Pfumvudza, the Zim spring of rebirth

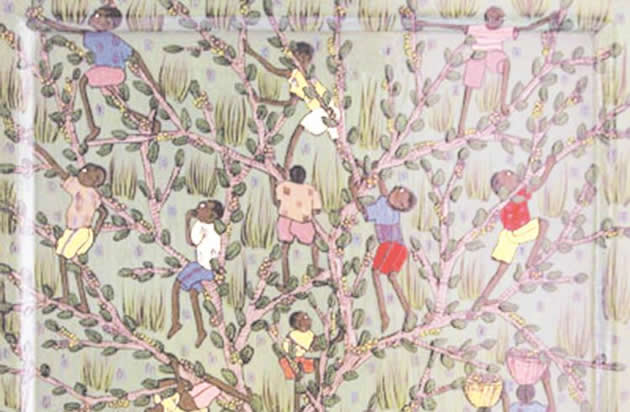

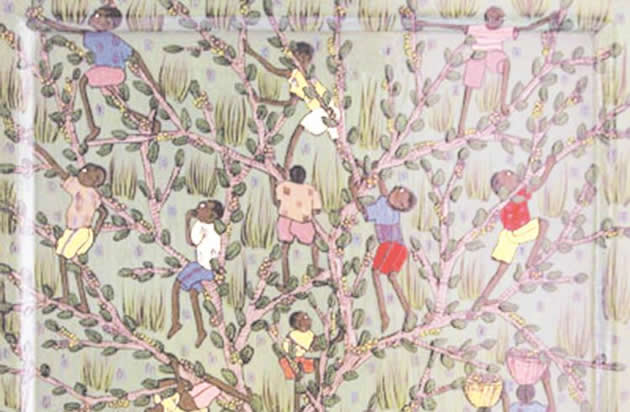

GARDEN OF EDEN . . . The forest is an open orchard for the rural folk and especially the young to pick wild fruit of the dry season

Sekai Nzenza on Wednesday

The lovers stood by the village road side. They were slightly hidden by the new leaves of the spring pfumvudza bushes. She wore a transparent red blouse and you could easily see the cream or perhaps brown lacy brassiere underneath.

Her skirt was flared with blue and red flowers. Her beautifully plaited head was bent down like she was looking at something that she had dropped. Meanwhile, her long slim hands were plucking and pulling the tender red and orange new leaves of the mutondo bush. A few leaves were already littered across the potholed sandy road.

He wore a matching red shirt with the top two buttons open. His jeans were faded at the front and also at the back. His white sneakers had various logos on them. He stood right next to her and stepped back when he saw the car. The boy looked to the left side then to right side with a slight embarrassment. Then kicked the soil gently with his clean white shoe and chewed a piece of grass.

It’s spring time in Zimbabwe. In the west, the big red sun was setting, surrounded by soft colours of red, orange and a slight tint of purple. The haze covered the sun’s setting rays. Within half an hour or a bit more, the sun would be gone and the young lovers will probably embrace, maybe kiss and maybe do something that they are not supposed to do. They say love blossoms around here mostly in the spring, when there is little work to do in the fields.

“Stop the car Tete, stop the car,” my niece Shamiso said. I obeyed the order. She quickly got out and greeted the boy and girl.

Shamiso and I were coming back from another village where we had gone to borrow a couple of clay pots and gourds in preparation for my mother’s kurova guva ceremony, bringing back the ancestor spirit home.

The ceremony had taken a whole month to prepare and by last Friday evening, everything was almost ready, except we were missing a few clay pots to store the seven-day village brew. My cousin, Mai Kiri, suggested we go to her place and pick up the pots from her kitchen hut. Shamiso carefully placed the pots on the floor of the back passenger car seats and she sat in the middle seat, making sure the two pots were sitting well and not moving around. I was therefore driving very slowly along the winding village road when we saw the young lovers.

The young girl was Chiedza, Shamiso’s cousin, from her mother’s side. I had last seen her a few times when she as a baby. Now she had grown up to be a beautiful dark-skinned girl of 18 or maybe 19. The boy, as it turned out, came from a family that had moved to the banks of the Save River few years before.

His family were originally of Malawian origin. They moved to the valley a few years after the white farmer they worked for lost the farm. A friend from the valley said they could get a couple of hectares of land from the village kraal head.

