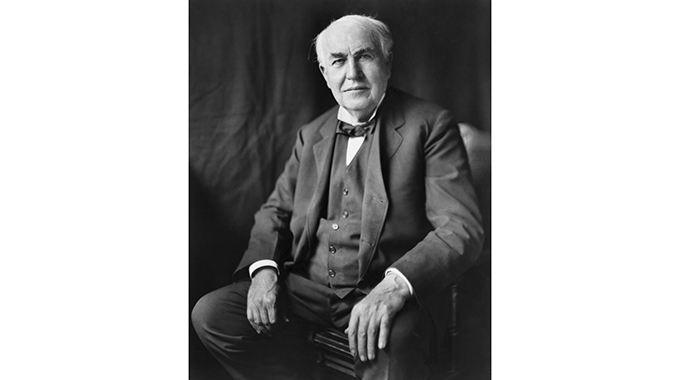

Remembering Edison, the incandescent inventor

David Oshinsky Correspondent

Edmund Morris died this past May of a stroke at the age of 78, having written the final sentence of “Edison” (2019) several months before. Composing in long hand and obsessed with the craft of writing — he considered 300 well-chosen words a day to be his productive limit — Morris was known for taking his time. His magisterial trilogy of Theodore Roosevelt, published over a span of three decades, won him a Pulitzer Prize for Volume 1. His next project, “Dutch”, a 14-year journey into the mind of Ronald Reagan, earned him something perhaps more coveted than a Pulitzer: a US$3 million advance.

Given free run of the White House and unparalleled access to Reagan himself, Morris came down with a severe case of writer’s block. He couldn’t get a handle on the president, whom he found inscrutable and “simply boring.”

To liven things up, Morris added a handful of fictional characters (the lead one named “Edmund Morris”) to stand by Reagan’s side and tell his story in a more memorable way.

The reviews weren’t kind.

Thomas Edison presents few such problems. A figure of astonishing brilliance and manic productivity, he cared so little for the feelings of other people (save the big investors who bankrolled his ventures) that he saw no reason to keep anything bottled up inside.

His archive runs to five million pages, including the pocket notebooks he carried everywhere to record the ideas that came in torrents, and the brutally frank letters he wrote about the failures of immediate family members he otherwise studiously ignored.

Were it left solely to Edison, he would have locked himself away in his lab, emerging every few months to announce yet another miraculous discovery. “His need to invent,” Morris says, “was as compulsive as lust.”

For some unexplained reason, Morris decided to write this saga in reverse, beginning with Edison’s final years and working backward to his birth in small-town Ohio in 1847. It’s the biographical equivalent of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”, though Fitzgerald had the good sense to make it a short story, while Morris’s “Edison” comes in at just under 800 pages, including footnotes.

Some readers may see the device as gimmickry, following in the questionable footsteps of “Dutch.” At a minimum, it takes some getting used to, because we’re never quite certain how one event builds upon another or whether a character who appears early in the book (but late in Edison’s life) is central to the story.

This leads to a lot of flipping back and forth through the chapters, with a heavy reliance on the index to keep things straight.

As with Teddy Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan, Edison’s accomplishments are familiar. Biographies of him already line the walls of libraries, the most insightful being “Edison: A Life of Invention,” by Paul Israel, who directs the project to edit and digitalise Edison’s archive, now in its 41st year.

Writing about someone who filed more than 1 000 patents, whose inventions ranged from incandescent electric lighting to immovable concrete furniture, who personally tested 15 000 native plants in a failed attempt to produce a domestic rubber supply, demands a working knowledge of electrical engineering, chemistry, radiography, metallurgy and botany — all of which Morris readily acquired. What is missing at times is the discipline needed to keep the main themes of the story in focus.

A prodigious researcher, Morris leans heavily toward the “more is better” school of biography. Loath to ignore the fruits of his archival sleuthing, he throws almost everything into the mix, leaving it to the reader to assume the author’s role of separating the important from the tangential.

