Thank goodness the silly sanctions season is over!

Tichaona Zindoga Acting Editor

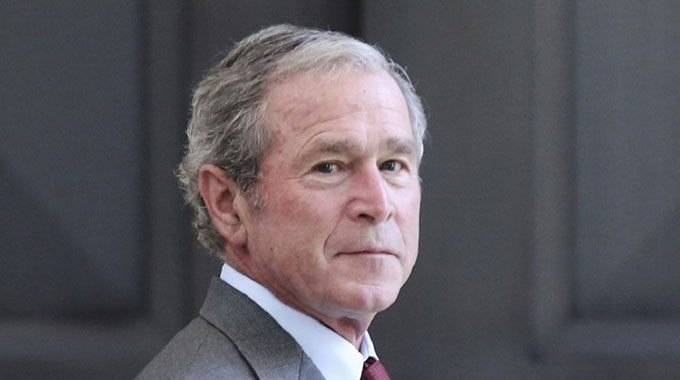

It is a strange feeling. The United States of America, the world’s most powerful country, has renewed sanctions against a poor Southern African country called Zimbabwe – and it is a relief that it has. Zimbabwe has been under US sanctions since 2001 when President George W. Bush passed the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act and gave the measures full effect via Executive Orders 13288 (March 2003), 13391 (November 2005) and 13469 (July 2008).

The Executive Orders are renewed annually.

Barack Obama, who became president in 2009, renewed these Bush babies until he left office in 2017.

Before he left office on January 20 that year, he made sure that the he extended the sanctions by another year, days before the 45th President of the United States, Mr Donald Trump came in.

And Mr Trump renewed the sanctions the following year, in 2018.

He has done it again.

On Monday 4, March, 2019, Mr Trump gave a Notice on “Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to Zimbabwe” wherein he outlined the history, justifications and targets of the Executive Orders on Zimbabwe and duly declared:

“The actions and policies of these persons continue to pose an unusual and extraordinary threat to the foreign policy of the United States. For this reason, the national emergency declared on March 6, 2003, and the measures adopted on that date, on November 22, 2005, and on July 25, 2008, to deal with that emergency, must continue in effect beyond March 6, 2019. Therefore, in accordance with Section 202(d) of the National Emergencies Act (50 U.S.C. 1622(d)), I am continuing for 1 year the national emergency declared in Executive Order 13288.”

Donald Trump

Declaring a “state of national emergency” is a nice way of declaring a war – or a war by another means.

Writing in the Washington Post on February 15 this year, Deanna Paul and Colby Itkowitz give some illuminating explanations as to the history and dynamics of national emergencies declared by the US.

They explain: “In 1976, Congress passed the National Emergencies Act, which permits the president to pronounce a national emergency when he considers it appropriate. The Act offers no specific definition of ‘emergency’ and allows a president to declare one entirely at his or her discretion.

“By declaring a national emergency, the president avails himself or herself of dozens of specialised laws. Some of these powers have funds the president otherwise could not access.”

Further: “Under current law, emergency powers lapse within a year unless the president renews them. A national emergency can be re-declared indefinitely, and, in practice, that is done frequently.”

There have been 58 pronounced under the National Emergencies Act, of which 31 are still in effect. Zimbabwe claims three of those – the only ones in Africa.

Paul and Itkowitz explain that US presidents have declared national emergencies since World War II with Bill Clinton having declared emergencies 17 times, George W. Bush 12 and Barack Obama 13.

“The vast majority have been economic sanctions against foreign actors whose activities pose a national threat,” we are told.

Essentially, a national threat is something that impairs the advantage of the United States regarding economic security, monetary security, energy security, environmental security, military security, political security and security of energy and natural resources, etc.

In our most innocent minds, the idea that a small country such as Zimbabwe could pose a threat to the mighty United States is almost laughable.

In all of the above-named sectors -from economic to natural resources -Zimbabwe would not ordinarily bother the US.

Or perhaps, it does.

