Pursuing Marechera’s Edmund

Tanaka Chidora Literature Today

Memory Chirere has an academic article titled Pursuing Garabha”. Now, here is mine titled “Pursuing Marechera’s Edmund”. I like Edmund. I like him so much that I just want to pursue him in 1 000 words. He is a diminutive character that you find in “The House of Hunger” (1978).

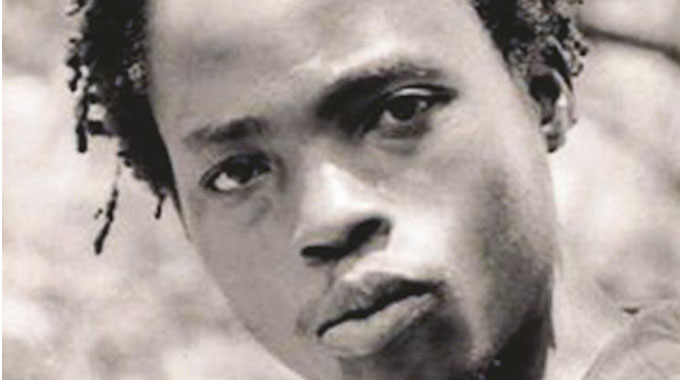

The first time we hear of Edmund in “The House of Hunger” is when he appears in the newspaper as a nameless captured guerrilla. The situation of Edmund is a paradox that makes the protagonist‘s statement, “a cruel sarcasm rules our lives” (p. 60) – an even more poignant one.

After seeing the picture of Edmund, which he initially fails to recognise, the narrator, in one of his characteristic flashbacks, tells us more about Edmund. It turns out that at school, everyone, including the narrator himself, is nasty to Edmund. But there is a dysfunctional relationship between the narrator and Edmund which began when Edmund’s father was poisoned while he was out drinking with the narrator’s father.

Edmund, we are told, likes the narrator, regardless of the fact that he is one of his tormentors. Like the narrator who has a colonially cultivated worship-like affinity for European literature, Edmund is fanatical about Russian literature which leads to a flair for meticulously taking notes of almost every word in the books and has nothing to do with the student armchair politics of his peers.

It is this same diminutive Edmund who challenges Stephen, a typical African bully who speaks all those “isms” of African nationalism – to a fight. Edmund has a mind of his own, a belief in honour and integrity, part of which needs to be gained at all costs by knowing about Dostoevsky and his Russian friends, and another part of which must be gained by challenging anyone who challenges it.

At least that is what constitutes reality for Edmund. But that again is reduced to a stain when he is reduced to a stain by Stephen until he gives up his views of himself and takes up what the Conradian builders of the “House of Hunger” have taught him: “I am a monkey, I am a baboon.” Why then does he go to war? This has been one of those questions that baffle a lot of people. Does Edmund go to war because he believes? But if he believes, why does he die such an unheroic death? His death seems to be the anti-climax of all the hope we might have thought that the novella would impart into us.

One therefore sees that Edmund does not go to war because he believes in this bigger picture contained in the “isms” of revolutions. He desperately wants to believe in himself, to satisfy his hunger for self-assertion. He has been reduced to a stain by Stephen, literally and metaphorically. His beliefs, too.

And when he goes to war in this “House of Hunger”, to fight for ideals that have been reduced to stains (European beliefs have failed to save him from Stephen, but paradoxically, Stephen is the articulator of African nationalism, yet he is a bully), he suffers a fate that is one of the saddest parts of the story.

Musaemura Zimunya (1982: 105) sees Edmund as the archetype of this community of bastards. Like the narrator’s mother, Edmund’s mother is scandalous. Her brazen sexual encounter with Stephen brings as much shame as the narrator gets from his mother’s sexual ministrations to phantoms in the night. This humiliating condition “transcends the biological and becomes a form of perpetual social, economic, political, moral and spiritual dehuman- isation”.

This gives meaning to the hunger. There is a whole lot of ideological poverty and European education has played a very big part. In fact, no matter how articulate the characters are, they still are black stains on the big canvas of white colonialism.

Thus, Peter, the narrator’s brother, knows very well that the problem with his brother is the education he received: “All you did was starve yourself to send this (expletive deleted) to school while Smith made sure that the kind of education he got is exactly what made him like this…” (p. 20).

But where is Peter? He is also acting the role that the system has prescribed for him in the colonial time-space – that of the phallic, archetypal African patriarch who has sex with his woman under the table and beats her to a stain the way Stephen beats Edmund to a stain. All of them are just stains. Even the narrator who can articulate their condition in the form of a novella is just a stain.

But the stains become more frightening when there is an attempt to stitch all the “stainy” pieces back together. Thus, we learn that after some time in the hospital after fighting with Stephen, and after being reduced to a stain, Edmund comes out with a severely disfigured and stitched face: “They wired his jaw. They used a lot of stitches to save something of that crushed-in face. Yards of stitches.

“The term was almost over when he came back to the school. He said nothing; not a word about Stephen. His scarred face had become more pronounced in its moroseness; its particular features seemed to have been stitched together by a fatalistic self-disgust. Smith announced his unilateral declaration of independence. I wrote a short story based on the fight but, as soon as I finished it, tore it up in disgust when I saw Edmund’s stitched-together warthog face” (p. 83).

The violence done to the human body is so enormous that it disfigures the physical features. The violence is so great that the artist tears his artistic expressions of it in disgust. Human suffering is so great that art, instead of expressing it, becomes a mockery of it. However, there is another even deeper dimension to this image of stitches. Edmund is beaten out of identity. His physical features become almost unrecognisable. There is an identity crisis in the “house”.

There is a deeper hunger for identity, as if the individual is asking, “Who am I” Thus, when the narrator undergoes a linguistic and schizophrenic experience, he is expressing this fragmentation of identity. The violence becomes psychological. The hunger becomes soul-hunger and not merely lack of food. The identity of the characters becomes more of a stitched-up thing, just like Edmund‘s face.

Comments