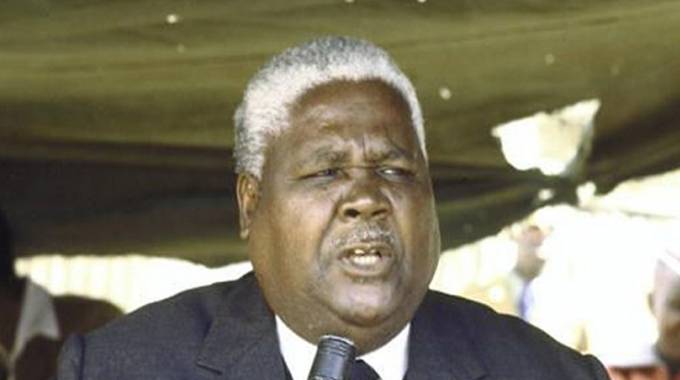

Nkomo’s legacy lives, 21 years on…Father Zimbabwe’s ‘political fashion’ fired up the struggle

Sifelani Tsiko Agric, Environment & Innovations Editor

An avalanche of iconic photographs of Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo, affectionately known as Father Zimbabwe, doning traditional clothing and accessories – “political fashion” in the 1960s — encapsulated the fight against the brutality of colonialism and the Rhodesian apartheid system.

The images that capture Nkomo and his contemporaries’ statement of fashion are among the most influential images of all time in the history of Zimbabwe.

Father Zimbabwe died on July 1, 1999, leaving behind a solid and rich legacy of the nationalist struggle, peace and unity.

As we mark the 21st anniversary of his death, it is important to revisit the life of a revolutionary who had an enduring charisma and stage presence and who was a major source of inspiration for the country’s struggle for independence through the lenses.

Wearing traditional clothing and accessories in the 1960s was largely seen as a symbol of resistance and quest to preserve black African pride. Through it, Nkomo took history in his hands and bent the arc of fashion towards the fight for justice and equality in a subtle, but powerful way.

Nkomo and his contemporaries met various traditional leaders and local communities to garner their support for the nationalistic struggle.

Political fashion of the 1960s offers us some template that tells us of a certain kind of story, a certain kind of process and tools that speak volumes of the nationalist struggle.

Nationalistic images of the 1960s open up spaces to interrogate and understand the legacy of Father Zimbabwe.

In addition, the images help to fill in the gaps in the historical narrative of the nationalistic struggle.

“Fashion and music were used by nationalists to conscientise the general masses on the issues of African heritage and to win their support of the struggle during the liberation war,” wrote Honest Koke and Ushehwedu Kufakurinani, in a history research paper.

The paper titled: “Snapshots from the past: Modernity, Fashion and Lifestyle among the urban Africans in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1960s-1980,” offers some useful insights into the context of archival images of the emergency of the nationalistic struggle.

In many ways, the research work fights against the ‘organised forgetting,’ we see in today’s young generation.

Images with Father Zimbabwe donning traditional gear are quite helpful in our efforts that seek to recover the generation of nationalists that galvanised the masses to tackle the racist Ian Smith regime head on.

Nkomo and his contemporaries were detained and incarcerated for the political beliefs.

“Fashion and music were also mediums of mass nationalism in the first decade of independence. It is important to delineate the cultural trends of the period under review.

“They were, on the one hand, what we call here ‘political fashion’ or and on the other ‘civilian fashion,” wrote Koke and Kufakurinani.

“It was ‘political fashion’ that was used as a medium of spreading nationalism while ‘civilian fashion’ borrowed much from the popular and ‘apolitical’ contemporary fashion moods.

“Political fashion included the wearing of traditional clothing and accessories, military gear or African dress codes borrowed from other African countries.”

The images which are captured in various archival documents do not demean Nkomo and his comrades in the struggle, but strive to document and register dimensions of the struggle and sacrifice they made to liberate the country.

The images illuminate the creative fashion force of Nkomo and his peers as they crafted strategies to fight against colonialism.

“Political leaders had fashions styles that conveyed the nationalist messages of the day shaping and being shaped by popular culture,” Koke and Kufakurinani argue in their paper.

“It is such fashion styles that we refer to as political fashion. By civilian fashion and lifestyles, we refer to everyday styles and dress codes which did not overtly convey political meanings.

“The period under discussion in this paper was experiencing rapid change in both European and African cultures shaped by socio-economic and political trends of the time. Smith had made his Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) of Rhodesia from Britain in 1965, the country was facing sanctions from this declaration, African nationalism was at its height and, finally, the country was torn by war as the Africans sought to liberate themselves from the yoke of colonialism. Fashion, music and lifestyle fed and reflected on these developments shaping trends of the time.”

