‘Monetary policy must resolve currency conundrum’

Clive Mphambela Own Correspondent

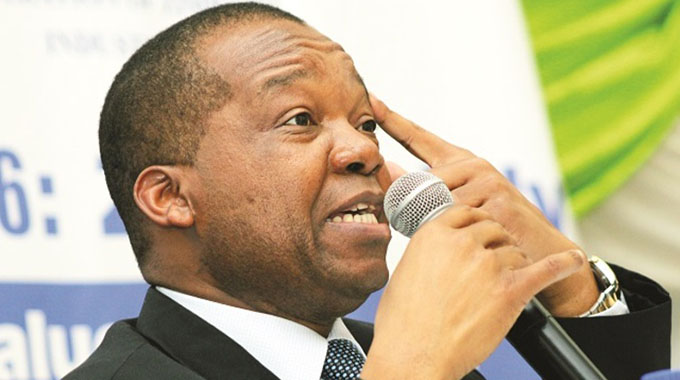

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) Governor Dr John Mangudya is widely expected to release the 2019 monetary policy statement anytime.

In terms of statutes this announcement is already overdue. Notwithstanding the fact that it will be delivered perhaps a fortnight after the monetary policy is due, the country’s central bank chief’s policy position remains highly anticipated against the background of sustained fiscal and monetary related macro-economic fractures in the economy.

There is a heightened debate around currency reforms at the moment and this is one conversation that will not go away by itself.

Not even the RBZ governor or any economist, or layman wish the currency issues bedevilling our economy away.

As public debate rages on, many different schools of thought are coming forth, with disparate and sometimes diametrically opposite views on how the country’s monetary landscape should shape out going forward.

From the extremes, we have those who are clamouring for the return of the Zimbabwe dollar, in one shape or form ie full de-dollarisation. On the other extreme, we have views that say we must first re-dollarise, in other words go back to a proper US$ standard.

Then there are those who are unsure, who want a mixture of the two. Well, from a purely economic standpoint, Zimbabwe has already attempted to de-dollarise.

We have a local currency in circulation in one shape or form, despite us calling it various convenient names. The billions sitting in our bank accounts today are mostly electronic (rtgs) dollars that in any case we mostly earned not via exports, but they have been typed into our computers via electronic money creation, mostly by the Government.

The bond notes in circulation are therefore a representation of this “local currency”, disguised as “greenbacks — $2 bond notes” or “purplebacks —$5 Bond notes”. Some economists have argued that bond notes are not currency, but they are merely a transactional convenience, just the same way electronic balances in our mobile wallets are only useful for transactional convenience, nothing more. But such is the nature of “money”. It is primarily a medium of exchange, before it is anything else.

This means that the Reserve Bank has been and continues to be right in the eyes of many economists, to drive a policy where the economy continues to enjoy the ability to execute transactions, albeit locally.

The major problems, however, come in the fact that in pursuing that policy, some fundamental rules governing money itself have been flouted left right and centre and it is these rules that we must begin to respect, if Zimbabwe’s currency conundrum is to be resolved.

The monetary policy thus is going to be an uphill task. Addressing the deficiencies in the economy requires the RBZ governor to be bold and decisive. Deferring resolution of the currency conundrum to a later date is a luxury the economy can no-longer afford.

Bold but very economically sound proposals are now needed to put finality to the matter. The economy needs clarity and direction on currency.

The currency reform debate is one that is not going to go away and is now in fact a source of added risk to the economy.

There are too many speculative positions being thrown around and that clearly is not healthy.

Cash remains short in the pockets of ordinary consumers, and foreign exchange remains ever scarcer in the hands of importers who have become desperate for foreign exchange to pay for essential inputs.

Following a decade of instability and hyperinflation spanning 1998 to 2008 which resulted in the decimation of financial assets and the eventual demise of the Zimbabwe dollar, Zimbabweans seem quite hung up by and haunted by the wide spread loss of value of deposits and pensions that they suffered during that epoch.

This resulted in the current dearth of confidence in the financial system. Uncertainty as a result of such fears was revived late last year following a spate of price rises in the goods market as well as share prices on the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange, which rekindled feelings of trepidation amongst Zimbabweans and indeed foreign investors.

The direct consequence of foreign exchange shortages on the formal market is that we have a multi tier pricing system in the economy. It is now common place that if one tries to buy a property in the suburbs, a motor vehicle, domestic capital goods or even groceries down town, you can be asked to pay a lower price in US$ cash, a slightly higher price if one is paying in bond notes and an even higher price if one is transacting on electronic platforms. From this entry point, the currency equation requires the government’s immediate attention.

We have to ask ourselves what we are losing as an economy by allowing the “incorrect pricing” of vital resources such as foreign currency.

We get the price distortions that I have already alluded to.

Firstly we have imposed an implicit tax on earners or generators of foreign exchange due to the fixed official peg between local dollars (bond notes) and the real US$ (nostro dollars and USD cash).

Secondly, the value that is supposed to accrue to generators of foreign exchange is accruing in large part to informal currency traders and speculators on the parallel market. Bear in mind a great many importers with genuine foreign currency needs have to meet these needs using the informal currency system. This is not desirable.

Thirdly, there is potential for rent seeking behaviours in the formal markets due to the scarcity factor. Those with privileged access to foreign exchange can and will take advantage of the shortages to enjoy “rents”.

Lastly the shortages have resulted in economic “dead weight loss”. This is the lost economic value (welfare) due to inherent economic inefficiencies accruing to no one in particular.

One of the main reasons why the wheels have rapidly come off as far as bond notes are concerned is that whilst the intentions of the central bank were good and well justified, the introduction of the bond note tended to turn a blind eye on substantial economic fundamentals.

Save for a declaratory note via a directive, which was later supported by legislation, there was no sound economic basis or other credible argument advanced for Bond Notes to be pegged at par with US$.

The central bank simply took a legalistic view. If we say bond notes are one to one with the US$, so be it! Well markets are markets and in the long run (which in this case came very quickly), the market simply found its own equilibrium.

In fact, as soon as bond notes hit the streets, not even the issuing authority itself was able to trade-in its own Bond notes in exchange for US$ on demand.

Value is a creature of the market and cannot be legislated. The legalistic position taken by the central bank was simply erroneous and seemed to assume irrationality on the part of the market. It presupposed by design, that the central bank was smarter than everyone else; and that markets would be incapable of determining the appropriate risk and ascribing the appropriate value to the bond notes.

This article first appeared in our sister publication Business Weekly. The writer is an economist. The views expressed in this article are his personal opinions and should in no way be interpreted to represent the views of any organisations that the writer is associated with. Clive can be reached on +263772206913 and on [email protected]

See full story on www.ebusinessweekly.co.zw

Comments