Politics and loyalty

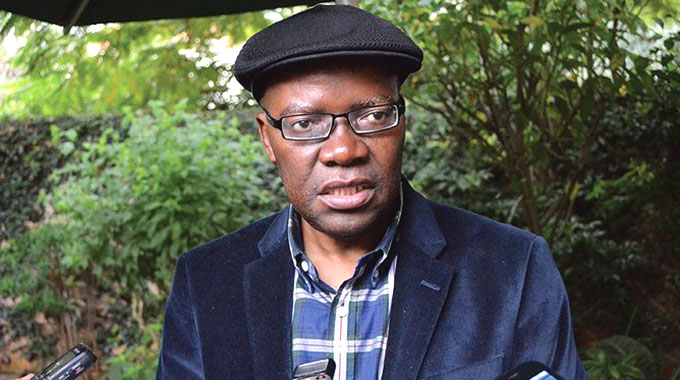

Reason Wafawarova on Thursday

IN political commentary and conversation, the word loyal is quite common, although most of the time it is used as spin. The prosaic, pragmatic, and sometimes pernicious happenings in the gruesome terrain of politics are often given a vague, if not quaint glow, and that is why politicians are normally excellent at putting up public shows. For the past 10 years, the general perception among Zimbabweans was that Dr Joice Mujuru was a loyal deputy to President Mugabe and according to Dr Mujuru herself, that loyalty still exists, even in the wake of her abrupt and dramatic fall from grace. She credits the President with the fatherly role of mentoring her from a 25-year-old semi-literate Cabinet Minister to a doctorate holder, and she argues that with such personal relationship, her loyalty to the veteran politician should not be questioned.

Not long after backstabbing and toppling Kevin Rudd in Australia in 2010, Julia Gillard boldly declared that she had been a loyal deputy to the ousted Prime Minister, shocking many in the process.

She argued that her toppling of the sitting Prime Minister was only done “in the interest of the nation,” and “to get the Government back on track.”

In 44 BC, Julius Caesar was assassinated by fatal stabbing, and the murderous act was an outcome of the scheming of a cabal of 60 conspirators, led by Brutus and Cassius. The assassination took place at a senate meeting on the infamous “Ides of March,” marking the end of the Roman Republic, and the beginning of the Roman Empire, led by the sole power of Octavian, otherwise later known as Augustus.

The jury is still out over Zanu-PF’s decision to terminate the services of key conspirators in the Dr Mujuru faction, who are alleged to have been plotting to topple party leader President Mugabe, failing which they are said to have been contemplating their own version of the Ides of March. The 20 or so conspirators that lost their posts before the Zanu-PF congress were reportedly led by former Vice President Dr Joice Mujuru and Cde Dydimus Mutasa, the axed State Security Minister.

While debate rages on about the goings-on in Zanu-PF, the rhetoric from the former Vice President is quite telling: declared loyalty to the incumbent did not exactly stop the conspiracy for a planned coup, and neither did it quell down wildly burning political ambitions.

Loyalty by its very nature must be an unwavering commitment, not a mere pragmatic alliance with the leader: all centred on selfish personal interests.

The declared loyalty of Dr Mujuru and Mutasa did not exactly shield the incumbent leader against factional blades.

The point here is not that Dr Joice Mujuru and her supporters were inherently disloyal, but that they were probably never loyal to President Mugabe in the first place. In the name of reported moderate reasoning, and perhaps declared loyalty to the party and to the nation, the conspirators were pre-occupied with how best to wrest power into their own hands.

When Dr Mujuru showed promise in 2004, she was in, at the expense of the then odds on favourite, Cde Emmerson Mnangagwa. When she behaved like an out of control charlatan, counter blades turned in her direction, and her perceived support suddenly dwindled to nothingness. Her allies, particularly one Rugare Gumbo, would publicly brag that rival Cde Mnangagwa had now been reduced to “number 13” in the party hierarchy, and that there was virtually nothing stopping their factional don from wrestling power, sidelining or eliminating the incumbent in the process.

A disturbing series of allegations and charges, ranging from incompetence to crass corruption led to the premature dramatic end of Dr Joice Mujuru’s political journey, at least for the time being. If Dr Mujuru is right about her personal loyalty to the President, then that loyalty could not stop her from the misadventure of trying to push aside an incumbent, or at the very least publicly entertaining those instigating her to do so.

We are told that Cde Mnangagwa refused to challenge his temporary collapse in 2004 out of loyalty to both the party and to the party leader. Those close to the recently elevated politician say the man has a thick streak of loyalism to the revolutionary party and to its leader. There is no reason to doubt this. But others argue that the man decided against fighting because he figured out that fighting would be futile, since the incumbent had the numbers, perhaps the same reason Dr Mujuru would not decide to put up any fight today.

