Gwanda South rural farmers struggle to keep elephants away

Sifelani Tsiko Agric, Environment & Innovations Editor

To tourists and other people in faraway lands, elephants are some of the most beloved and affectionate animals in the world.

But, to Tsepile Nare of Pathana Village in Gwanda South Constituency close to the confluence of Shashe and Tuli rivers on the south-western border with Botswana, elephants are the most resented animals due to frequent crop raids, damage of pipes and water canals at Sebasa Small-scale Irrigation Scheme as well as the terror they bring to the village.

Nare and other villagers have gone to extreme lengths to chase off the elephants.

Villagers living close to the confluence, take turns every night to try and scare elephants away with loud noises, bells, bonfires, revving tractor engines and even by throwing some firecrackers at the jumbos.

“Elephants are a major problem for us here,” Nare says.

“Every night, we take turns to chase them away to protect our crops here at Sebasa Irrigation Scheme. We bang pots, pans, tins, drums to scare them away.

“In extreme cases, we even ask our driver to rev the tractor engines to try and drive them off.”

Says Buhlebenkosi Nyathi, another villager: “We don’t have an electric fence to keep them away. We have a big problem and we need the Government and other NGOs to help us build an electric fence around our irrigation scheme.

“We have reported the matter to the parks people (the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority), but they said they don’t have fuel or vehicles to come and drive away the elephants. At times they come when the crops and irrigation canals have been destroyed. It’s pointless.”

Elephants regularly stray out of the Northern Tuli Game Reserve in the north-eastern corner of Botswana and the south-western part of Zimbabwe, and stampede through villages destroying crops, huts and in extreme cases trampling people to death.

Some of the elephants stray from conservancies on the Zimbabwean side of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, while others are reported to trek from Mapungubwe National Park inside South Africa.

Elephants, a protected wildlife species in Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa, often venture into villages in Gwanda South, mostly at night, to look for food and water at the confluence of Tuli and Shashe rivers, often damaging crops.

Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zambia, which are part of the SADC regional grouping, have the largest concentration of wild elephants in the world.

The big herds, faced with shrinking forest cover and human encroachment of their corridors, venture into human settlements looking for food and attack those who try to stop them.

This has led to the unending human-wildlife conflict among local communities living in areas adjacent to game sanctuaries.

Says Buphilo Nyathi of Mankonkoni Irrigation Scheme: “Elephants are a problem here. When we kill them, we get arrested. When our crops and homes are destroyed by elephants we don’t get any compensation at all.

“We have no interest in poaching these elephants, but when we kill or injure them its in retaliation for crop raids or cattle attacks, or when the parks people don’t come to help us.

“If the Government or parks people allowed us to kill them for meat, we would not have this problem at all.”

The installation of a 99kv solar system plant at Mashaba with support from an EU-funded Sustainable Energy for Rural Communities project (SE4RC) has helped to revive irrigation schemes in Gwanda South constituency, which were facing viability problems due to lack of power.

The project implemented by a consortium of NGOs, with Practical Action as a lead partner is now helping local smallholder farmers at Rustlers’ Gorge, Sebasa and Mankonkoni irrigation schemes to make significant savings on energy costs, while at the same time promoting a cleaner environment.

The mini grid provides power to a radius of 25km, helping to boost activities at the three irrigation schemes, two business centres — Mashaba and Msendami as well as at Mashaba Clinic and Mashaba Primary School.

Gwanda South is a drought-prone region, which receives less than 400mm of rainfall a year. Smallholder farmers here depend on irrigation schemes to survive.

The marauding animals, which also include warthogs, baboons and monkeys, have so far destroyed wheat, maize and bean crops. Sebasa Irrigation Scheme was the worst affected.

The 2018-2019 drought that affected the entire SADC region is forcing the marauding animals to raid crops, threatening the food security position of people in this dry and arid region.

Mlambapele Ward 19 councillor Thomson Makhalima says cases of human-wildlife conflicts were on the rise, sparking fears that people would soon be killed if ZimParks does not help the community immediately.

“Elephants are coming from the Botswana side destroying our irrigated crops.

“These wild animals usually come at night and so far we have received cases from Mankonkoni, Sebasa and Rustlers’ Gorge irrigation schemes,” he says.

“We are appealing to ZimParks to help us now because we are losing our crops to elephants, which attack our irrigation schemes.”

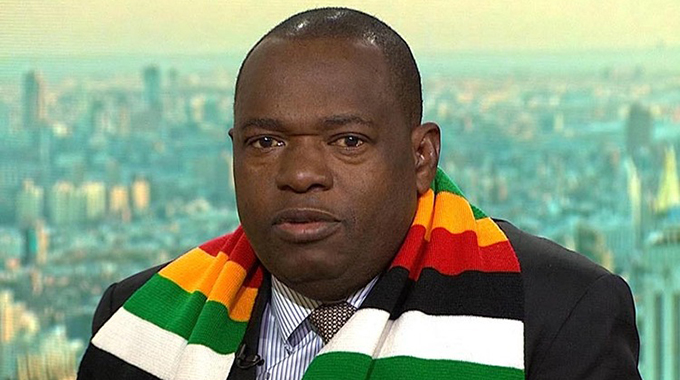

Minister of State for Matabeleland South Provincial Affairs Abedinico Ncube says he will soon discuss the elephant problem with ZimParks officials.

