beating both the cattle and the boys silly. Soon they were both drenched. An extremely good rainy season followed, filling up Kariba dam.

“That year, Kariba dam filled up. You can ask anyone. From then up to now, the dam had kept water.

“I know many people do not believe in this but it worked for the community and everyone. Right now he community is considering another rain-making ceremony to save the dam,’’ said Never Gasho, who was the main officiant at the 1995, ceremony.

Today, talk is high among the villagers that there is need for another rainy making ceremony.

Scientists and Christian might dispute this narrative and attribute the droughts to something else, but for the BaTonga people, the rainy making ceremony is the solution.

Comments