Unlike the protagonists in the ever-splitting MDC, Zanu-PF rivals dread the contemplation of splitting the party, although they do not seem to care that much about dividing Government ranks, most the time unfazed by the deadly effect to the service delivery machinery of the state.

Zanu-PF supporters argue that the behaviour of disgraced politicians like Dr Mujuru is not a weakness, but loyalty to the cause for which the revolutionary party stands. However, critics argue that more than loyalty, the pussyfooting politicians are simply desperate, and they cannot imagine a life outside the warmth of the party. In South Africa, the leadership systematically warns would be renegades that “its cold outside the ANC”.

When one looks at how the supporters of Dr Mujuru just watched and waited for fate to take its toll after the scattering of their deck of cards, it becomes clear that what claims absolute fealty is not the leader or an individual, but the party, or is it the permanent vested interests of the players?

The party has an identity above and beyond the individuals who make it up. It has a momentum of its own, which can continue to reproduce itself, despite the divergent trajectories of a few individuals.

Soon after being sworn in as the new Vice President, Cde Mnangagwa explained that the revolution has a way of weeding out malcontents and shaping its own future. Of course he is in the know, given that he has been part of Zanu-PF for over 50 years.

However, the continuity of parties is not that simplistically guaranteed, as the continued MDC splits will show us. But even in the MDC case, the original institution still has a logic that transcends the vast majority of its members, and that is why Tsvangirai’s faction has so far remained the biggest, despite the indisputably blatant shortcomings of the leader himself.

The only reason exposed scandalous church founders and leaders do not normally face the extinction of their institutions is precisely because the church members usually have an irrevocable connect to the logic of the institution, not just blind loyalty to the leader. The congregations of fallen and disgraced church leaders will normally find in the church institution a compelling logic that eclipses whatever feeling of betrayal or shame that may come with the contemptible acts of the fallen leader, especially those that fall to the triumvirate temptation of money, pride, or women.

Generally, political power within parties is wielded and accorded by a select few king-makers.

Loyalty often goes with careerism, and the role of king-makers is to prolong the stay of career politicians.

Like all institutions, political parties reward individuals who exemplify a particular outlook and disposition. For Zanu-PF, patriotism, revolutionarism, and liberation war credentials seem to be the key pillars of the brand, while the MDC barely has a credo, save to say the party has its own sense of right phrases, gestures, slogans, behaviour, ideas, and posturing.

One has, for example, to make resolute claims of being “pro-democracy,” or of being in favour of Western foreign investment as a key policy in itself.

It is those who successfully take up these dispositions that have the most capital in the field, and they end up with power, influence and authority.

While conventional democratic tenets teach us that political competition is free and permeable, and that politicians are answerable to the public; from which they are drawn, practice shows us that professional politicians are often estranged from the general population. They rely not on the voters, but on selected groups and coteries.

Cronyism in politics is hardly counter-intuitive, essentially because political parties reward individuals who successfully perpetuate the culture of the party, regardless of how they carry that out, by hook or crook.

Loyalty becomes the price paid for success, and in its presence vehement ambition can be rewarded unabated. When loyalty becomes questionable, ambition is instantly thwarted, and Nelson Chamisa discovered this reality one fine afternoon at the City Sports Centre in Harare, when he and the majority of Zimbabweans simply could not figure out how he was beaten in an election by the unassuming Douglas Mwonzora. That was a classical role of the king-makers.

It is tempting to conclude that all politicians are heartless mongrels, investing cynically in political parties for their own selfish ends. Any professional entering a new organisation is consciously or unconsciously guided by organisational policy, institutional inertia, and power differences and dynamics. Politicians in political parties are no exception to this rule.

For Zanu-PF, loyalty is simply a promise to help reproduce the institution, in return for the party’s influence and standing. Dr Joice Mujuru is a cadre experienced enough to know that very little can be achieved without the influence and standing of Zanu-PF, and most likely that is why she has already declared that she will “die in Zanu-PF.”

The downside of loyalty is that values and ideas can be sidestepped as leaders sacrifice moral principles for expediency.

There are the undesirable times when party members are supposed to vote with the party, while their moral compasses are pointing elsewhere.

When a politically weak character is in the business of excessive loyalty, often ambition outstrips achievement, and this breeds the culture of mediocrity.

Loyalty is not a virtue above and beyond party membership or ideology, although it is the precondition for success. The endearing faith and constancy required for party survival is often enshrined in continued calls for unbridled loyalty, and we saw increasing calls for loyalty during the just ended Zanu-PF congress. To a political party, loyalty is as much a virtue as it is a vice. It assures party continuity on the one end, and it can be a huge stumbling block to progression on the other.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in Sydney, Australia.

Comments