From Rhodesia to Mgagao, from Mgagao to Zimbabwe

Hildegarde Manzvanzvike The Arena

A HISTORICAL narrative littered with contradictions about well-known events is not worth the piece of paper it is written on.

It also leads to fuzzy interpretations.

This is what we are experiencing right now, when the journey from Rhodesia to Mgagao becomes a central point of contradiction, leaving observers wondering why it has to be like this.

Would you blame critics if they say that it might never have happened since there are claims and counter claims?

The contradictions are close to the fights in another revolutionary movement, the African National Congress of South Africa, where terminologies — “white monopoly capital” and “state capture” — are causing more disunity, and you wonder about the futility of the Western-driven mindsets that forget the basics and foundational principles, while chasing meanings from a language that never was theirs, a language that has captured them to such an extent that they cannot focus on how to move the revolution to higher levels that lead to prosperity.

There is no denying that during the liberation struggle, boys and girls, young men and women left the then Rhodesia differently and ended up either in Botswana, Zambia, Tanzania, Ghana, Egypt, Algeria, Mozambique, the former Soviet Union, Romania, Cuba, China and many other friendly nations that supported the struggle.

This is a known fact that cannot be refuted by any sane person. It is also important that the narrative of how they left point A to point B, and finally ended up at point Z should not be questionable because this was not a one-person activity.

Thousands of people were involved, and to date, they can vouch for one another. After interviewing more than 30 war veterans (the pioneers), together with Sunday Mail Deputy Editor Munyaradzi Huni, it became clear to us that once Nehanda’s bones rose, the desire to fight the settler colonialists was unstoppable.

Conducting interviews where the minimum time frame was three hours and the maximum more than 30 hours gave us that rare insight into the pain and pride of Zimbabwe.

We walked with each comrade from the day they left their homestead to go and fight; who they were with; if they were recruited, who the commanders and other freedom fighters were; how they travelled; what it felt like; arrival; training and deployment; return to Zimbabwe, and whether they think that it was worth it to make such a huge sacrifice.

These were war veterans from both Zanla and Zipra, the military wings of Zanu and Zapu respectively. Each war veteran told his or her story freely and many times we had some of them declining to answer certain questions because they were too sensitive.

It was not easy watching almost every one of them (some in their 70s), crying uncontrollably as they narrated some of the most painful events during this journey to Uhuru, a journey where many perished.

Apart from experiencing the war of liberation first hand, those interviews made the writer wonder why just 37 years after Independence, to some the war of liberation is a non-issue, while others reduce it to a walk in the park. Zimbabwe, what is going on?

Well, inasmuch as the years 1975 and 1976 came and passed on, the truth that Mgagao Training Camp in Tanzania existed cannot be wished away, especially the major role it played in shaping the politics in Zanu, through the Zanla forces that trained there.

Just like South Africa and “white monopoly capital”, the squabbles about Vice President Mnangagwa superintending the Government-driven agricultural scheme, the Command Agriculture is taking us back to one of the most sensitive periods of the liberation struggle — Mgagao.

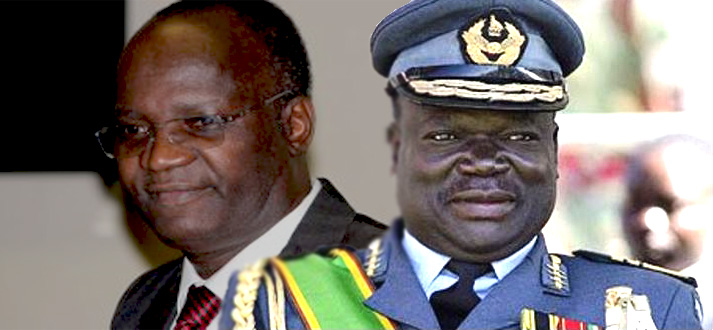

While Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development Minister Professor Jonathan Moyo maintains that he was at Mgagao Training Camp for one day in 1976, Air Force Commander Air Marshall Perrance Shiri, who was also the director of training at the camp told our sister paper The Sunday Mail that that was not possible because there were sensitive events on the ground that had affected the training activities.

