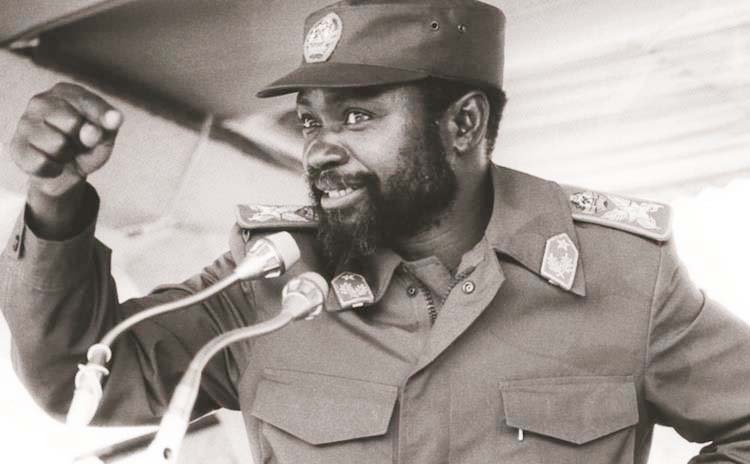

Lest we forget Samora Machel and others

Samora Machel with his Special Assistant Fernando Honwana (right), talking to journalist David Martin in central Manica Province in the mid-1980s. — (Picture courtesy of Sardc)

Phyllis Johnson, Correspondent

On October 20 1986, we woke up to two pieces of alarming news.

The first item was in the local newspaper, The Herald, with a small story at the bottom of the front page saying the wreckage of an unknown plane had been found in South Africa near the border with Swaziland and Mozambique. I alerted my husband, David Martin (now late) about this odd story that brought a deep sense of foreboding, more for what it didn’t say. The 8am news on BBC said President Samora Machel’s plane was missing. He was expected to return to Maputo the previous night from a meeting of Frontline leaders in Zambia, he did not arrive and there was no information.

David and I stared at each other for a moment and then he went into overdrive, working the phone, always the investigative journalist.

He started calling people and people started calling us from various parts of the region and world, asking whether this was true, that the Mozambican President’s plane was missing and wreckage had been found, appealing to us to say it wasn’t true. We had to say that we didn’t know the answer, didn’t want to know it either, but incorrigibly assembling the bits of information that were leading to a heart-stopping conclusion that left us feeling weak.

All of the past decade there had been stories from time to time on SABC, the South African broadcaster, that President Samora had been assassinated or was dead or missing, which was wishful thinking by the South African authorities, who had him in their sights as a key supporter of the African National Congress (ANC) and implacable opponent of apartheid.

South Africa and Namibia were not yet free in 1986.

These reports were never true, and although we grew accustomed to ignoring such disinformation, it always brought a flutter of doubt, that sometime it would happen like that.

But now, now there were too many pieces and SABC was not the source. David was phoning officials and friends in Maputo, many of whom were not answering or the lines were congested.

This was in the time before cellphones, only landlines, and most people were not sitting at their office desks but were out trying to find out what was happening.

One journalist friend from the national news agency in Maputo advised us to tune to Radio Mozambique, which was playing only music, mainly martial music.

This was confirmation that something was very seriously amiss.

This day and night is seared into my memory, as clear and fresh and painful as if it happened yesterday.

David wept, sobs from the depths of his being, the only time I saw him do that, and it was not the confirmation of the dead that triggered this, it was receipt of the list of survivors, which he got by phone and wrote down with a pencil, name by name, from news agency colleagues who had all agreed to share information as it came in.

The list of survivors did not include President Samora, his assistant Muradali Mamadhussein, UN Ambassador Lobo, the well-known academic Professor Aquino de Bragança or our dear and close friend, Fernando Honwana, a brilliant young man of 34 years who was all things to President Samora — special assistant, translator, bearer of sensitive messages and information.

David was holding his breath so tight that he almost wasn’t breathing as he took down the names, and when he wrote the last one and replaced the telephone, he broke down.

There was nothing more to say, more details didn’t matter, the official announcement of survivors confirmed that the others were gone.

Somehow we made it through the day like that, in a blur, constantly on the phone, sharing disbelief and sorrow with people in Maputo, Dar es Salaam, Harare and elsewhere.

Close friends of ours and of Fernando and Samora arrived in the evening and we shared the great gulf of silence left by this day and the one before it — 19 October 1986.

Shock, numb, a great gaping chasm in the region and the world.

How could we continue without Fernando? And Samora?

My time to crack came a few days later when reality set in as we flew to Maputo in a military transport plane, a Casa that was carrying supplies to the funeral.

When I saw the long straight streets of Maputo from the air, I couldn’t hold it anymore. Those streets looked the same but would never be the same again.

Tears streaming down my face, I couldn’t speak, and the pilot, thinking I was afraid of flying, was very supportive, saying that we would be landing soon.

I didn’t want to get there but didn’t want to not get there either. The joint funeral for the 34 casualties and before that, the leadership of the liberation party Frelimo singing Kanimambo, were deeply etched emotional experiences.

