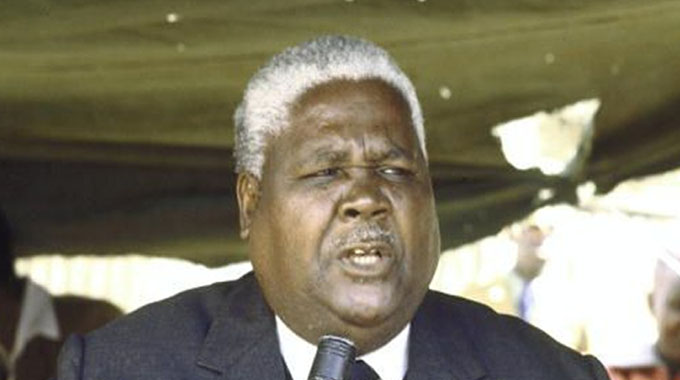

Joshua Nkomo: A globalist, political negotiator, builder

Richard Mahomva

Correspondent

Joshua Nkomo’s legacy is prominently embedded in the military and radical polemic side of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle.

This historiography bias towards Nkomo’s contributions to decolonisation tends to silence his diplomacy and institution-building credentials. In the process, this stifles efforts to memorialise the late Father Zimbabwe for his role as a modern statesman who was ahead of his time. Above all, there has been limited effort to conceptualise Nkomo in the context of his sterling internationalist navigations of power.

As I reflect on Joshua Nkomo’s legacy and his political footprints through the Zapu and Zipra, I also discuss the manifestations of his political negotiation dexterity in Zimbabwean politics.

I also highlight more lessons which can be drawn from his legacy in reinforcing ideas of nation-building and fighting the scourge of neo-colonialism in our national politics.

Zipra as a frontier for diplomacy

After establishing the basis of the first opposition to the Smith regime through ZAPU in 1961, Nkomo established many international frontiers of the armed struggle. As recalled by Retired Col Tshinga Dube (2019: 65) in his biography Russia created the ideological pivot of Zipra:

The philosophy of Marxism-Leninism was glorified as the sturdy foundation of guerrillas’ prolonged conviction in opposing the reactionary as well as rigid representations of oppressively discriminatory scourges like fascism, colonialism, feudalism, racism apartheid and the bourgeoisie hegemonic pillars of governance that were constantly aided the exploitative stereotypically industrialised Western nations. In other words, the ideological facets of class struggles were indispensable to ZAPU’s premise of thought.

Based on this outline of the Zipra ideological premise, Nkomo’s ZAPU transcended the immediate nationalist mandate.

Instead, Nkomo modelled the colonial resistance movement to be ideologically attuned to opposing the global asymmetrical dimensions of power.

During this period, Marxist-Leninist principles were on the battlefront with Western hegemony’s overseas expansionism and post-Second World-War global capital control.

Whilst, Western supremacy was under pressure through Eastern Europe, Nkomo and other African liberation statesman were already motioning the course of decolonisation.

Beyond its conventional military function, Zipra was an agent for nationalist diplomacy. Its agenda linked it with sister-liberation movements across Africa.

In this sense, Zipra had its mandate aligned to the pan-African drive towards ending colonialism.

Moreover, Zipra played a crucial role in integrating Zimbabwe’s demand for freedom in the broader African liberation agenda.

It is from this position that Zimbabwe and the rest of Africa continue to fight for equality in the global political order.

Zimbabwe’s concerted decolonisation efforts were expressed by the military diplomacy links which the Nkomo-led Zipra established with Zambia, Tanzania, Algeria, Angola and South-Africa’s Umkhonto weSizwe.

The African decolonisation frontiers established through Zipra in the fight for Zimbabwe’s liberation give a pragmatic expression to the early inception of what is known to many today as ‘African solutions for African problems’.

Zipra’s alliance with Umkhonto weSizwe reinforced the consolidation of durable cooperation aimed at professional execution of military activity.

This was proved by the outstanding defeat of the Rhodesian Front in the Wankie and Sipolilo Battles. Zambia and Tanzania became Zipra’s strategic partners in providing the human capital for the battles which were successfully fought on the West and East Front.

It was from this military experience that ZPRA produced finest military personnel — most of whom still serve in high ranks of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF).

The current Commander of the ZDF, General Valerio Sibanda is a product of Zipra military training.

As a result, some key institutions of the modern-day state are predicated on the virtues of nationalists like Nkomo.

