Remembering Lillian Masitera, pioneer of self-publishing

Joyce Jenje Makwenda Correspondent

Lillian Masitera, a standard bearer of self-publishing in Zimbabwe, died on February 6, at Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals.

She had not been well for some time. Zimbabwe’s arts and culture industry is poorer without her.

I had last seen Masitera a month or so ago, and she had been communicating on WhatsApp about her latest book, “Customary Shambles” on the Zimbabwe Women Writers (ZWW) group chat.

Lilly, as she was affectionately known, is one of those few writers who had the self-confidence to challenge the monopoly of established publishers.

Back in the 1990s, as it still is now, it was not easy to have one’s works published, depending on the yardstick that the publishing house was measuring your work with.

Sometimes one’s work would fail because the publisher was having a bad day or simply they were not interested, or they could not see commercial success in your work, in the local market.

Consequently, many Zimbabwean writers feel the artiste in them being killed because, like all artistes, one thing that gives writers satisfaction is to see their works out there, whether many people will actually buy them or not.

The most important thing is to make sure that the works have been shared and appreciated by those who care.

Masitera did not want to keep her writings to herself, she wanted to share her literature at all costs. She ultimately decided to publish her works on her own.

One has to be brave and dedicated to their writing in order to do this, as it can be time consuming and stressful.

Masitera paved the way for self-publishing for many local writers. I am one of those who followed in her footsteps. Although some of her books were published by publishing houses, most of them were self-published.

To date, she published six books. “Militant Shadow” (poetry) — 1996/2012, was published by Minerva Press, the 2012 edition was self-published.

“Now I Can Play”, “The Trail”, and “Start With Me” were self-published.

Her other book “Saskam Express” was published by Lillian with the support of Culture Fund, in partnership with the Embassy of Sweden. And “Customary Shambles” was published, primarily as an e-book, by Blue Diamond Publishers.

But how did Masitera become the author that we know today?

When Lillian — who came from Bikita District, but schooled in Macheke, before training as a teacher in Gweru and later studying at the University of Zambia — was writing letters to her family and friends, she did so creatively.

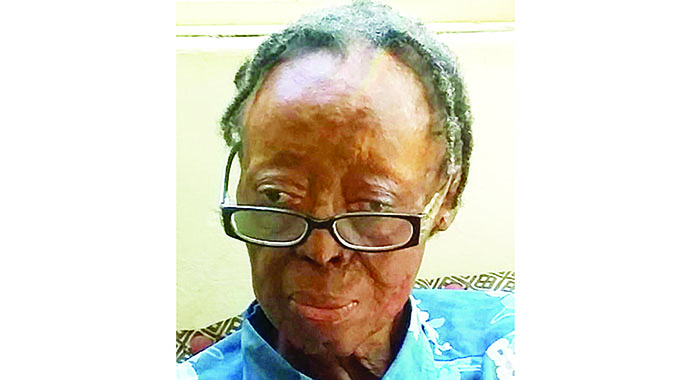

Lillian Masitera

“I was writing letters to friends and relatives before the era of e-mails and text messages. And some of them would later get back to me and say: “You know I still read your letters, now they are old. Why don’t you compile them because I find that I have to go back to what you said before, because there is always something in it, maybe some joke that I still find fresh when I come back after a year. So friends were saying we don’t throw away your letters,” said Lilian in an interview that I had with her in 2015-2016.

To her, they were just letters, but the way she wrote them and the fact that her family and friends would like to go back to reading them, meant that she had a unique and engaging style of writing.

Masitera also started reading books by other people.

“I had a special liking for Charles Dickens when I was in Secondary School, so I would read and say wow, and I would also go back to this book even after exams, (because) certain passages were really inspiring,” she said.

“So then with that I also thought, if people read my letters and enjoy them, and I am reading other people’s writings which is in book form and I enjoy it, maybe there is something to it. I cannot always be writing letters to friends, but I want to communicate with other people in written form, so maybe I should put my ideas in writing and try to compile something.”

