The absurd story of a man who was once ape

Christopher Farai Charamba The Reader

Absurd literature is one of my favourite genres. Of it Greig E. Henderson and Christopher Brown write: “Conspicuous in its lack of logic, consistency, coherence, intelligibility and realism, the literature of the absurd depicts the anguish, forlornness and despair inherent in the human condition.”

They add: “Counter to the rationalist assumptions of traditional humanism, absurdism denies the existence of universal truth or value.”

Human behaviour underpins most absurd literature and the best of its writers cause one to pose serious philosophical questions regardless of the form in which the writing takes, be it comedy or tragedy for example.

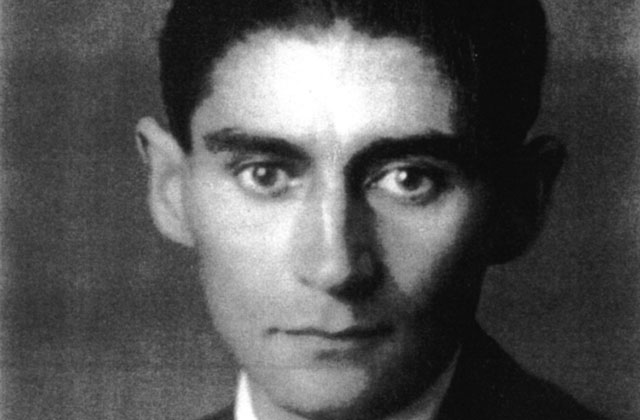

This reader was recently introduced to the absurdist works of the German novelist Franz Kakfa (pictured below).

Kafka was born to a middle class Jewish family in 1883 and would die 41 years later in 1924. He wrote all of his works in German and is said to have finished none of his full-length novels and burned around 90 percent of his work.

The discovery of Kafka was through the podcast Mostly Lit. One of the hosts spoke about the short story “A Report to an Academy” and so this reader looked it up and found it was right up his proverbial alley.

“A Report to an Academy” is about an ape, well a man who used to be an ape, who is asked to give a scientific account to an academy on his life as an ape.

Rotpeter, the name of the man formerly an ape, tells the academy that since becoming a man he has no recollection of what life was like as an ape but offers them what he remembers of his transition to becoming a man.

He narrates what he was told of his capture from the Gold Coast, that he was shot twice and put in a cage on a ship bound for Europe.

Rotpeter goes on to explain when he first gained some consciousness as a man, how he realised that there was no escape from the tiny cage and that the only “way out” was to embrace and imitate the life of man.

While Rotpeter found a way out of the tiny cage by becoming more human like, he however lost himself as a “free ape”, “In revenge, however, my memory of the past has closed the door against me more and more,” he tell the Academy.

His dilemma is that he is caught between two worlds as during the day he puts on this forced act that has become a part of him but at night he lays with a half-trained chimpanzee, a reminder of the animal kingdom from whence he came and also of this ruse he has involuntarily had to maintain. Rotpeter is not fully human but neither is he fully ape. He is neither captive in chains but he is also not free.

A common view on this story is that Kafka permitted his ape to be raised to a level of “humanness” as a means to illustrate the beast that exists within man or that the potential humanity of man could not be fully realised if he not free.

One is tempted to draw a comparison with Thomas Hobbes’ state of nature where there would be a war of all against all, under which he says, “the life of man (would be) solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. Reading this short story though, one couldn’t help but to see parallels with the slave trade and colonialism.

One cannot explicitly argue that this is what Kafka intended to portray, but under a context where Africans have been referred to as apes and a situation where Africans were captured and enslaved by Europeans and Americans, forced to change their names, forget their language and abandon their culture, the parallels are uncanny.

This absurd piece of writing was quite enjoyable and has enticed this reader to read more of Kafka, a process currently underway.

Comments