Independence was not offered on a silver platter

Elliot Ziwira

At the Bookstore

Independence Day is upon us once again as we celebrate the coming of age of an African ideology and sensibility next Tuesday.

For the 43rd time, our nation takes to the podium to dance to the African tune, imbibe from the African calabash and respond to the heartbeat of the Motherland’s dream.

For more than four decades, the fruits of Independence have been too tasty for some to remember that our freedom from the clutches of imperialism was not an outcome of grandiose and hoity-toity parlance, where one momentarily recovers from a drunken stupor and announces his ‘grand’ arrival on the political, social or cultural scene through keyboard mastery.

Freedom was never a culmination of personal aggrandisement and pomposity coupled with a penchant for the bizarre, where one cries foul when one becomes a target of his own salvoes, and keeps mum if it suits them. Nor was it a result of keyboard heroism—all for ephemeral likes.

There are sons and daughters of an impoverished peasantry who sacrificed limbs, eyes and mental well-being for this beauty of a country formerly known as Southern Rhodesia. And, if they cry for a fair share of the national cake, the tongued ones in our midst label them mercenaries, reminding them that they sacrificed willingly, and should not ask for monetary compensation.

This smacks of callousness and insensitivity.

Such deplorable utterances can only issue from those who did not experience the struggle first-hand.

Zimbabwean literature is a battlefield where individual biographies are pitted against the national one, and to its ethos, especially when it comes to the liberation struggle and its aftermaths.

A perusal of our literary cache will expose the different ways in which the revolutionary zeal and ideology is portrayed.

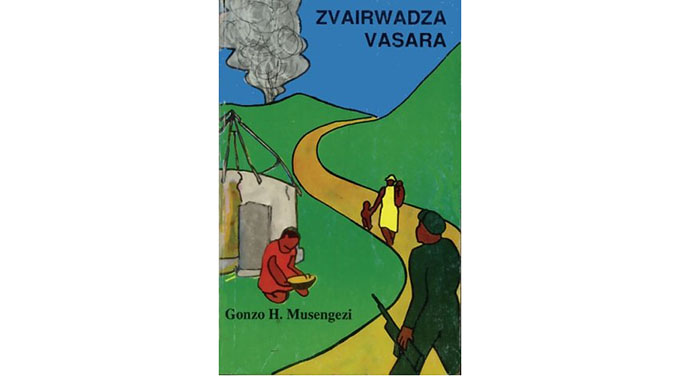

In some instances, particularly in the Shona tradition championed by Vitalis Nyawaranda in “Mutunhu Une Mago” and Gonzo Musengezi in “Zvairwadza Vasara”, the liberation fighters were idolised.

They portray war as glorious and the people who fought in it as formidable, which makes the struggle appear like a stroll in the park.

However, writers in Generation Two, as categorised by Viet –Wild (1993), like Alexander Kanengoni, Freedom Nyamubaya and Thomas Sukutai Bvuma, who were freedom fighters, demystify the notion of the guerrilla as an untouchable genius, who could disappear from the enemy’s canons and author his own epic.

Although the three artists exploit different genres in their depiction of the war of liberation as dehumanising, disillusioning; psychologically and morally degrading, the way they vividly bring the horrendous nuances of the phenomenon to the fore evokes sadness, ire and frustration.

In “Echoing Silences” (1997), Kanengoni, like Nyamubaya in “That special Place” (2003), and Bvuma in “Every Stone That Turns” (1999), uses characters drawn from the war-time and post war-time zones.

But unlike Bvuma, he employs the metaphor of madness and the symbol of ghosts to express his disgust at the phenomenon known as war. Using the protagonist, Munashe, who abandons his university studies for the higher calling, the writer depicts war as dehumanising and deplorable.

In his eyes, war in any context; be it for liberation or otherwise, can never produce victors. Instead, only victims are strewn in its wake, for it “is the greatest scourge of mankind”.

Like others of his ilk, Munashe suffers psychological breakdown during and after the war. The traumatic experiences of the war burden his psyche, which disengages his mental frame.

“Echoing Silences” highlights the profound suffering that the guerrillas face at the architect of both the enemy’s and their own ranks.

The sense of hopelessness pervading the novel is explored through Munashe, Sly, Kudzai, Bazooka and the section commander who was once a teacher.

