Machemedze immortalises Chitepo’s legacy

Memory Chirere Correspondent

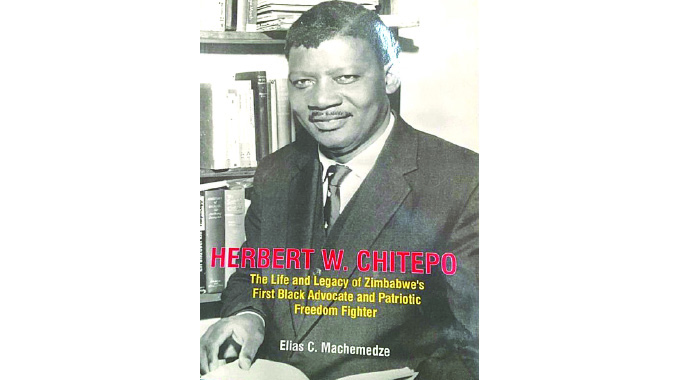

Elias Machemedze, author of the newly-launched book, “The Life and Legacy of Herbert Chitepo”, is almost always referred to as a young writer.

He was born on December 4, 1977, well before Herbert Chitepo’s death on March 18, 1975.

Regardless, Machemedze has put together a book that attempts to recreate the ordinary side of the life of the extraordinary founding ZANU chairman, Herbert Chitepo.

It is the story of a larger than life man retold by an unassuming novelist who has penned works like “Moyo Inzenza”, “Sarawoga” and “Nherera Zvirange” .

Therefore, Machemedze cannot continue to be called a young writer, having immensely succeeded as a novelist, and now moving to research on a man who was instrumental in the founding of modern Zimbabwe.

Many scholarly writings on Herbert Chitepo tend to have a clichéd side to them as they concentrate on the archetypal question: How did Herbert Chitepo die?

While that question is crucial, it usually takes us away from snooping into the road taken by Herbert, the boy from Nyanga.

We rarely go back to the source. Now, the Chitepo story has been pushed beyond the subject of how he died and why?

It has taken another country boy, Elias from Zvomanyanga Hills in Shamva, to unearth the life of another country boy from Nyanga.

The poet of the iconic poem, “Soko Risina Musoro”, has been brought to life by a fellow poet.

This book is not aggressive.

It has a pastoral touch, and reads like a regional novel, which is a story set in a recognisable culture and geography.

It places Chitepo back in the context of the Soko Mukanya totem where he belongs.

It links Chitepo with his warrior magician great grandfather among the Jindwi centuries ago.

Grandfather Chitepo is lured to join Chief Mutasa’s army to bolster the Mutasa people during their wars against Chief Makoni.

Grandfather Chitepo returns home in Nyanga and dies, leaving behind his son, Guwerere, who begets Mufori, who begets Tiyane, who begets Herbert Pfumandini Chitepo.

Tiyane dies and leaves behind Herbert to find his path among all kinds of vultures and saints in his community.

The story is folkloric of course, as it traces Herbert Chitepo through Bonda Mission to St Augustine’s Mission; a poverty-stricken boy who is very good with his school work.

He is not your hero, yet you get to see the rivers he swam in, the mountains he crossed and the songs he sang.

Chitepo later goes to Adam’s College and Fort Hare in South Africa, and comes back to St Augustine’s as a degreed teacher.

Sweet fate sees him being sent by the Anglican Church to the United Kingdom to teach the Shona language to missionaries who intended to come to Southern Rhodesia.

But the Shona teacher is ambidextrous as he ends up studying law at the University of London.

This story follows Chitepo back to Rhodesia, and opens up on exciting issues around his work as Rhodesia’s first black lawyer.

This is an area of Chitepo’s life that many may want to peruse very closely for it is full of surprises.

For instance, Chitepo defended Michael Mawema, the first and interim leader of the National Democratic Party in the Mawema vs the Queen case in 1961 in the High Court of Southern Rhodesia against both conviction and sentence in the Magistrate’s Court on all four counts levelled against him.

With the help of Chitepo, Mawema’s conviction and sentence on the first, second and third counts were set aside, but both conviction and sentence were upheld on the fourth count.

The other sensational and more widely talked about case is when Chitepo appears in the Queen vs Simon Muzenda case, in 1961, where the accused was charged under a section of the Southern Rhodesian Law and Order (Maintenance) Act.

Muzenda was said to have uttered a subversive statement by reciting a passage of a Shona poem “Nehanda Nyakasikana”, which appeared in Solomon Mutsvairo’s book, “Feso”.

The case went through a lengthy trial during which Muzenda’s lawyer, Chitepo, argued that his client could not be accused of breaking the law for reciting a poem which was published and was widely used in schools. At the end of the trial, the accused was only cautioned and discharged.

As a result, Chitepo became popular for the cases in which he defended the nationalist movement in Rhodesia.

He becomes a cult hero.

For that, Julius Nyerere appoints him Tanganyika’s director of Public Prosecutions. Chitepo becomes an internationally renowned lawyer, and an asset to the liberation movements beyond Southern Rhodesia.

However, Chitepo remains central back home in the ANC, ZAPU and latter, ZANU. You learn that the first ZANU Congress in Gwelo in 1964, elects him chairman of the party.

With the emerging of Ian Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence, ZANU nationalists in detention at Sikombela become infuriated.

They declare war on UDI and decide to take real action on the ground.

Therefore, they issue a statement asking Chitepo to establish a war council outside Rhodesia and to immediately launch the war of liberation!

The Sikombela Declaration asks Chitepo not to renew his prosecutor contract in Tanganyika, so that he works full time on the formation and establishment of ZANLA, and start an armed struggle.

That section of the book is revealing on the selfless character of Chitepo as a key builder and architect of ZANLA and Dare ReChimurenga.

Thanks to that, by April 28, 1966, the Chinhoyi Battle occurs.

As to be expected, the book makes its critical contribution to the debate on the death of Chitepo, and how it remains a black spot in the liberation for Zimbabwe up to this day.

However, the life of Chitepo thankfully, overshadows his death in the book.

The book also has rare family pictures from the Chitepo family album, showing the six Chitepo children whom we have only known as adults.

The sweet Chitepo boys and girls look calmly into the camera and you feel like hugging them. You also see the images of a barefooted Chitepo as a schoolboy.

Published by Macheli Press, the book was edited by Professor Ruby Magosvongwe, Eric Mavengere, Molly Nyagura, and Trymore Misi.

It remains a shining example of how young writers could retrieve concrete history and turn it into stories that ordinary people today can easily relate to away from hard politics and history.

Comments