From Rhodesia to Zimbabwe . . . How the war was won (and lost) through music

Elliot Ziwira Senior Writer

When Ian Smith vowed that there would never be majority rule in his lifetime, that of his children and grandchildren (never in a thousand years), he, like most Rhodies, was expressing an illusion — the illusion of Rhodesia.

It was an illusion created by Cecil John Rhodes and his Pioneer Column, who, as Doris Lessing writes in “African Laughter: Four Visits to Zimbabwe” (1992), were on “an adventure for the sake of the Empire, for Cecil Rhodes, whom they knew to be a great man, for the Queen . . .”

They believed that “Salisbury, a white town, British in feel, flavour and habit,” was theirs for keeps because “the conquered were inferior, that white tutelage was to their advantage, that they were bound to be the grateful recipients of superior civilisation” (African Laughter).

What a dream! However, Rhodies lived the dream that Rhodesia was their country, a country begotten on conquest of a “savage” people, bereft of history, culture and customs.

Such is the nature of illusions; they have a way of taking over reality. This was proved true when Smith’s thousand years were reduced to a mere 14 years. With their laager mentality, Rhodesians closed out the indigenes from the milk and honey enclosure of their ancestral land.

They even composed songs to celebrate their invincibility. And to counteract that the African people in their wisdom composed their own songs to give impetus to the struggle for the Motherland.

Same war, different ends

Believing Rhodesia to be theirs for keeps, white Rhodesians cared more for the land and its animals than they did for the real owners of the land — the Africans.

Rhodesia was their country, their land. They would rather protect animals and allow them to roam freely in vast tracts of arable land than give the same land to black people, who were packed in reserves, in what they (whites) derogatory called “kraals”.

Whereas whites were fighting to preserve an illusion, Africans on the other hand were struggling for what was rightfully theirs. They were fighting for equality, against repressive legislation that relegated them to arid lands, robbed them of their humanity, emasculated their sense of worth and usurped their dreams.

To white Rhodesians it was just a bush war, whereas to the people of colour it was a struggle for liberation. They had learnt that violence can only beget violence.

As Fanon (1967) posits: “Colonialism is not a thinking machine nor is it a body endowed with reasoning faculties. It is violence in its natural and absolute state and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.”

He further notes that: “National liberation, national renaissance, the restoration of nationhood to the people, commonwealth: whatever may be the headings used or the new formulas introduced, decolonisation is always a violent phenomenon.”

For Africans, therefore, violence was the only way out, for all else had failed. There was need to fight to the bitter end; to fight for freedom. But since the quest for liberation involves a whole people; to struggle together, collectively, there was need to apprise the people on the reasons for struggling.

Rhodesians had the oppressive machinery in place, and controlled the media, which means by stifling the oppressed people’s sources of information, they determined what they wanted them to hear. Therefore, there was need on the party of revolutionary movements (ZANU and its military wing ZANLA, and ZAPU and ZIPRA, its military wing) to devise means of getting to the people.

They resorted to song.

Same lines, different meanings

Rhodesia became a country through colonisation; a country premised on racism, superiority, plunder, brutality and oppression. It was a country that in all essence belonged to Rhodies.

In that country were two nations; the white nation and the black nation.

White Rhodesians composed songs and popularised them to propagate their view of a white nation, where blacks were considered outsiders. One of such songs was Clem Tholet and Andy Dillon’s “Rhodesians Never Die” which has the following lines:

The story of Rhodesia, a land both fair and great.

On the 11th of November, an independent state.

This was much against the wishes

Of certain governments

Whose leaders tried to break us down

And make us all repent.

CHORUS:

We’re all Rhodesians

And we’ll fight through thick and thin,

We’ll keep our land a free land,

Stop the enemy coming in,

We’ll keep them north of the Zambezi

Till that river’s running dry,

And this mighty land will prosper

For Rhodesians never die.

They can send their men to murder

And shout words of hate,

But the cost of keeping this land free

Will never be too great,

For our men and boys are fighting

For things that they hold dear.

CHORUS:

We’ll preserve this nation

For our children’s children,

Once you’re Rhodesian no other land will do,

We will stand tall in the sunshine

With truth on our side,

And if we’ve to do it alone,

We’ll go alone with pride.

The song ironically and curiously makes two crucial points; that Rhodesia is a whites’ only nation, and that blacks were enemies of that so-called nation. Rhodesia, their nation, became an independent nation-state on November 11, 1965, through Ian Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI).

They portended to keep their “land” “a free land”, from its real owners, whose sons and daughters should be kept “north of the Zambezi.”

Another Rhodie song was “Another Hitler” by Clem Tholet with the lines:

If the world had another Hitler

Then where’d they go this time?

Would they stand aside

And let him roll on through?

Would they keep their smug expressions

Or hide trembling in the dark,

While some little country

Stood and fought for the truth?

CHORUS:

And yet the world attacks my country

For keeping her people free,

With all the young men

That she can find.

There’s 30 000 heroes

Stand to fight the Russian tide:

Will no one come

And fight here by their side?