Masitera’s publishing career began with poems printed in the early 90s in a number of local magazines and collections, including Tsotso, (a magazine of new writing in Zimbabwe), she also had poems published in The Journal on Social Change, and anthologies published by Zimbabwe Women Writers.

In 1995, her poem “Enter the Teetotaller” was also included in “After the Storm”, a huge collection of poems published by the US National Library of Poetry.

For this, she was awarded the International Poet of Merit Award, by the International Society of Poets, in Washington DC, USA, in July 1997.

Her poem “Framework” was translated into German and published in “Antilopenmond” (“Antelope Moon: Love poems out of Africa”) by Peter Hammer Verlag, in 2002.

Masitera was first published in her own right when 35 of her poems were published in England by Minerva Press, under the title “Militant Shadow”. The anthology’s theme revolves around the trials and tribulations of women’s day to day lives and women’s empowerment.

“Ideally, it is intended to arouse awareness that certain things that you take as a given, for instance that is what God wants from a woman and do not expect anything else are, in fact, socially constructed for women to adhere to, and they have to de-construct those notions/structures for the better,” she explained.

“Militant Shadow” was a success, but she regularly had to buy copies of the book and have them shipped from the UK to Zimbabwe, at personal cost, which became problematic for her.

She decided from then on she would have her books published in Zimbabwe, one way or another.

Meanwhile, Masitera started writing short stories, one of which was translated from English to Shona, in a collection called “Masimba”, published by Zimbabwe Women Writers (ZWW). Two of her short stories were also published by the College Press in another anthology — “A Roof to Repair” — with four other local writers, including Memory Chirere.

Masitera felt encouraged and now wanted to have her own collection of short stories, but just like her poems, local publishers were arguing that they did not have a market for such.

“I was disgruntled with the fact that again short stories were like poems, you had to have short stories together with other writers in order to be published by local publishers,” she said.

“They did not want a collection of only one person’s short stories. Some publishers were arguing that they don’t have a market. I decided that maybe I should try and publish myself locally.”

And that’s exactly what she did.

While Masitera was successful with self-publishing, the biggest problems were always marketing and distribution, which are not only a problem for independent publishers, but even established publishing houses.

But as an individual, it can be overwhelming.

“I think the main challenge is the financial aspect because it’s quite a costly exercise. But the second one is the marketing aspect, because if you publish something yourself you get all your copies delivered, the whole pile, however many you have ordered. You need now to distribute them in the shops,” Masitera said.

“You need them now to be known, to exist. How are you going to do it? Do you put an advert in the newspaper? Do you stand at the intersections and give out pamphlets so that people know? People have to know that your book exists for them to buy. That is quite a challenge. To me I think the marketing is harder than looking for money to publish it yourself.

“Because you may have saved resources, especially if you are working. You may have donors who sponsor the book and so forth. But distribution is simply a nightmare: you need the transport, you need time, you need manpower, to get the book known. You need to go out to the media, so that you appear, whether on TV or radio. People have to know that there is such and such a book for them to then look for it.”

While she faced challenges in the writing business, Masitera soldiered on as she felt she had to keep de-constructing what has been constructed by society “to keep women in their place”. She encouraged women who want to write to be disciplined.

“So, first of all, someone has to have the drive and if they have it, they start writing, the writing itself takes a lot of discipline,” she said.

“You really have to say now I have to do something. I am really going to weave out something. I am going to carve out this thing. I want to design and create this thing, so that requires devotion.”

As I am reaching the end of this article, it is dawning on me that you have transitioned. I stop for a while, I sigh, but I find solace in the fact that Lilly; you left us a legacy that we are proud of! Lilly’s partner John, family and friends please find comfort in that Lillian is still with us through her many works.

Continue to write in that land where we don’t see you, to question and de-construct the obstacles faced by Zimbabwean women.

And we will continue to explore and feel your works.

Thank you Lilly, ufambe zvakanaka! Go well Lilly!

Joyce Jenje Makwenda is a researcher, archivist and author. She can be contacted on [email protected].

Comments