Preferring blindness to deceitful sight

Elliot Ziwira

Elliot Ziwira

Honestly, how would you respond in this materialistic world where everyone is too engrossed in his own schemes to out-manoeuvre someone else to give a hoot to your suffering and desolation; when a vagrant comes up to you and quips, “Where is God?”

Such a conundrum really, that exposes our foible nature!

But would you simply dismiss his miserable dementia and move on to worry about your own lacks?

Conversant as you are in matters of religion, would you tell him where to find God with such conviction that he leaves with a smiling face and you remain with a free and content soul?

Sacrilege!

You may want to scream, but just hold your horses a little while and hearken well to these tidings from “The Parable of the Madman” in the German poet and philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche’s “The Gay Science” (1882).

In this parable, a madman holding a lantern in the bright hours of the morning enters a busy market place and says, “I am looking for God! I am looking for God!”

As most of the people present were atheists they chided him, “Have you lost him then? Did he lose his way like a child? Or is he hiding?

“Is he afraid of us? Has he gone on a voyage? Or emigrated?”

Undeterred, the madman retorts, “I shall tell you. We have killed him!

“You and I.”

Realising how astounded they looked he dared them further, “God is dead. God remains dead.

“And we have killed him. Yet his shadow still looms. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?

“What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us?

“Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?”

Breaking the lantern on the ground and leaving his audience in a puzzled stupor, he headed for churches and poured out the same theatrical repertoire. Here though he was received warmly, calmed down and taken outside where he continued to rave, “What after all are these churches now if they are not the tombs and sepulchres of God?”

Friedrich Nietzsche’s “The Parable of the Madman” explores the inadequacies of Man, his quest for power and deification; the vices, follies and voyeur inherent in him which draws excitement from trauma and suffering.

With the death of God, not so much literal but metaphorical, Man becomes his own master in a kingdom devoid of morality, equality, rational order or restrictions.

Religion, which according to Karl Marx “is an opium of the people”, puts checks and balances on rational thought and therefore regulates behaviour, without which humanity is doomed.

But is such a form of escapism necessary in an existentialist and nihilistic world where the glaring disparities between the poor and the rich are debilitating to the soul?

In such a situation can religion not be used to subjugate the poor by offering them a temporary reprieve from their suffering, instead of helping them to improve their lot?

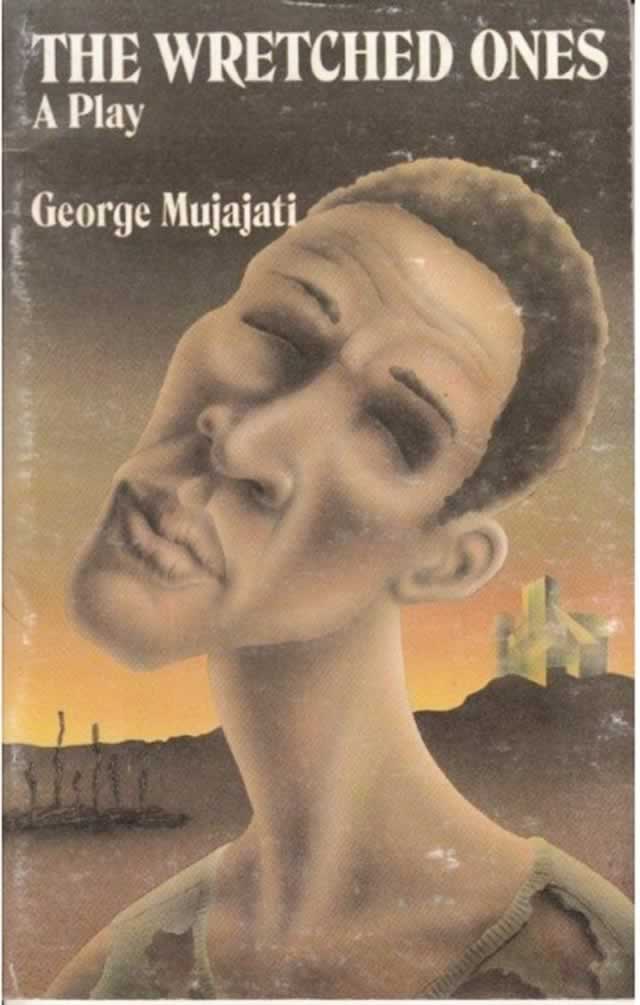

It is against this backdrop that George Mujajati’s play “The Wretched Ones” (1989) is a unique read.

