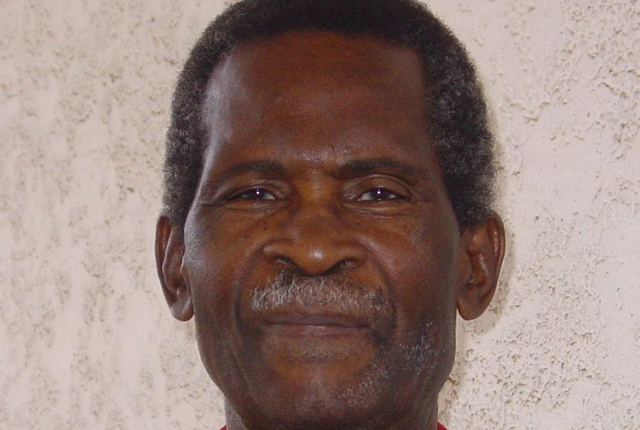

Saidi a journalistic giant among midgets

Geoffrey Nyarota Correspondent—

Yesterday a legend of newspaper journalism in Zambia and Zimbabwe was laid to rest in the city of Kitwe, in the Republic of Zambia, where he died two days into the New Year last week while visiting.

The late William Sylvester Saidi, who became an icon of journalism in a career spanning a drama-packed 60 years in the two countries, was born on May 8, 1937 at St David’s Mission in the then Chihota Tribal Lands, south of Harare. He grew up and went to school in Salisbury’s then dusty township of Harare, now Mbare and dustier.

William was the only child of Evelyn Chidzetse of Makawe Village in Seke District and an immigrant worker, Agonilepi Matola Saidi, who originally came from Mangochi on Lake Malawi. He settled in Harare, where he became a tailor.

While among colleagues in Harare and Bulawayo Bill Saidi appeared to lead the life of a recluse; he married and divorced twice. Each of his ex-wives bore him three children. The second spouse, Beauty Masenga, lives in Kitwe, where he died. Saidi leaves behind six children, 15 grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Three of Saidi’s children live in South Africa, while two are based in the United Kingdom and the sixth lives in Chitungwiza.

Bill Saidi filed his first article as a young reporter on the African Daily News at age 20 in 1957. A total of 60 years later in 2017 Bill Saidi died four months short of reaching the ripe old age of 80. He was still contributing articles to the third generation Daily News, of which he was part of the original team of founding editors back in 1999, along with Davison Maruziva and I. Saidi’s career as a journalist flourished in Zambia, the country which became his adopted home for a total of 17 years and where he died last week while on a visit.

Saidi’s reputation as an intrepid and enterprising journalist who was denounced in public by President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia preceded him on return to Harare, where no scribe had achieved similar distinction. It was a status that was to influence the path of his career in Zimbabwe under the direction of the young nation’s wary politicians.

The attack on Saidi by President Kaunda at a Press conference was a ground-breaking incident that Saidi spoke of or wrote about with elation in newspaper articles after his return on Zimbabwe’s attainment of independence in 1980. On repatriation Saidi embarked on an illustrious career, spanning both the then just Government-acquired Zimbabwe Newspapers, as well as the privately owned Horizon Magazine and the newly established Associated Newspapers of Zimbabwe, publishers of the Daily News, of which I was founding Editor-in-Chief.

We appointed him Assistant Editor at the launch of the paper in 1999. When the Daily News on Sunday was established in 2003 he was appointed founding editor at age 66. He held the position for a few months. The paper was banned by Government soon afterwards after the company’s chief executive officer, Sam Sipepa Nkomo, who had just been appointed, defied the editors and refused to register the two newspapers, as required by the law.

Saidi’s career as a journalist was marked by three characteristics. He exuded a fearlessness of approach as he sought to tell the story without fear or favour, a certain nonconformist streak which questioned unnecessary authoritarianism as well as an extraordinary command of English, the language in which he found his legendary expression.

For a man who was not a scholar of particularly outstanding erudition, Saidi’s wordplay was truly remarkable. He was a veritable wordsmith, a linguistic giant whose outstanding skill could have been exploited in refining the writing skills of young journalists. Sadly, this did not happen and Zimbabwe’s journalism remained the poorer for this gross oversight.

My first close encounter with Bill Saidi on a daily basis was in April 1983 after I was promoted from the position of editor of The Manica Post in Mutare to assume the reins at The Chronicle in Bulawayo during the turbulent years of Gukurahundi in Matabeleland. Saidi was the editor of Sunday News, the sister paper of my new charge.