The Malawian family came and settled here, along the river. Although they were not fishermen, they learnt the skill quickly. People said their smoked catfish was the best around here.

“So, what is the name of my babamunini?” Shamiso asked, looking at Chiedza, from top to bottom.

“Caesar,” the boy said, looking rather shy.

“Tete, please close your window so I can tell these young lovers something about the dangers of falling in love in spring, when the new leaves of pfumvudza speak of new life and new love.”

I gently closed the window and let them talk.

Experience is a big teacher. Two years ago Shamiso was just as innocent as Chiedza. Now she is the mother of a baby boy called Prince and she is already separated from her husband Philemon, though I hear that they still get intimate at times, when he comes to give her child maintenance money back in Harare.

I sat in the car and looked up to the Dengedza Mountain and to the rolling bare hills of Mbire towards the east. Everywhere, you could see pfumvudza, the blossoming fresh leaves of our Zimbabwe spring after a spell of rain that came here two weeks ago.

Bumharutsva is what the elders call the rain that comes soon after the cold spell. Sometimes they called it Gukurahundi, the rain that takes away the rusks and empty shells of millet and sorghum after the harvest.

Two weeks ago those rains brought a very cold wind with them. I was here in the village and the sky was gray. Early in the morning, the mist was everywhere. The cold spell was doing its final departure, making way for the heat and the coming of Nyamavhuvhu, month of the wind. After the rains, the trees suddenly came to life, celebrating the new season of heat, waiting for the cicadas to sing louder and ask the rain to come early.

When I see the colours of the pfumvudza, I long for the freedom that it brought when we were young, growing up in the village. This was the season of playing and swimming. There was no hard work to be done in the fields. We were free to roam the mountains, the forests and the hills looking for wild fruits.

At night, while the adults talked to the ancestors during dry season ceremonies, we children played games like chinungu, gwendere gwendere, jejejeje jerekuje, chidhange chidhange, dzwitswi, vasikana iwe, pfukumbwe, zvirahwe, tsoro, mapere, pada, nhodo and many others whose English names we never had.

The forest was an open orchard for us to pick wild fruit of the dry season. And there was plenty of it. We picked nhunguru, matohwe, matamba and hacha. Not too far from the matamba tree near the homestead were several muhacha trees full of the round fruits with hard seed that tasted like nuts inside. You did not climb muhacha because its trunk was thick, with a hard rough bark. We competed with donkeys for the hacha fruit because they too loved it. Hacha, when pounded produced juice that made tasty beer.

We also had a big muzhanje tree in Sekuru Dhikisoni’s field. By the time pfumvudza came, its branches were heavy with the green fruit which would only get ripe in November and December when the rains come.

We wanted mazhanje to ripen quickly so we dug a hole in the ground and stored several unripe mazhanje in the ground to make a pfimbi, or treasure spot. Then we placed a sign so we could remember where the pfimbi was. We used a special thorn twig, a stone or pieces of dry grass. On the fourth or fifth day we came to dig the pfimbi and take out the ripe juicy mazhanje fruits.

This year, mazhanje are in abundance. They say when mazhanje are so plentiful, it means the rains will be scarce. Hopefully, this is all wrong. We wait with hope and anticipation for good rains.

Soon, you will see the burning of grass over the valley and distant fires lighting up in the hills. It is the beginning of warmth and the heat that will be followed by thunder and abundant rain to fill up the rivers. The big catfish will come back in November.

“So, what advice did you give to the young lovers?” I asked Shamiso once she had settled back in the car and was controlling the clay pots in the back seats.

“I told them to enjoy love but also to be aware of the dangers of lust hidden in the spring air. They must exercise caution.”

I nodded, my mind lost to the beauty of a big red sunset sitting on the hills.

Down here in the village, pfumvudza continues to give us the colours of life, the memories of love and forbidden sex among lovers. The young dress up and fall in love. The fresh thick, green and yellow leaves hide their secrets. But the birds sing and see it all. Around our village, they say pregnancy often happens when pfumvudza leaves start to open up from their closed buds.

Springtime in Zimbabwe has not lost its beauty. After the cold season, we watch the colourful abundance of new leaves and the promise of love and a rebirth.

- Dr Sekai Nzenza is a writer and cultural critic.

Comments