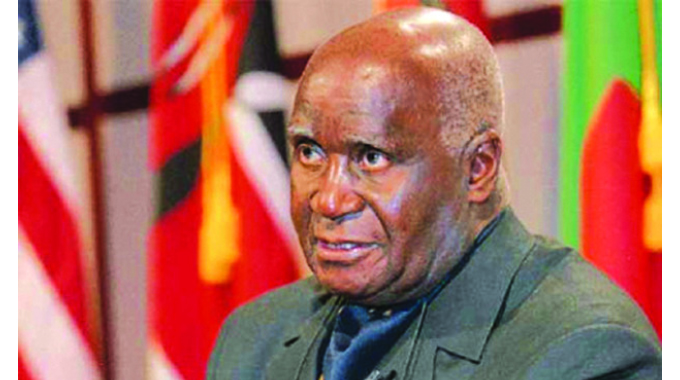

Remembering Zambia’s founding father Kaunda

Michael T. Kaufman

Kenneth David Kaunda was born on April 28, 1924, at a Church of Scotland mission in the northern part of what was then Northern Rhodesia.

His father, David, had been ordained in the church and worked at the mission as a teacher.

His mother, Helen (Nyirenda) Kaunda, had been one of the first African teachers in the region.

Kenneth, the youngest of six children to survive childbirth, was born in the 20th year of his parents’ marriage.

They nicknamed him Buchizya, or “unexpected one.”

Kenneth Kaunda became a teacher and a school headmaster and worked as a welfare officer at the giant Nchanga Copper Mine.

He often travelled around the country on his bicycle with his guitar strapped to his back, stopping to sing hymns and discuss politics with tribal chiefs and others, and establishing branches of a Black organisation called the Northern Rhodesia African National Congress.

On one trip, in 1952, he encountered a lion.

“I must have been about 20 yards from it when I stopped,” he wrote in his book ‘Zambia Shall Be Free’ (1962).

“It continued to stare at me without making the slightest movement. I rang my bicycle bell and shouted, but it stood still and stared at me. I took my cycle pump and hit almost every part of my bicycle, but the animal did not even wink as far as I could see.

“I don’t know why,” he continued, “but all of a sudden I lifted my heavily laden bicycle as if to cross a stream without a bridge and waved it over my head with both my hands. This was too much for the king of beasts; he made one leap and disappeared.”

The story of his intimidating a lion spread through the country, enhancing his reputation.

He drew a following with his speeches against the colour bars of the colonial period.

He studied the teachings of Gandhi, accepting his call for non-violence and asceticism.

Already a non-drinker, Mr Kaunda gave up cigarettes and meat.

After the white-run Federation of Northern and Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland held an election in 1958, he was arrested and jailed for leading a boycott against it, and his organisation, the Zambia African National Congress, was banned.

In the several months he spent behind bars — the “most difficult months of my life,” Mr Kaunda said, during which he endured malaria, dysentery and other ailments — his commitment to non-violence grew stronger.

“I realised it is no good trying to lead my people to the land of their dreams if I get them killed on the way,” he later told an interviewer.

He was freed on January 8, 1960; three weeks later he was elected president of an organisation he had formed, the United National Independence Party, which quickly became the largest party in Northern Rhodesia.

Over the next three years, white settlers, Black nationalists and the British government haggled over Northern Rhodesia’s future.

The settler minority wanted the country to be part of a new amalgam, to be called the Central African Federation.

Against this backdrop, Mr Kaunda organised civil disobedience campaigns and strikes.

At one point he publicly burned his identity papers and declared that the British government could either “build more prisons or grant our legitimate rights.”

But he was hardly a firebrand by disposition.

“In private he speaks so softly that listeners must often strain,” a profile in The New York Times said, adding that he was “gentle and self-effacing” and “neither smokes nor drinks and lives chiefly on vegetables, fruit, milk and water.”

He had married Betty Banda when he was a schoolteacher.

She actively supported his political career and was known to Zambians as Mama Betty.

She died in 2012. They had three daughters and six sons.

Year-by-year under Mr Kaunda’s leadership, black people gained increasing participation in the colonial legislature.

Finally, in January 1964, the first elections were held in which all residents, white and black, had the same voting power.

His party won in a landslide, and Mr Kaunda, at 39, became the Commonwealth’s youngest prime minister.

On October 24, 1964, following an agreement with Britain that had been struck in May, the British protectorate of Northern Rhodesia became the Republic of Zambia, with Mr Kaunda as president.

After leaving politics, he kept a public profile.

An avid ballroom dancer — Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Britain had been one partner — he even made a surprise appearance in the studio audience of the American television show “Dancing With the Stars” in 2006.

Mostly, however, Mr Kaunda remained a voice in public affairs, and though his opinions were sought less frequently in his last years, he savoured the attention when they were.

“I have a duty to come and point out things,” he told The Times in 2002. “I have been pointing them out to great crowds, sometimes to wild cheers, sometimes to deafening silence. I’m not sure I have brought joy to many a heart in authority. But it’s out of love of my country that I’m saying these things, to set things right.’’

Michael T. Kaufman, a former foreign correspondent and editor for The Times.

Comments