The doors to the offices of the two editors were less than one minute apart. I was 32. Saidi was 46. He towered above me both in terms of his physical stature as well as in terms of his professional experience as a journalist and his reputation.

Though he was gentle in his demeanour, I felt intimidated in his presence. He was hardworking, soldiering on for hours on end in the time-tested manner of good editors on weekly newspapers. Saidi was the proverbial glutton for punishment.

He regularly reminded me of Boxer, the hardworking stallion in George Orwell’s “Animal Farm”, who worked day and night at the windmill as the project was constantly sabotaged by the neighbouring farmer. This he did while the new rulers on the farm, the pigs, wined and dined in the farmhouse where they had taken up residence against the tenets of the new constitution of Animal Farm. They were enjoying the same excesses of luxury that should have gone with the evicted former owners, the humans.

Saidi was an inexorable stickler for decent journalism, always striving for credibility while guided by the tenets of ethical practice, truth, fairness, justice, including always recording the other side of the story where allegations are made, regardless of how difficult or how long it may take to obtain that other side. He always disparaged the popular excuse of today’s journalism, often false, as espoused in the oft repeated statement, “At the time of going to press the accused party was not available to provide comment.”

Because of our proximity, Saidi played a part in modelling my own career as a newspaper editor. I was always conscious of his overbearing presence. I had my own deputy, Martin Lee, about the same age as Saidi, and assistant editor Don Henderson on Chronicle. But oftentimes it was Saidi that I consulted because of his more appropriate experience in an environment where our newly empowered black politicians had become a dominant factor of both politics and journalism. Many decisions I took were on the basis of whether Saidi would approve from a professional point of view.

And so it was when we subsequently found ourselves both at The Financial Gazette and at the Daily News where I served as editor with Saidi in some senior editorial position, but more importantly, as an influential columnist who was loved by most readers and reviled by the majority of politicians.

At The Financial Gazette, publisher Elias Rusike, now late, was in the habit of calling me on the intercom from his office on Thursday mornings as he went through the issue of the newspaper.

“Does Bill Saidi not have anything else to write about other than Zanu-PF and the one-party state?”

“But our sales are going up all the time,” I would tersely remind the boss.

Back at Chronicle at the beginning of what became known as the Willowgate Scandal, I sat down with Saidi who was visiting from Harare. I briefed him in detail about the intricacies of the scandalous corruption in which we had caught several top Cabinet Ministers and other Government officials with their proverbial pants down or with their equally proverbial fingers in the till.

“And you want to publish all that?” Bill asked, voice booming.

After I assured him that we were convinced of the veracity of all our information, never mind how far-fetched it might appear, Saidi was silent for a while.

The he said, “Well . . .”

I have always wondered, if my life and that of Davison Maruziva, my deputy at Chronicle, might not have taken totally different directions had I heeded the cautionary tone in Saidi’s voice that hot October day back in 1988 and spiked the story. But on that day I was somehow convinced that he approved.

We spent many more years in closer proximity at the Daily News. The Willowgate Scandal was ground that we hardly ever revisited. But it was always there at the back of our minds as we charted new investigative terrain. On one occasion we were arrested and locked up together at Harare Central Police Station in the company of journalists, John Gambanga and Sam Munyavi, now late.

The Daily News had published an article, which was an eyewitness account of police vehicles ferrying property stolen from an occupied commercial farm.

The police hierarchy was far from amused but what we published was the copper-bottom truth, backed by indisputable evidence, images recorded by our photographer. I believe this was Bill’s first arrest. He too was far from amused and he left no one in the Law and Order Section at Harare Central in any doubt what he thought about them.

Any journalist who addresses issues of interest, importance and relevance to the public will make his newspaper’s readers happy, especially if he or she does so professionally, while digging deep where other reporters merely scratch the surface, and presents his or her findings while waxing lyrical, as Saidi would put it, in well executed articles. No journalist will ever please all readers, however.

So it was with William Sylvester Saidi.

On Sunday News his most popular or notorious column, depending on the reader’s political conviction during that turbulent and extremely politically polarised period, was A View from the Matopos by Muchandida Madoda. His provocative half Shona and half Ndebele moniker had some readers nearly tearing their hair out, had it been possible, in anger. Rendered into English, Bill’s vexing name meant, “Gentlemen, you have no option but to like me,” with a silent “whether you like it or not” implied.

Some of the content of the column and the pseudonym did not endear the writer to some of his readers. Within a day of his death last week one journalist of a later generation asked a question about some of the articles that he penned in the column. But the futility of asking Saidi any question that he was no longer at hand to respond to; a question raised after his death with regard to issues he addressed more than three decades ago, became all too evident.