Few biographers, however, possess the narrative talents of Edmund Morris. His ability to set a scene, the words aligned in sweet rhythmic cadence, is damn near intoxicating.

What set Edison apart, he notes, were the traits and habits — “contrary thinking, obstinate repetition, daydreaming, delight in difficulty” — that enhanced his God-given intellect. Edison’s father, stubborn, contrary and fiercely libertarian, had bounced between the United States of America and Canada to elude authorities from both countries who thought him obsessively disloyal.

His mother, meanwhile, encouraged his love for books as well as his basement chemistry experiments, even when they threatened the living quarters above. She “was the making of me,” Edison recalled. “She let me follow my bent.”

Edison began inventing in his teens. His first major invention, a quadruplex telegraph that allowed stations to send and receive messages simultaneously over the same wires, earned a handsome profit.

But another personal favourite, an automatic vote tabulator for legislative bodies, flopped badly. “Speedy voting was the last thing politicos wanted in the passage of bills,” Morris writes. “Edison resolved that hereafter he would invent only things that people wanted to use.”

That list included the first method for recording sound, making motion pictures and providing electric lighting to the masses. Much of it took root in the enormous industrial research and production complex Edison created in West Orange, N.J. — a place where anything could be built, he boasted, “from a lady’s watch to a locomotive.”

Over the years, Edison recruited a stream of remarkable talent. “When I saw this wonderful man, who had no training at all, no advantages, and did it all himself,” recalled a young Serbian inventor employed at the Edison Machine Works in New York City, “I felt mortified that I had squandered my life … ruminating through libraries and reading all sorts of stuff.”

Nikola Tesla didn’t stay for long, and he wasn’t alone. Edison could be trying. He barely ate or slept.

A man should leave the table hungry, he believed, which in his case meant six ounces or less of food per day, washed down by milk. He bathed and shaved irregularly; his suits, stained with chemicals, were clownishly baggy because he feared that tight clothing caused internal bleeding.

Time meant nothing to him. He worked till he dropped from exhaustion, often sleeping on a workbench in his lab.

Almost completely deaf for most of his life (“I haven’t heard a bird sing since I was 12”), he considered his disability an advantage because “it has preserved me from the distractions of a noisy world.” But even deafness couldn’t keep him from rendering harsh judgments about sounds he could barely hear.

When Sergei Rachmaninoff, considered the world’s leading pianist, auditioned for a contract with Edison’s record company, Edison cut him off after three notes. “Who told you you were a piano player?” he sneered. “You’re a pounder.”

Entirely self-made, Edison disdained those who fell on hard times. And the threat of a labour strike brought out the worst in him, which usually meant mass layoffs. Employees “were constantly on the lookout for jobs that paid better and abused them less,” Morris writes of the demoralised work force.

Edison’s least favourite people were union leaders and pompous academics — the sort who’d never solved a technical problem or built anything of value with their hands. Among his few friends was Henry Ford, a farm boy mechanic like himself.

The two saw eye to eye on many things, though Edison dismissed Ford’s all-consuming anti-Semitism as a waste of precious energy. “I do not want to get into any controversy about the English, Irish, Germans or Jews,” he said, “or even Yankees.”

For all his quirks, Morris reminds us, Edison never lost sight of the future. And that, perhaps, is the key takeaway from this elegant, loosely crafted, idiosyncratic book. No inventor did more to nudge the world toward modernity, and few had a better feel for what the next generation of inventors might pursue.

Topping that list was a plea for a greener country — not because Edison was an environmentalist, but because he despised the excess and inefficiency that had come to define American industry and leisure, thanks in no small part to his close chum, Henry Ford.

“This scheme of combustion in order to get power makes me sick to think of — it is so wasteful,” he grumbled. “Sunshine is a form of energy, and the winds and the tides. … There must surely come a time when heat and power will be stored in unlimited quantities in every community, all gathered by natural forces.” He added, in true Edison fashion: “I’ll do the trick myself if someone doesn’t get at it.”—The New York Times.

Comments