Libraries must adapt

Stanley Mushava Features Correspondent

The library, one of the foremost cultural sites, is ceding its influence to digital technology as visits edge downward in different parts of the world. In Zimbabwe, lukewarm attendance has seen libraries morphing into other ventures such as Internet cafés, and giving up space to unrelated businesses like boutiques. A steep decline in recreational reading, attributed to the increasing penetration of mobile technology, is considered a death-knell to the brick-and-mortar data repository.

Tertiary libraries have held, being indispensable to the business of the mother institutions, but researchers also worry that students’ reading is now mainly exam-oriented.

Another worrying trend is the shortage of local content in many libraries. Stacks are occupied with donated books whose themes have a remote bearing on the Zimbabwean setting.

Government is implicated for backtracking on its commitment to promote the local book sector by buying books for libraries and supporting initiatives like bookmobiles.

The donor alternative is a mixed fortune in that broader exposure concurs with the stunting of the Zimbabwean canon.

Instead of giving up space for unrelated ventures, the library in Zimbabwe can streamline new services which are relevant to emerging needs.

Lupane State University librarian Hlomphang Pangeti said in a recent paper that libraries still have an indispensable role to play as catalysts for community development.

Pangeti observes that libraries must be encouraged as they have an important role in improving community livelihood.

There is an increasing emphasis on communication for development and libraries could be a centre for sustained engagement where non-governmental organisations sometimes carry out relevant but ephemeral campaigns.

“It is ideal to learn from the community and adapt library programmes, services and policies to meet the community’s needs,” Pangeti said.

Pangeti said librarians have strategic proximity with communities which enable them to understand what kind of content people need from the library in order for them to build a satisfying life.

“In every community residents have information needs that should be met by the library. Libraries should be engaged in every activity that the community is engaged in,” Pangeti said.

“The connection between libraries and small-scale economic development must begin with a closer look at the impact of these libraries on their communities in general. Much of the measurable impact has to do with improved literacy practices, the provision of non-formal educational activities, and support of what is often a fledgling reading culture,” she said.

From the writer’s experience of higher education, greater penetration of data gadgetry on campus results in less competition for library resources.

Where previously there would be a scramble for foundation texts, more students become content with finding their way around online resources without bothering with the library except for Internet service and reading space.

Libraries could be short-selling themselves by failing to aggressively push new services which could ensure their relevance.

For example, libraries are conduits for digital content from reputed journals and publishers but such services are still obscure and underutilised.

Quality of research could improve if libraries became a more visible factor of campus life and educate students who are, for the greater part, circulating public domain content.

Public libraries also offer this facility though the traditional conception of the library as physical space stacked with books is still what is prevalent, and waning in popularity.

Higher education could be compromised by lack of exposure to the latest research which could be beyond the spending capacity of students.

“The information landscape of early twenty-first century higher education is characterised by ubiquitous, digitised, indexed online access to content. Researchers and students begin, and often end, their quest for information online,” observes the Council on Library and Information Resources.

“Results of research can be and increasingly are published without traditional publishers or conventional formats. Access to these results, and to the cultural and scientific record that constitutes the primary resource base for research and teaching, is, however, narrowed by the increasingly exclusive use of licensing instead of selling,” CLIR points out.

Libraries keep up with the latest content through subscription but the facility does not seem to be adequately encouraged and utilised.

A 2015 research by Pew Research Centre, which shows a decline in library use in the US, hints at a rethink of services offered by the library while maintaining the traditional role.

The research shows that mobile access to library resources is taking on more prominence in line with technological trends.

“These findings highlight how this is a crossroads moment for libraries. The data paint a complex portrait of disruption and aspiration,” says the report. There is disruption in the sense that new technology is threatening traditional practices and aspiration in the way new ideas are being considered to secure the place of the library in the future.

“There are relatively active constituents who hope libraries will maintain valuable legacy functions such as lending printed books. At the same time, there are those who support the idea that libraries should adapt to a world where more and more information lives in digital form, accessible anytime and anywhere,” the report says.

Suggested roles include supporting community education, serving special constituents such as uniformed forces and immigrants, helping local businesses, job-seekers and those upgrading their work skills, embracing new technologies such as 3-D printers and provide services to help patrons learn about high-tech gadgetry.

This could be useful in Zimbabwe where there has been talk of a declining reading culture but not much deliberation of how reading culture can be revived around areas that are of immediate interest to the public.

Zimbabwe fares exceptionally on literacy in Africa and this could augur well for libraries if they reconfigure their services around the needs of the day.

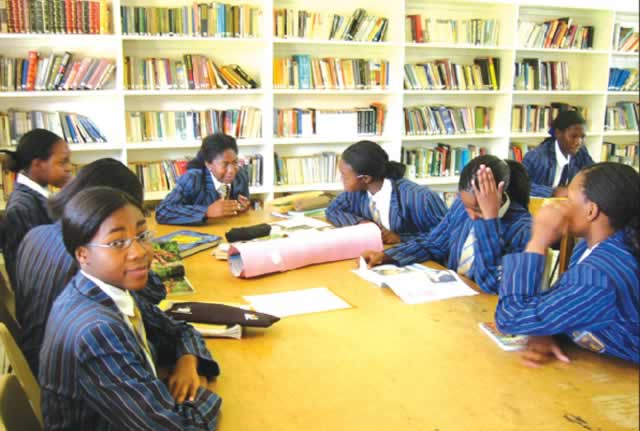

For school libraries, basic education is poorer for lack of content. Great Zimbabwe University scholar Dr Godwin Makaudze faults an exam-oriented reading as the major detriment to Zimbabwe’s reading culture.

“Pupils are only exposed to books that are in their syllabus, and to them, reading only means reading that which is in the education syllabus in order for one to pass,” Makaudze said in a 2015 paper for the Zimbabwe International Book Fair (ZIBF).

“They know no other reading outside the prescribed texts in schools. As a result, when a pupil holds a book the fundamental questions he or she asks himself is whether it is in the school syllabus. If not, then it is not worth spending time on. For many, there seems to be no incentive in reading for leisure,” he said.

Makaudze visited schools around Masvingo in preparation of his paper and observed that some schools cleared literary reads and other textbooks from the library to the storeroom once they were out of the syllabus.

“More to this, teachers in schools, owing to the low budget allocated for books, normally buy the minimum number of set-books that can be studied at each level. In other subjects, only one textbook for the teacher can be bought at a school. Learners then depend on notes given by the teacher,” he said.

If Makaudze’s assessment reflects the broader picture, Zimbabwean education will maintained a sunny impression based on performance in examinations but will not equip students with a wholesome appreciation of the world around them.

Feedback: [email protected]

Comments