After he was relieved of his position at the Sunday News, no doubt because those who walked in the corridors of power were finding his output increasingly unpalatable, Saidi was appointed Group Features and Supplements Editor at head office.

He headed a department that was principally created for him. Editor Farayi Munyuki, however, allowed him to continue to do that which he passionately loved to do — to inform, challenge and provoke readers in a weekly column, this time under the more appropriate nom-de-plume, Comrade Muromo, or Comrade Mouth in English.

On the Daily News subsequently Saidi continued to wax lyrical in a weekly column, which we humbly christened The Bill Saidi Column, not that there was anything meek about his weekly outpourings, even as advanced age took its toll on the illustrious Saidi.

I have always entertained the belief that any man who is maligned by the weekly tabloid, The Patriot, must be a progressive and patriotic citizen.

In its issue of 29 May, 2015 The Patriot characterised Saidi as “a pauper who suffers from the Kwashiorkor of failure to embrace the freedom that independence brought to him and the rest of Africa’s progressive minds”.

Saidi soldiered on, guided by his own ideals of democracy, fairness and justice.

The Patriot was correct though in characterising Bill Saidi as a pauper, but only in the sense of being totally impecunious after he devoted 60 years to active journalism. Up to the time of his holiday in Zambia, during which he succumbed to death in Kitwe, Saidi was still an active columnist in the Daily News, a role he played going back to the founding of the newspaper in 1999, when he was appointed Assistant Editor.

At the time of his departure for Zambia he was filing his contributions from an Old People’s Home in Bulawayo. Those familiar with Saidi’s inimitable style of delivery must have detected a certain decline towards the end, compounded no doubt by the failure of a younger generation of sub-editors and proof-readers to correct elementary typos.

His last active stint was at The Herald where his venerated career on return from Zambia started. This second and final stint at Zimbabwe Newspapers was far from the powerful office of an editor. He was back at the coal-face of journalism as a sub-editor and proof-reader, doing on The Herald that which he enjoyed to do most passionately — ensuring that stories were well written and in immaculate, if somewhat flamboyant, turn of phrase.

“My English could be pompous,” Saidi once said of his younger days as a journalist, “for I was under the mistaken impression that if you used jawbreakers your stock rose among the Europeans.”

In one of his countless articles Bill opined about the profession he so much loved: “It is healthy for all of us in the fraternity, whichever side we are on, to remain close — not to the extent of exchanging valuable corporate secrets or explosive ‘inside’ titbits. We should cultivate the sort of familiarity that ensures we recognise how great it is to build the nation”.

“This is to know that there is no formula that could set us apart — a formula of THEM vs US, two camps fighting like dogs over a piece of discarded meat. We are all on one side — perhaps not the side of the angels, but The Good Side — the side that wishes the country well, that would not betray the country for anything, the side that would not conceal any dark secrets from the people, or anything that is going on everywhere in their country, including its darkest, ugliest side.”

While steeped in the hurly-burly of an active career in journalism, Saidi found time to craft the manuscripts for and churn out more than six books. They included “The Hanging” (1978), “The Brothers of Chatima Street “(1990), “Gwebede’s Wars” (1989), “Return of the Innocent” (1979), “Day of the Baboons” (1988) and “A Sort of Life in Journalism” (2011).

In his younger days he also found time to perform with the Milton Brothers, a Mbare-based musical outfit.

In conveying condolences to the Saidi family, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), often the target of Saidi’s acerbic pen, stated: “His works helped shape our greater society in a positive way and we shall forever cherish and celebrate a life well lived to benefit humanity in one different way. The mother party wishes Saidi a well-deserved peaceful rest eternally as we celebrate the lasting legacy he leaves behind. May his dear soul rest in eternal peace.”

Bill Saidi was a gentle giant among many professional midgets. Raised entirely in the ghetto in the poverty-stricken Old Bricks, Jo’burg Lines, New Location and National sections of Mbare, he devoted six decades of his life to professional journalism.

He died a poor man, officially a resident of Chitungwiza, far away from the opulent lifestyles of the corrupt politicians he routinely lambasted. Saidi and I had an unwritten pact that, whoever was called by the Lord first, the other would deliver a graveside eulogy.

Now I lament that, for reasons of the same post-journalistic poverty, I could not travel to Kitwe to deliver on my side of the bargain. Go well Bill Saidi.

(Geoffrey Nyarota is former editor of The Manica Post, Chronicle, The Financial Gazette, Daily News and The Zimbabwe Times Online. A multiple award-winning journalist, he is a Fellow of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University.)

Comments