Through the lenses, we can uncover traces and metaphorical footprints of Nkomo and his comrades in the struggle and how their experiences shaped the stories of their greatness or heroism in the nationalistic struggle.

Images of Nkomo in the 1950s and 1960s are inextricably tied up with the rise of the nationalist movement.

The images weigh on his shoulders and those of his generation as they sought to spearhead the struggle from colonial bondage.

Koke and Kufakurinani note that chiefs and kings, in pre-colonial society wore colourful skins of leopards and skin hats that could distinguish them from their subjects.

This traditional or cultural way of political dressing, they further say, emerged during the liberation struggle and rise of nationalism in colonial Zimbabwe as a way of leaders to communicate their leadership to the masses.

“The two prominent leaders, Mugabe and Nkomo were at the forefront of using traditional dressing for political mileage,” the historians wrote.

“However, it was not common with Mugabe than Nkomo because most of the time Mugabe always wore his suits.

“Others who included Muzenda, Muzorewa, Joyce Mujuru, George Nyandoro and James Chikerema used traditional dressing to support the cause of African National liberation struggle.

“In many rallies and meetings in the 1960s the National Democratic Party addressed rallies wearing African traditional regalia in order to communicate effectively and to appeal much better to the masses. Traditional clothes which the political leaders wore included ngundu (fur hats) dehwe rembada (leopard skins) and also holding tsvimbo (knobkerries).”

Nkomo’s vision for unity, for land equity, social, economic and political rights, can be found by looking not to the future, but to the past in which his visionary and influential political role shaped the country’s nationalistic politics.

Nkomo’s legacy cannot be wished away.

It’s part of us and we walk with it in every Zimbabwean way.

He was Zimbabwe’s foremost nationalist figure who played a critical role in bringing about not only the country’s independence, but national healing and reconciliation among Zimbabweans after the political disturbances of the early 1980s.

His legacy in terms of unity, national healing and reconciliation is still enduring.

Thoughts about his life, his stature, his unifying role, his bold and unyielding fight for land, social, political and economic rights for the majority of blacks should inspire us and the young generation about how his life and sacrifice impacted on our lives.

The name Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo should inspire some reasoning, upliftment and sharing of perspectives about the future discourse of our country’s national politics.

He was a man of the people who taught this nation the importance of unity and the value of the struggle for land in shaping us as a nation.

And no matter the differences that we may hold as a people, it is still very important to preserve Nkomo’s legacy.

The veteran nationalist was born on June 19, 1917 at Semokwe in Kezi District, Matabeleland South.

He was the third born child in a family of eight.

His father Thomas Nyongolo Letswansto Nkomo was a teacher and lay preacher who was trained and worked for the London Missionary Society.

Nkomo was a founding leader of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) and worked with numerous other nationalists in the struggle for the liberation of Zimbabwe.

After primary schooling in Rhodesia, he went to South Africa to complete his education in Natal and Johannesburg. Returning home in 1945, he worked for the Rhodesia Railways and by 1951 had become a leader in the trade union of the black Rhodesian railway workers.

In 1951 he obtained an external BA degree from the University of South Africa, Johannesburg.

Nkomo became increasingly political, and in 1957 he was elected president of the African National Congress (ANC), the leading black nationalist organisation in Rhodesia. When the ANC was banned early in 1959, Nkomo went to England to escape imprisonment.

He returned in 1960 and founded the National Democratic Party (NDP) in 1961, and when the NDP was banned in turn, he founded ZAPU.

The white-minority government of Rhodesia held Nkomo in detention from 1964 until 1974.

After his release he travelled widely in Africa and Europe to promote ZAPU’s goal of black majority rule in Rhodesia.

Nkomo helped lead the guerrilla war against white rule in Rhodesia alongside Robert Mugabe, who headed the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu) after the ouster of Ndabaningi Sithole.

The two groups were joined in an uneasy alliance known as the Patriotic Front after 1976.

When the country gained independence in 1980, there were serious differences between Nkomo and Mugabe which culminated in political disturbances.

After resolving their differences, they agreed in 1987 to merge their respective parties to bring unity and peace in Zimbabwe.

The signing of the Unity Accord on December 22, 1987 led to the end of the civil unrest and brought unity to the country. It was historic.

In 1990, Nkomo became Vice President and played a critical role in shaping the country’s social and economic development.

In 1996, Nkomo was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

His deteriorating health forced him to retreat from public life, although he continued to hold office until his death in 1999.

He died on July 1, 1999, leaving behind a solid and rich legacy of the nationalist struggle, peace and unity.

Comments