Surrogate mom gives Zim couple joy

Phyllis Kachere Deputy News Editor

Having been together for 10 years, six of them as a married couple, Mr Patrick Goredema and his wife Enitan have suffered the agony of realising that she is unable to carry a pregnancy.

Coming from a society where bearing children is viewed as the essence of family life, the Goredemas have not only suffered the agony of realising that she may never be pregnant; they have both suffered the tag of being a societal pariah due to fertility issues.

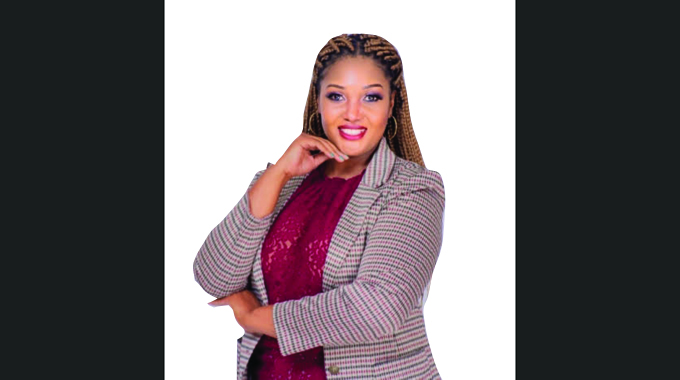

Love at first sight . . . Patrick and Enitan meet son Mudiwa for the first time

In an interview, the Toronto-Canada based couple narrated their agony on how they had to distance from some of their friends as the expectation for babies grew.

A few weeks ago, the couple was united with their son who was born in April through a surrogate mother in Georgia. They failed to witness his birth as Georgia closed its borders due to Covid-19 lockdown a few days before they could travel there in March.

Last weekend, the couple, together with their baby flew back to their home in Canada.

Harare-based specialist gynaecologist and obstetrician Dr Tinovimba Mhlanga said surrogate motherhood is a practice in which a woman (the surrogate mother) bears a child for a couple that is unable to produce children the normal way, usually because the woman is infertile or is not able to carry through a pregnancy.

Courtesy of BBC

While Mr Goredema has a child from a previous relationship, his wife had never had one.

“Some of our friends would constantly check on when the babies would start coming.

“It became an agony to constantly be asked, when are you guys going to have a baby? Because of the pressure that was creating on us, we decided to distance ourselves from them. And that was painful,” said Mr Goredema.

Mrs Goredema said they dated for four years before they got married.

“We obviously started trying for a baby soon after marriage and, a year, later, I could not conceive. We tried in vitro fertilisation (IVF — this is a process where an egg is combined with sperm outside the human body.

“The process involves removing an ovum from a woman’s ovaries and letting sperm fertilise it in a liquid in a laboratory).

“But twice, that failed. I was later diagnosed with endometriosis — (a disorder in which tissue that normally lines the uterus grows outside of it. The tissue can be found in ovaries, fallopian tubes or intestines whose common symptoms are pain and menstrual irregularities),” said Mrs Goredema.

Despite all that, Mrs Goredema, originally from Nigeria, defiantly hoped that she would one day conceive and carry through a pregnancy.

“Failing to fall pregnant took a toll on our relationship although my husband was quite supportive. Every month when I got my period, I would go through the cycle of grief.

“Acceptance, grieving about it! Every time during the end of the month when my period came, I would hope I would get pregnant the following month.

“And when the period came again, I would be like, Oh my God! It became a cycle, a painful cycle that you never get over.

“I always hoped I would eventually get pregnant and have my own baby,” she said, wiping away a tear.

Mr Goredema said those six years of trying for a baby was the most challenging time for them as a couple.

“Because we could create embryos, through IVF, I always believed there was a way out of this. At one time, my wife told me to find another woman who could bear children. That was the most painful time for me. As an African man, my society expects me to leave a bloodline, which I could not because of the fertility issues my wife had.

“I chose to remain with her while searching for ways to have a baby with her. I kept searching on the internet and I came across the surrogate motherhood programme that I then introduced to her. She was sceptical at first, but became enthusiastic.

“This was like new ground for us. We joined the programme and we were introduced to a wonderful surrogate mother who was more than happy and willing to assist us,” he said.

While they became enthusiastic about surrogacy, the uncertainty on the success of the surrogate motherhood created by unfamiliarity with the subject created more agony for the couple.