Though a hilarious satire on the surface, the play explores the nature of suffering; desperation, despondency, unemployment and hopelessness in juxtaposition with affluence, individualism, conceit, deceit, cruelty and corruption.

The unequal and tragic nature of life is examined through setting and characterisation as well as style.

Using nihilistic, surrealistic and realistic traits of modernism, the playwright brings to the fore the sordid and mundane existence of the common man who is burdened by abject poverty a stone’s throw away from opulence and abundance. It is the sad story of Lazarus, a Grade Six drop-out who lives with his pregnant wife Patricia and their daughter Liza — his only kith and kin — in a plastic abode in a squatter camp.

The occupants of this camp located in a farm belonging to a businessman, Buffalo, are drawn from the real scum of the earth; people who cannot afford “a piece of bread per day” or “a decent meal per week”.

Lazarus goes job-hunting every day to no avail much to the chagrin of his impatient wife who tells him that, “Looking-for-a-job that is your job! Do you think that you shall find another job other than that one?”

Situations like these where a man’s inadequacies are exposed when he feels that it “is not of (his) own making” creates a desperate and hopeless feeling which robs him of all he thinks he has — his manhood.

The same tag of war prevails in Povo’s Mother’s “household” as she accuses her bed-ridden husband of laziness, and her hungry son of pilferage for helping himself to the only piece of bread in the house.

The miserable occupants of this camp are worn down by poverty in the periphery of an opulent household whose fat cook is deaf to their pleas to spare them bowls of leftovers; preferring instead to throw them into the rubbish bin, pitting them against vicious and marauding dogs.

Mere scare-crows in a flourishing field, the swamp dwellers are reduced to malnourished parasites, stung by hunger and disease.

Such is the nature of life, and their only hope is God. Because poverty “is the big sell-out” as Mashingaidze Gomo reasons in “A Fine Madness”, the hungry squatters resort to Buffalo’s maize crop for survival by taking a cob or two.

Poor Lazarus suffers a double blow as his daughter Liza dies after eating one of the cobs that Buffalo has poisoned to fix them, and he is arrested for stealing two cobs to feed his family. For that offence he is sentenced to pay a fine of $2 or spend 30 days with labour in prison.

Much to the annoyance of the magistrate and the astonishment of the packed courtroom, he is unable to raise the fine. Upon release he learns of his daughter’s demise and his wife’s miscarriage.

As if that were not enough, Buffalo descends on their abode with armed policemen whom he pays to evict them and burn their shacks.

Their hymn to God for divine protection against “the evil one who is planning to destroy us” does not yield any fruits.

Witnessing first hand the fallacy of Moses, the raven’s Sugar Candy Mountain in Orwell’s “Animal Farm” — a utopian place where the down-trodden would converge and rejoice to plenty — he decides that he is done with the deceitful nature of sight.

Like Thomas Edison who refused to have correctional surgery to restore his hearing because he “Would have difficulty re-learning how to channel his thinking in an ever more noisy world”, Lazarus is chided by his wife for closing his eyes and refusing to open them for two days; eventually gorging them with a needle as he “was tired of seeing a world full of riches, luxuries and plenty”.

“For me they do not really exist… They told me lies. They told me lies of sweet things which I will never enjoy.

“They told me lies of a sweet and rich life which will never exist! I would rather see this darkness, because I own nothing more than darkness . . . So I want to see nothing more than this darkness,” he says.

Such is the state of affairs in an existentialistic, nihilistic and surrealistic world where the job-owners who use their financial muscle or chicanery to win tenders and may be referred to as contractors who sub-contract poverty-stricken skilled manpower for a pittance or agencies lambasted in the sub-plot obtaining in Daniel, Buffalo’s son’s play within the play, “1999”, which has prompted the madman in “The Parable of the Madman” (1882) to ask, “Where has God gone?”

Comments