Joshua Nkomo and political negotiation in Zimbabwe

Needless to emphasise the role of the Geneva Conference right up to the Lancaster House where Nkomo and his then ZANU counterparts were central figures, the Unity Accord of 1987 signed between Nkomo and Robert Mugabe benchmarks the paramount role of nationalist driven political dialogue.

Given the intense political polarisation, what lessons can be derived from Nkomo engagement in political negotiation?

Can we find ground-breaking opportunities for the invention of nationhood against the history conflict experienced in Zimbabwe over the years?

Nkomo’s footprints in Zimbabwean politics provides clear merits of the meaning of national unity. As we anticipate unity and nation-building, dialogue (s) remains a critical pillar for tracing the roots of our homogeneity in the plurality of our conflicting ideological routes.

The sanctity of dialogue in our politics predates the ethos of the new dispensation’s re-engagement trajectory.

Therefore, dialogue is a permanent condition for Zimbabwe’s posterity which emanates from an elaborate past.

Dialogue offers perennial and strategic benchmarks for uniting people from conflict.

To this end, in 1979, the dialogue of moving the nation forward centred on setting the terms and the standards for the independence transition.

In 1987, Zimbabwe recuperated from the fracture of post-independence violence through the Unity Accord initiated by nationalist doyens of the First Republic, Cde Robert Mugabe and Father Zimbabwe, Dr Joshua Nkomo.

Taking a leaf from this experience substantiates how dialogue is a critical condition for establishing defined lines of lasting political interests.

It was the long shared and permanent interests which united ZANU and ZAPU to recovering the idea of a Patriotic Front in 1987.

By 1989 the two political parties held a joint congress ahead of the country’s first Presidential election of 1990.

This was after the expiry of some transitional terms as spelt out in the Lancaster Constitution. This saw executive powers being exerted on the new Office of the President. The coming into effect of the Unity Accord in 1987 and the said 1989 Congress reignited the pre-independence nationalist consciousness which cleansed Zimbabwe from ethnic essentialist politics.

Without doubt, this unity served as a milestone indicator of ZANU-PF’s 1990 election triumph. This is because ZANU-PF epitomised a new sense of national unity which was born out of set terms of a broad-based national dialogue.

In 2008, a local and regionally embedded dialogue gave birth to the Government of National Unity (GNU). Besides the political actors, the key principal interlocutor of the national dialogue was the Organ for National Healing, Reconciliation and Integration (ONHRI).

During this phase of collective and cross-partisan national recovery, wide public consultations by signatory parties of the GNU produced the famous 2013 COPAC Constitution.

Far-reaching points of engagement were made and the rebirth of constitutionalism was realised.

With a united perspective to local solutions for local problems, the Lancaster Constitution was put to rest. That was a noble outcome of dialogue.

Why dialogue now?

At this juncture, all voices of dissent represented by the opposition must be given mutual approbation. No voice must be left out and no voice must usurp a prejudice inclined monopoly in such an important opportunity for Zimbabwe to be in conversation. This should build a long-lasting premise for departing from narrow structural bases of power to the broader apex of democracy.

The decisive national dialogue must be located within the prism of the values of an open society born out of the transitional culture of the new Zimbabwe.

This is where the Political Actors Dialogue comes in!

It is even beyond any reasonable doubt that when Operation Restore Legacy was effected a national conversation of transition was being implemented and symbolically gestured through the civil-military interactions from the 15th of November up to the 18th of the same month.

It would be simplistic to reduce the call for Zimbabwe to be in a self-regeneration conversation to a power crisis management ploy by ZANU-PF.

The prominent articulation of the success of this national dialogue was noted in the manner the people of Zimbabwe defeated the binaries of colour, ethnicity and gender.

Equally, Joshua Nkomo’s legacy is transcendent of the petty political expedience grounded binaries we find our society entrapped in today. As we celebrate Nkomo’s life we must always remember to distinguish our friends from our enemies. This is demonstrated by the alliances which ZAPU and Zipra created with progressive global powers in the execution of the armed struggle. We must continue to seek engagement with political actors giving supports to our struggles. Likewise, we need to invest more in African brotherhood and sisterhood as demonstrated by the links which our armed struggle established in the fight against colonialism.

The templates of the Unity Accord further characterised the Government of National Unity (GNU) should form the basis for our unity against our ever-changing political differences. Above all, we must remain committed to the fight against colonialism.

Richard Runyararo Mahomva is a political-scientist with an avid interest in political theory, liberation memory and architecture of governance in Africa. He is also a creative literature aficionado. Feedback: [email protected].

Comments