All the other characters save for Munashe, could not survive the torture, hunger, killings and brutalities.

Kanengoni reasons that Munashe survives probably because he “had died at Chimanda. What survived through the war was (his) ghost”. Like all the others, he is a victim of circumstantial consequences as he finds himself embedded in a labyrinthine snare which he cannot undo. His only vent of escape becomes hallucination through drugs, which reduces his life to a mere reverie.

Throughout the gory war, “the routine killings, the unabated savagery and the dying”, he had always yearned for an opportunity to tell the Section Commander how “disillusioned he had become”

Female combatants like Kudzai, as is also evident in Nyamubaya’s “That Special Place”, are at the mercy of the vagaries of war and the sadistic nature of mankind. Their desires and dreams are set ablaze as some of their fellow comrades, who are supposed to protect them, decide to think in carnal terms. Psychologically unhinged, what is left of them are fragmented souls and empty shells.

Hopelessly reduced to a sex machine by the sex perverts in their midst, Kudzai laments: “Three abortions in one year. My life in the war. What sort of credentials are these?

“I don’t want to be considered anything. I am nobody. I am nothing. . . I no longer menstruate and I am not pregnant. Menopause at twenty”.

Because of the travesty that has become her life, Kudzai yearns for death, and Munashe, who is in love with her, wilts inside. Sadly, or maybe fortunately, she yields to the madness of it all. Thus, to Kudzai, death becomes the elixir from worldly pain.

Another freedom fighter, Bazooka, is followed by “phantom witches that possessed his mind”. Eventually, he dies vainly attempting to escape from the ghosts of his imagination.

Bazooka’s level of disorientation is only equal to Sly’s. Sly believes that he could slip into civilian life easily when he decides that he is “tired of the endless killings . . . tired of everything”, and that he is “not a hero. . . (But) just a poor ordinary person who wants to live”.

This dark side of the war is also depicted in Bvuma’s “Every Stone That Turns”, especially in the poems “Survivors”, “Private Affair” and “Mafaiti-He loved to pluck a plump louse”.

Whereas Kanengoni examines the brutalities of the war, which manifests in psychological chaos and frustration using the metaphor of madness and the motif of ghosts, Bvuma uses crude vulgarity and comic rhetoric to lay bare the dehumanising effect of war.

Bvuma, like Kanengoni, debunks the notion of war as a vehicle that hoists the honey bird to a rich bee-hive by exposing how it creates victims, not only in the combatants, but the families left behind.

In “Private Affair”, Bvuma explores how moral values are thrown to the wind as expressed in the following lines:

We squatted there at dusk a metre apart among the bushes

Emptying our bowels. . .We laughed and choked over steaming shit and assured ourselves that shitting some day become a private affair again.

Like Kanengoni, the poet examines the hardships of war, the hunger and the thirst. Guerrilla fighters deliriously fight over their urine and engage in combat with phantom soldiers.

The level of disorientation during the war deplored by Kanengoni, Bvuma and Nyamubaya reaches a crescendo when the combatants fail to differentiate dreams from reality.

In “Echoing Silences”, Munashe moves about in the rain “opening his palms to try to hold the downpour, behaving as if he were insane”, and Bvuma’s Mafaiti “loved to pick lice from a comrade’s hair.”

These presentations of seemingly trivial actions explore the psychological effects of war at the deeper sense of the bizarre.

Mafaiti cherishes his family and equates his love for his wife and son to his passion for plucking lice. The plucking of lice as a pastime also obtains in Kanengoni’s “Echoing Silences”, as Kudzai and her fellow female combatants are seen “washing their clothes and searching for lice in their wild unkempt hair.”

Bvuma and Kanengoni depict the families left behind as victims, also.

Munashe’s family suffers when he brings the ghosts of war to their doorsteps and subsequently dies; and Mafaiti “fell somewhere at the front”, leaving behind a young family that he so much adored.

Indeed, the heroes, our heroes of the struggle, whose selfless efforts to free the Motherland from the clutches of colonialism, were alive to the fact that freedom could never be offered on a silver platter.

Freedom is not Santa’s gift.

Therefore, they took up arms against a system that created second class citizens out of them. They could not remain caged, for it was not in their nature to be imprisoned birds.

Comments