Morning comes with mourning

Increasingly, in the ghettos and out there in the villages, we see syndicates of predatory mourners. They can sing and dance all night if the price is right

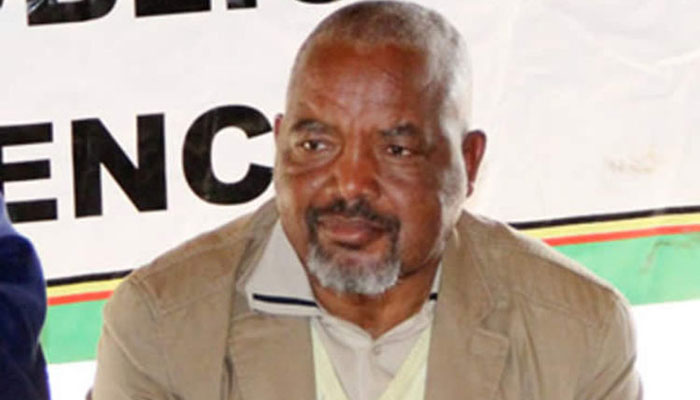

David Mungoshi Shelling the Nuts

There is always something cathartic about mourning. When your flood of tears and emotion wash your eyelids and drench your weeping heart, there is afterwards an unmistakable feeling of having been cleansed. Lord knows we all need some cleansing. There are those who will want to be philosophical about death, saying as one is born, so must they die. True enough, but if that were all, there would just be too much futility to everything in life and we would all be members of the walking dead, awaiting our turn to be dissolved and absorbed by the wormholes of time.

Ecclesiastes 7:2 in the New International Version of the Bible says:

“It is better to go to a house of mourning than to go to a house of feasting, for death is the destiny of everyone; the living should take this to heart.”

While how we mourn is important, it is perhaps even more important to know why we weep and mourn. In a poem called “Nobody Knows Why You Weep” I write:

. . . but honest truth be told

Though you weep like a willow

Nobody knows why you weep

We all know of people who weep very easily, perhaps too easily even, and perhaps because they have too much sympathy and too much empathy in their hearts and must let these spill out like water gushing out of an angry tap. A late brother of mine would weep his heart out whenever he got to any funeral. It was as if he knew every deceased person in more than passing terms. You could tell if he had arrived at a funeral wake just from his wailing and weeping. Even the women, whose lot it is to cry and be disconsolate, marvelled at his ability to weep bitter tears and say painfully bereaved things.

The compliment they paid him was that he cried like a woman. It never occurred to me at the time to ask him why he wept so much for every dead villager. But life goes on and others who weep like him have taken over. Reader, you must have heard about the stranger who got to a funeral and wept in torrents while at the same time throwing himself down and rolling in the dust pitifully.

It was assumed that he was a close relative or a long-lost member of the family even. So those tasked with ensuring that a mourner wept without causing injury to himself leapt to his aid, comforting him as he tore his heart to shreds with the tears of one truly heartbroken. The helpers showed him a safe place to sit and weep from.

It was assumed that he had come from far and must therefore be thirsty and hungry. Food and drink came and soon he was gorging himself on funeral cuisine — plenty of sadza and meat. Not too long after, his hunger and thirst now satiated, he sat with a tooth pick and as he removed bits of beef from between his teeth he was heard to mumble, “Gara zviya mati afa ndiani?” meaning “Forgive me, who did you say is the dead person?”

Perhaps it was this kind of person I had in mind when I wrote:

You are a perpetual mourner

Adrift on the rough seas that life brews

And though you weep in torrents

In truth nobody knows why you weep. What we have in today’s world, and this is not to say that this is something new, is a distinguished brigade of mourners who will always be in the right place at the right time. Like police dogs, they have become very good at sniffing out funeral wakes and attending each as if their very life depended on it.

These people do not return to wherever they will have come from until after every little bit of food and drink is exhausted and only the bereaved few who are family are left. Only then does this person go home for a well-deserved bath and a change of clothes. Increasingly, in the ghettos and out there in the villages, we see syndicates of predatory mourners. They can sing and dance all night if the price is right. All you need to do is make sure there is a plentiful supply of food and drink and the funeral wake for your beloved will be one for the archives — unforgettable! Reader, I am not trying to or intending to contradict the good book.

It is indeed better to be in a house of mourning than to be where the feasting is. Strange things can happen where there is feasting and it is easy to be anti-social in such situations because people tend to be loud, careless and frivolous. By contrast, houses of mourning are sombre and thoughtful, with people celebrating the life of the deceased in the avenues of their private pain. Well, that is the way it should be, but in these days of greater visibility, the boundaries between pleasure and pain have become blurred.

That is why those of us who have become too refined to care are not bothered. We throw a few dollars around and our mourning is done for us by weeping, singing and dancing professionals. You can tell what occupation the deceased was in. At a former good time girl’s funeral, her colleagues from seedy bars and safe houses in the avenues dress for the occasion — provocatively and even scantily — and sing naughty songs to which they dance suggestively. This is their idea of a rousing send-off, something meant to rival the 21-gun salute.

Similarly, when dealers, money changers and armed robbers pass on, those from their fraternity mourn with loud honking horns and lavish displays of ill-gotten wealth. You get to think that perhaps this is just one more excuse for partying. Of course the camera-men and video-makers are indispensable. Some will say they are a necessary evil. Who knows? But my question remains. Why do we weep and what comes to us after the weeping? Let me speak like a mystic: Morning comes with mourning. Yes indeed, it does. After the weeping has died down, we begin to see things more clearly, that is, if we really are weeping. The morning I speak of is the morning that comes with discerning, with understanding. It comes from a mourning that is like meditation.

You do not need to be a yogi master or one trained to walk through solid walls to do this. All that you need is a few stretches of silence undisturbed weeping in the heart and introspective thinking. This truth hit me with the force of a gale or Hurricane Katrina the other day. There I was in our favourite stone-floored second lounge, struggling to come up with epigrammatic sentences, sentences so memorable as to be like proverbs. It was not such a good day that way.

The stuff just wouldn’t happen!

Perhaps I had set my bar too high for the day. Lines like John Milton’s “They also serve who only stand and wait” and Lawino’s lament in Okot p’Bitek’s “Song of Lawino”, in which Lawino ruefully observes, “Who has ever stopped men from wanting women?” are very hard to come by. Such short and to the point utterances are the stuff from which proverbs are made. And they don’t fall from the sky. One needs perseverance and thoughtfulness to concoct them. If you are frivolous and mundane you end up with such bombastic nonsense as “This is a concatenation . . .” in which case some smart Alek will conjure up a few tricks and low and behold, your discombobulation is complete!

As I was saying, I was in my second lounge at my creation table — the place where I dream up things and word-process them endlessly until I have something that resembles works of art or meets the standards of my weekly column. On this day, I was about to give it up and take a walk in the garden, when the lady of the house brought me three slices of ripe yellow pawpaw on china. Our pawpaws are sweet to the taste. You eat one and you feel you could eat a thousand more.

Unwittingly, we grew our first pawpaw tree on a fertile compost heap. And yes, you guessed it. A seed thrown there with bio-degradable rubbish germinated. The plant looked so healthy and promising that we let it be. Two years later, we had our first crop of pawpaws. You did not need to sugar these pawpaws. They were oozing with natural sweetness.

Plant a fruit tree and you enjoy the fruit one day. As the delicious juice hits your palate, you remember with love and fondness, the person who gave the fruit to you. That was how after the demise of my sister Ginny, mourning became morning. She had given me a ripe pawpaw one day, years ago.

- David Mungoshi is a writer and social commentator, a retired teacher and active editor.

Comments