“We were not sure about how this would work for us. I had read about surrogate mothers who later changed their minds and fought to keep the babies. I did not know it would go for us. Fortunately, we had an amazing surrogate who was willing to assist us,” said Mrs Goredema.

Mr Goredema preferred an African woman to carry the baby and he tried South Africa and Kenya, but it turned out their regulations would not allow them to do so.

“This was something new that we were trying. We were not sure what would be the results if a woman from a different race would carry our baby. But as we got more information, we finally settled for a Caucasian surrogate mother in Georgia. We had to ask her if she was comfortable carrying a black child, and she told us that she was more than willing to assist us,” he said.

When asked about the features of their new baby, Mr Goredema said; “Our baby has our features. The egg that was fertilised came from my wife and the sperm from me. The baby looks like my wife although he has my big African nose.”

He said Georgia became a favourite as their regulations allow for the name of the baby’s mother to be written on the birth certificate instead of the surrogate’s name.

Mrs Goredema said although she had a choice between a known surrogate mother and a stranger, she chose a stranger as this eliminated social complications that may arise through familiarity. Because of Covid-19, the Goredemas failed to travel to Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia to witness the birth of their son in March.

However, they eventually got there a few weeks ago but had to be quarantined before they could see their baby.

“Having to wait to see our son for the first time while we were in quarantine was hectic. We just could not wait. The night before we could meet our baby, my wife told the doctor at the hospital where he was being kept that we would be there by 7am. And the doctor told us they would only open at 9am,” chuckled Mr Goredema.

As part of preparations to meet her new born son, Mrs Goredema said she wore make-up and chose her best clothes!

“When we arrived at the hospital, I kneeled and thanked them and the nurses and medical staff were surprised and kept telling us there was no need for that. But I had to thank them for caring for my baby as I could not be there on time. I am for ever grateful to the woman who helped carry our son’s pregnancy,” she said.

Health and Child Care Ministry Acting Chief Director Curative Services Dr Maxwell Mareza Hove said there is a gap in terms of guidelines for surrogacy in Zimbabwe.

“The only available guidelines are for in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) and sperm donation. The Medical and Dental Practitioners’ Council has to come up with those regulations to fill in the gap on surrogacy. Those that are doing it are unregulated. When these Council has formulated these guidelines, they will then be elevated to become policy,” said Dr Hove.

Information gleaned from internet shows that there are two types of surrogacy-traditional and gestational.

In traditional surrogacy, a surrogate mother is artificially inseminated either by the intended father or an anonymous donor. She carries the baby to term and that child is genetically related to both the surrogate mother who provides the egg and the intended father or anonymous donor.

For gestational surrogacy, an egg is removed from the intended mother or anonymous donor and fertilised with the sperm of the intended father or anonymous donor.

The fertilised egg or embryo is then transferred to a surrogate who carries the baby to term.

The child is genetically related to the woman who donated the egg and the intended father or sperm donor but not the surrogate.

Dr Mhlanga said while Zimbabwe does not have surrogacy in its constitution, the country has registered four success stories.

“Our constitution does not have anything mentioned on surrogacy. We are regulated with good clinical practice and follow regulations from other countries.

“We have registered four success stories to date. And the babies are; two years, six months, three months and two months old,” said Dr Mhlanga.

He said the process is a simple one where one comes for consultation. If she cannot carry the pregnancy or in cases where carrying a pregnancy becomes a danger to one’s life or in cases of recurrent miscarriage, a patient is then recommended to have IVF done.

“One is given an option to look for a surrogate or the clinic will provide one. What follows is process where the biological mother is stimulated for egg harvesting and the surrogate is prepared to receive the embryo. This is done at the same time.”

He said the general qualifications for surrogacy are that one has to be in good mental and physical health, have carried and delivered at least one child and should be living in a stable situation.

A would be surrogate mother, must be less than 43 years of age and must have had pregnancies that were free of complications and were full-term. She must not be a smoker or abuse alcohol.

Dr Mhlanga explained that being a surrogate is an altruistic act that does not require payment although the medical costs associated with pregnancy have to be borne by the person who has contracted the surrogate mother.

He said it was almost impossible for a surrogate mother to refuse to hand over a baby as there are strict vetting and practice regulations.

Comments