The battle for Africa’s dream

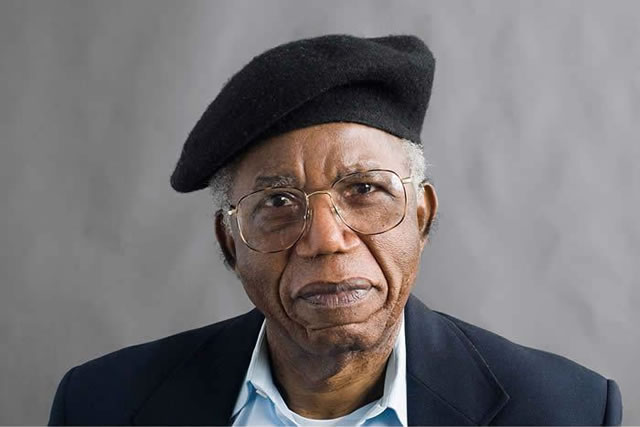

Joseph Ochieno

This is another 50th anniversary year for African history, 50 years since Dr Martin Luther King, Jr made the now famous “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington DC. I was recently gifted to listen to his daughter, Bernice Albertine King say, “my father saw racial injustice and economic injustice as twins . . .”

This statement of wisdom got me really thinking. Whereas so much has changed for the better for African-Americans since then, there remains a lot to do. A recent unemployment study suggests that African-Americans remain consistently, over the years, twice as likely to be unemployed compared to their white counterparts — a figure of 13,7 percent for blacks versus 6,7 percent for whites.

Furthermore, Africans suffer from both unemployment and underemployment. The former is, of course, made worse by an equally apparent educational disparity. Obviously, levels of education and the likelihood of employment and skills-build-up correlate, anywhere in the world. Even on this, the African-American fares at a similar level on the graph.

And while African-Americans constitute about 14 percent of the US population, they constitute over 40 percent of the prison population. That is six times the national average. Young African-American men without high school diplomas are more likely to go jail than find a job and, with it, the circle of poverty and family break-ups continues.

Effectively, there are more African-American men in prison than in higher education. Is it caused by a blame game, a defeatist attitude, denial or all three? That is not the focus of this piece. Noting Lord Paul Boateng became the first cabinet minister of African descent in Britain as recently as 2002, serving as Chief Secretary to the Treasury under Tony Blair, tells us a lot about Africa’s chief colonial master, her interests and relations with the continent.

Africans are these days, “freely” scattered around the world, in some cases by force, others by design, destiny or choice. Yet in almost all cases, whereas they might be free, they are certainly not equal.

Is it any wonder that in thinking deep, despite the usual reactions from the West, President Mugabe might have freely and fairly won the last elections in Zimbabwe after all?

Leading to those elections, Zimbabweans had two apparent choices: Either go with the neo-liberal Western-backed Morgan Tsvangirai of MDC-T, or stick with Robert Mugabe of Zanu-PF and his revolutionary path.

Impatient with the stagnation in the “willing-buyer, willing seller” land redistribution process in the country, President Mugabe opted for the “fast track” approach. It worked. Arguing from the premise that African economies are predominantly agricultural, President Mugabe stated, quite rightly, that an agricultural economy without access to land is not sustainable.

Land is the economy and the economy is land. It makes sense and, with African “land” hosting oil, grains, gas, water, timber, diamonds, gold, uranium, the argument is without doubt both morally and factually correct.

The landscape in Zimbabwe has been significantly changed from one of 4 000 white farmers to 245 000 previously landless African smallholders. But the most encouraging of the figures suggests that these resettled African farmers — who were, until recently, said to “not know how to farm”, now produce 40 percent of the national tobacco stock and 49 per cent of the country’s maize.

Threatened with continued sanctions from the West, the new government can almost certainly boast, “no hunger any more these days”: there is Brazil and there is India. And of course, they “discovered” China, well before most African countries woke up to the reality that these days, it is possible to bargain over resources on the economic high table.

For the West might soon need those resources even more — and if Africans play their cards right, that spells an economic transformation. — New African.

Comments