“Elephants are a big problem here and I am going to discuss the matter with ZimParks authorities, so that they can help our communities here,” he says.

“Food security is a key issue for us as Government and we want our irrigation schemes to be productive to help Zimbabwe become self-sufficient in terms of food production. We have to look at how best we can support the farmers to safeguard their crops against the marauding elephants.”

ZimParks spokesperson Tinashe Farawo says his organisation always tries to respond to distress calls from communities despite logistical challenges it faces.

“We always react at the shortest possible time after receiving a report,” he says.

“We encourage communities to report to the authority as soon as possible.”

Elephants have stampeded across various communities in the SADC region, destroying crops, stomping down houses and killing people; forcing people from various communities in the region to go to extreme lengths to deter the jumbos from damaging their property.

In some human-wildlife conflict cases, terrified villagers are often forced to climb onto the roofs of their homes to find a place of safety as elephants roam around.

In an online article written by Emmanuel Koro in May 2019, the environmental writer reported that the human-elephant conflict around the iconic Chobe National Park is now increasingly being felt in Kasane Town where a herd of elephants fatally attacked a 54-year-old local resident, Mr Merafhe Cappie Shamukuni on May 3, 2019.

“Mr Merafhe’s death has put a spotlight on the severe and increasing human-wildlife conflict that communities settled next to national parks of southern African experience daily.

“The herd of elephants killed Mr Shamukuni about 700 metres from his home in Kasane, last week. He was coming from a local township called Plateau where he had spent an evening with friends.”

The burgeoning elephant populations in southern African countries have led to an increase in the human-wildlife conflict, limiting freedom of movement, opportunities for agricultural production, and causing social and economic crises through deaths of loved ones, including breadwinners.

To address some of the problems related to the human-wildlife conflict, SADC passed its Protocol on Wildlife Conservation and Law Enforcement on the August 18,1999 to establish a common framework for conservation and sustainable use of wildlife in the region.

This has largely seen leaders from the regional bloc convening meetings and summits to try and resolve the human-wildlife conflict. About 20 people are killed on average per year due to human-wildlife conflict in Zimbabwe, according to ZimParks.

The wildlife authority says 15 people have already lost their lives in the first half of 2019 due to attacks by wild animals.

In neighbouring Botswana, elephants have killed 36 people in the last few years, with 14 deaths and many more serious injuries recorded since February 2018, according to official reports.

“We don’t have a compensation policy, but we are moving around soliciting for views on how best we can deal with the human-wildlife conflict,” Farawo says.

Many people have sustained injuries of varying degrees across various communities in the SADC region as a result of the human-wildlife conflict.

In 2015, there were 86 recorded cases of elephant attacks on humans in Zimbabwe, while lions killed a combined total of 118 cattle and goats, robbing people of crucial draught power.

The SADC region, faced with this problem, is increasingly coming together to discuss how the region’s natural resources and tourism potential can be better utilised for the benefit of the region.

Heads of State of countries that make up the Kavango-Zambezi (KAZA) Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA) in which the governments of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe are jointly managing some 250 000 elephants, the largest herd in the world, met at the Kasane Elephant Summit in Botswana to try and address the increasing human-elephant conflict in the region.

The Kasane Elephant Summit was held in May 2019 under the theme: “Towards a common vision for the management of our elephants,” and it sought to provide a platform to deliberate on issues and options, including proposing recommendations for management of the region’s elephant population.

The summit further gave updates on elephant populations, the human-elephant conflict, legal and illegal killing for trade in ivory.

The participating countries got input for the development of a framework for international engagement on matters related to elephant conservation and management.

At this summit, it was agreed that there is need to provide public awareness and education on techniques to ensure public safety and reduce human elephant conflict.

Among other things, the Kasane Elephant Summit agreed to develop or review legislation to ensure that revenue generated by tourism benefits those most impacted by human-wildlife conflict.

In June 2019, Zimbabwe hosted the first United Nations and Africa Union Wildlife Economy Summit in the country’s premier resort sport — Victoria Falls.

The summit provided African countries with a platform to share strategies on leveraging wildlife resources to turn around African economies.

For many communities across Zimbabwe and most other SADC countries, the cost of coexisting with wildlife has been huge.

As long as Nare and other people in Gwanda South do not see the tangible benefits that they can get from wildlife resources, it will be difficult to get a positive attitude towards supporting wildlife conservation.

“As long as they receive benefits from wildlife, they will look after it,” says Prof Christopher Magadza, a University of Zimbabwe conservationist and marine biologist.

“The benefits from wildlife resources must address individual and household poverty to help communities support wildlife conservation efforts in the region.

“Building a school, clinic, road and drilling boreholes is not enough, it won’t address individual poverty. Benefits must trickle to the individual level apart from the collective benefits.”

Nare aptly sums up her bitterness: “It’s either the Government chooses people or elephants. And whatever decision they make, we have to survive too.”

Comments