Context is key: the Zimbabwe of the turn of the turn of the century represented an idea that threatened the existence of the global imperial hegemony – like a small fire.

Zimbabwe embarked on the land reform that reclaimed land lost to colonialism from Britain, the erstwhile imperial giant.

Even after 50 years of Independence, former colonies had maintained skewed land tenure systems that favoured the former masters such as Britain and France.

Additionally, they were economically reliant on them.

Independence had much dwelt on the politics and administration, not the wealth and economic distribution systems.

A Zimbabwe that reclaimed land threatened to correct the historical wrongs.

It would also send a signal to other African and Third World countries that land, wealth and resources could be successfully repossessed from the former masters to complete the story of Independence.

This would erode the legacy and material advantage of the former colonial masters and set altogether new rules of engagement between the North and South in today’s context.

Zimbabwe had to be stopped.

Outside of the grander politics of history and economics, the US had other material and present interests in Zimbabwe.

That is from capital to natural resources (including diamonds and uranium).

A rising resource nationalism, which Zimbabwe led, would destroy the dominance of not only former colonial masters, but also America itself as the global imperial master.

At the time, George W. Bush might have used some quid pro quo with Tony Blair, then British prime minister, as they straddled the world from Zimbabwe to Iraq.

He gave Blair the Zimbabwe sanctions.

Blair gave Bush the Iraq war.

Or something like that.

And since then, sanctions on Zimbabwe have been a major policy issue. Never mind how small Zimbabwe is.

There is no doubt as to the objects of the sanctions: at best, force (or coerce) Government of Zimbabwe to behave in a more pliant manner as to the demands of Britain and the US; or at worst cause the downfall of the government in question. It has been some kind of stalemate, though.

For the whole two decades.

Let’s say the US is inspired by something between seeking change of behaviour in Harare and outright deriving pleasure in punishing Zimbabwe.

Neither has worked.

Nor has it paid off for anyone.

Zimbabwe has lost probably US$50 billion to sanctions as it has deindustrialised, suffered disinvestment, lost businesses, lost markets, lost human resources, etc.

These have not transferred a net gain to the US: the US has lost opportunities to do business in Zimbabwe in various fields (which has gone to the Chinese, Russians, South Africans, etc); and has made some horrible decisions pouring money to regime change projects in the opposition and civil society.

Losses in the latter category are rather embarrassing and a public shame of how the US and the West in general have been fools with their money.

How, then, does one begin to feel a strange sense of relief that sanctions have been renewed?

The reason is that, sanctions and the threat of sanctions hangs uneasily over Zimbabwe like that proverbial Axe of Damocles.

The West itself uses sanctions as a negotiation tool and some kind of stick to beat Zimbabwe with.

The opposition, too, uses this external threat in their favour to try to browbeat the ruling party and cause instability.

It is known that the renewal of sanctions is seasonal.

The European Union renews sanctions – and they now want them called restrictive measures – around February.

The US follows in March.

It is a season.

Quite predictably, the opposition does a lot of provocation and grandstanding to oblige the extension of sanctions by the West during this period, giving Zimbabwe a lot of bad press.

For the opposition, the foreign hand is key.

The other side of the ostracisation and weakening of the Zimbabwean State by the West is the strengthening and sponsorship of the opposition.

The disturbances seen mid-January should be read in this context.

So, too, should be the August 1, 2018 post-election violence.

This year, the opposition had hoped not only for the maintenance of sanctions, but their deepening and expansion by both the EU and the US.

That has not happened.

It is small comfort.

What is likely to happen now is that, with the silly season of campaigning for sanctions over, the opposition will be more inward-looking and concentrate on internal issues such as the forthcoming congress and domestic affairs.

Until the next season, or some rare opportunity in between.

On the other hand, for a Zimbabwe that is still keen on dialogue, under President Mnangagwa’s re-engagement policy, it means diplomacy will be much quieter from now.

More gains can be recorded without the axe of sanctions hanging above.

Or the goading of the opposition, thankfully.

Comments