It was an attempt to keep a receding illusion alive; and it was this illusion that had to be extinguished, through revolutionary songs.

There had to be a way of circumventing censorship and Rhodesian spy networks. United by their quest for liberation, their cultural norms and values as enshrined in their land; the land of their forefathers, black people envisioned a new nation, the nation of Zimbabwe. They knew it existed somewhere in the not so distant horizon of their dreams; what they only required was to be shown the way to that nation.

ZANU Publicity and Information Department deputy secretary Eddison Zvobgo, cited in Julie Frederikse’s “None But Ourselves”, (1990) revealed:

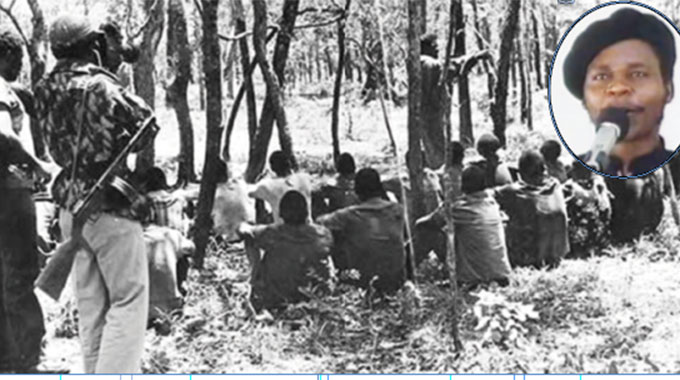

“One of the methods we used very efficiently was the night meeting. We called it pungwe. Pungwe, in Shona it means something that keeps going all through the night.”

ZIPRA political commissar Colin Matutu had this to say: “In ZIPRA we did not call it pungwe; we used the Sindebele word for a discussion, ukwejisa, sometimes.

“The term was different, but we had that exercise of gathering people. We didn’t only talk political theory, for people did not understand all that political jargon. What we had to do, in fact, was to tell them of the hard realities of life” (ibid).

Comrade Zeppelin, ZANLA political commissar, weighed in:

“In fact, overall, the land question was our major political weapon . . .We used to sing songs at pungwes because it helped to boost morale. Traditionally, our people always liked singing, but this singing had some political content to it. Often people would get more from this singing than they did from all the talking. We called them Chimurenga songs” (cited in Frederikse, 1990).

Chimurenga songs played a crucial role in rallying the people behind the struggle. Song, indeed, articulated the nature of collective struggle than did talking. The masses had to be situated in the struggle for their land, enlightened on the reasons for their suffering and the need to distant themselves from the oppressive colonial nation of Rhodesia, which alienated them.

Songs like “Mukoma Nhongo Bereka Sabhu Tiende”, “Nyika Yedu yeZimbabwe”, “Ruzhinji Rwatsidza”, ‘Sendekera Mukoma Chakanyuka” and “Emoyeni Kuyatshisa” captivated and inspired the masses.

Other songs were Cde Chinx’s “Maruza Imi” (You have Lost), Thomas Mapfumo’s “Tumira Vana Kuhondo” (We are sending our children to war), among other Chimurenga songs like “Ndiro Gidi” (Only the Gun), “Muka! Muka! (Arise! Arise!), “Haisi Mhosva yaVaChinamano” (It is not the fault of Chinamano) and “Kugarira Nyika Yavo” (Defending their Land).

Cde Chinx’s composition “Maruza Imi”, speaks to the Empire’s exploitative tendencies, by retracing the colonial route, which dispossessed black people of their land. The song was a morale booster and prophesied victory for the true owners of the land.

Thomas Mapfumo’s “Tumira Vana Kuhondo” responded to Tholet and Dillon’s “Rhodesians Never Die” in a direct way, as translated by Frederikse (1990):

We are sending our children to join the struggle;

Children to war, children to war.

Fathers, mothers, send your children to war,

We are all sending our children to war.

We may be eliminated,

But our children are fighting;

This year we shall send our children to war.

Look, the enemy will be destroyed;

To the war, children!

Children, to the battlefield!

We shall continue to send children to war.

The Chimurenga song, “Kugarira Nyika Yavo” also debunks the notion of Rhodesia, as both a country and a nation, and in its stead maps a new nation of Zimbabwe, born of struggle, collective suffering and resilience. The following lines are apt:

Hark!

It thunders!

Smith! Our brothers and sisters

Are living in the forests,

Because they are protecting our land,

Smith! Our brothers and sisters

Are living in the forests,

Because they are fighting for our country.

They would have wanted

To sleep under a roof,

They would have wanted

To rest,

They would have wanted

To till their lands,

But for the love of our land,

But for the love of our land,

But for the love of our land.

They also want

To have children ,

They also want

To build homes,

They also want

To work,

But for the love of our land,

But for the love of our land,

But for the love of our land.

Yes, it was for the love of our land, that we had to engage in the liberation struggle; it was for the love of our nation that we had to resort to song; and it was, indeed, for the love of our land that many sons and daughters of the soil perished.

Comments