The last time we saw Fernando, he was sitting on the arm of a chair in the lounge of our office in Maputo. He had come to say goodbye to me as I was leaving the next day. I didn’t know it would be the last time he said that. He couldn’t stay long because there was a birthday party of a lot of little boys for his youngest son who was turning four years old. He adored his two boys, Ozi and Dick, but travelled a lot and was often away from them, in the era before cellphones and skype made the world shrink. As usual, he and David were besting each other at colloquial phrases in English language, which Fernando had more than mastered at Swaziland’s Waterford School and then York University in UK.

He owned the Queen’s English, as he owned Portuguese and his own language, Ronga. Both he and David could mimic and discuss in several different English accents.

I returned to Harare, leaving David in Maputo. I learned later that he could have been on that plane, that President Samora had urged him to stay and travel with him to the very important meeting in northern Zambia.

He wanted media coverage of the issues.

David thankfully declined as he had another commitment in Harare, and came straight back, returning just a few days earlier.

The president’s plane had crashed into a hillside at Mbuzini in South Africa, near the border with Mozambique, almost certainly lured off course by a false beacon placed in a truck or nearby airport.

All circumstantial evidence points to that conclusion, and there is plenty.

In addition to studying all the documents and transcripts, David and I were invited to travel with the Mozambican team to Zurich for the opening of the aircraft’s black box.

The pilots, captured on the aircraft recorder, complained that they couldn’t see the lights of Maputo Airport, but they were not flying in that direction. The equipment had locked onto another beacon.

Although the South African inquiry blamed everyone else including the Russian pilots and the Russian manufacturers of the aircraft, and technicians at Maputo Airport, another plane flying into Maputo from Beira at around the same time noticed the pull of its instruments in another direction but already had sight of the city.

The South African military were camped nearby to Mbuzini and were on the site before anyone else.

In addition to the removal of President Samora as a benefactor of the ANC under the leadership of Oliver Tambo, who was escalating the fight against the institutionalised racism that was the apartheid system, the South African authorities wanted the documents from the Frontline meeting to reveal what action Mozambique intended to take against the Renamo rebel movement they sponsored, and against Malawi for hosting them.

President Samora planned to set up a military headquarters at Quelimane in north-central Mozambique under his own command, as a former guerrilla commander during the liberation war. He held the rank of Marshall and used this to effect when he was forced by circumstance to negotiate with apartheid South Africa in 1984, when the defence minister General Magnus Malan had to salute him. In that meeting, he described the atrocities being committed by Renamo, cutting off lips and ears, as well as rape, torture and murder. “Are these soldiers?” he demanded of Malan. The general snapped to attention, saluted and replied, “No Sir”.

This incident helps to illustrate Machel’s disarming and personal style. Later, at the White House, he charmed US President Ronald Reagan by calling him “Ronnie” at their first meeting.

Before the meeting was over, the two leaders from different ideological worlds were both on first-name terms. Reagan later sent his daughter Maureen to mobilise support and drought relief during a particularly severe dry spell in southern Mozambique in the early 1980s. Tensions heightened in the weeks before the plane crash and the disinformation circulating in Maputo escalated, just as it had in the weeks before the assassination of Herbert Chitepo in Zambia.

The threats from apartheid South Africa had also escalated, starting October 2, and some commentators wrote at the time that they had decided to overthrow Machel.

On October 6, South Africa warned Machel that he faced a head-on clash with them and that they would “act accordingly”, in response to Mozambique’s support for an increasingly active ANC.

Three days later, they delivered an economic blow by banning the recruitment of Mozambican miners for South African mines.

On October 11, the Mozambican government accused South Africa of planning a “direct attack against the city of Maputo”.

On October 15, Malan threatened military action against the Frontline states, saying they “share the responsibility for the ANC’s acts of terror” and would have to “suffer the consequences”.

On October 16 1986, the Mozambique news agency, published a story saying that “Machel could be one of the chosen targets of the South African military hierarchy”, adding that “Malan’s threats were directed specifically against Samora Machel rather than against Mozambique or its government in general”.

Three days later, Machel was dead, killed in a plane that crashed just inside South African territory.

We had a contact among the few Western diplomats in Swaziland who told us years later that a South African firm had been contracted to renovate the airport at Matsapha at that time and had access to the tower. He was convinced that they had shifted the beacon to give wrong coordinates to pull the plane off course, and he left us with the impression that he knew more than he was telling. He was unavailable for further discussion on the matter, due to orders from headquarters.

President Samora Moises Machel was a great friend of his neighbours Tanzania, South Africa and Zimbabwe, and supported liberation before and after the independence of Mozambique in 1975. He offered full support and a rear base for the liberation war, and he closed his long border with Southern Rhodesia in compliance with UN sanctions, cutting off access to the eastern seaboard. Without his support, and that of Julius Nyerere, Kenneth Kaunda, Seretse Khama, Agostinho Neto and others, South Africa and Zimbabwe could still be fighting that stage of the war for independence. It was a joint effort and many brave and dedicated people paid with their lives. Thirty years have passed. We should never forget.

Phyllis Johnson is a writer and co-author of “The Struggle for Zimbabwe” with David Martin. Some of this information is contained in their book, “Frontline Southern Africa: Destructive Engagement”, published in 1988, which was banned from possession in South Africa until 1994.

Comments