He said he was at Mgagao in 1975. Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association leader Cde Christopher Mutsvangwa had also maintained that Prof Moyo was at Mgagao in 1975.

We are not trying to be historical revisionists that rewrite other people’s biographies, but we are just saying that Mgagao was an umbrella under which a number of events that could have derailed the liberation struggle were sheltered, some of which led to the Mgagao Declaration signed by Zanla combatants towards the end of 1975.

It is an open secret that in the Mgagao Declaration, the combatants unequivocally rejected then Zanu leader Ndabaningi Sithole as their leader, and made a number of allegations against him, one of which was that he was receiving funds that he never channelled towards the struggle.

From the interviews the writer alluded to, and also research, these two contentious but significant years (1975 and 1976) can only be understood when we have timelines of events from all the interested stakeholders.

Below are the few I managed to dig out. On March 18, 1975, Zanu Chairman Herbert Wiltshire Chitepo was assassinated in a car bomb in the Zambian capital Lusaka. This led to the arrest of the Zanu leadership by the Zambian government, including the chief of Defence Cde Josiah Magama Tongogara.

Cde Chitepo’s assassination was preceded by the Badza-Nhari rebellion that was sponsored by the Smith regime through the Ken Flower-led Central Intelligence Organisation. It took place towards the end of 1974.

Fay Chung, in her book “Re-living the Second Chimurenga: Memories from the Liberation Struggle in Zimbabwe” gives a personal perspective of how the Chitepo assassination affected the revolution:

“Meanwhile, the freedom fighters held in detention in Zambia or confined to military barracks in Tanzania were becoming increasingly restive.

“The imprisonment of their leaders had not led to the disintegration of Zanla. The different parts of the Zanla forces in Zambia, Tanzania, Mozambique and Rhodesia itself were able to remain united, despite separation by distance, in different countries and the fact that their elected leaders were incarcerated in Zambia.

“It was in this situation that a group of university-educated freedom fighters were able to play a decisive role in keeping Zanu and Zanla united against the settler-colonialist regime of Ian Smith, rather than in suicidal internal wrangling.”

Ndabaningi Sithole had been jailed by the Rhodesians, while the Zanu leadership in detention in Rhodesia had appointed the party’s most senior member and secretary-general Cde RG Mugabe as the new leader. They instructed him to go to Mozambique to lead the struggle.

On April 4, 1975 together with national hero Cde Edgar “Twoboy” Tekere, they crossed into Mozambique accompanied by Chief Rekai Tangwena.

Then on October 15, 1975, another luminary in the struggle Dr Edison Sithole was abducted by Rhodesian forces outside Ambassador Hotel, in the capital Harare and his case remains open.

So, as it were, the Mgagao Declaration signed before the end of 1975, sought to ensure that the struggle continues, but a careful analysis would also show that it scuttled the enemy’s attempts to ensure that Zanla does not continue fighting while they signatories castigated Ndabaningi Sithole alleging that:

(e) He failed to challenge the interpretation of the shooting incident at Mboroma in spite of the fact that he had the full knowledge of what happened. Instead of going to see the victims of the shooting incident in the Zambian hospitals, he decided to fly to America to one of his slightly indisposed daughters because he considered her life to be more valuable than those of the freedom fighters shot at Mboroma.

(f) He told our representatives in Zambia that Chairman Chitepo was murdered by ZANU leaders in prison. We wonder where he got this information. Is he also a Commission of Enquiry member looking into the murder of Chairman Chitepo? If so, why did he unofficially and prematurely disclose his findings to us?

(6). We strongly condemn the cold-blooded-murder of our fellow freedom fighters at Mboroma and subsequent mendacious interpretation of the cause of the massacre given by the Zambian Government . . .”

Responding to Prof Moyo’s claims that he was at Mgagao in June 1976, Air Marshal Shiri said: “Chekutanga, time yaari kutaura, ari kuti June 1976; hakuna reinforcement kana trainee yakauya kuTanzania during that time. Kwanga kusina . . . He mentions two camps that he says were in Tanzania: hakuna macamp akadaro eZanla kuTanzania.”

Meanwhile, 1976 saw the Rhodesian security forces turning the military and refugee camps into killing fields aided by agents like Morrison Nyathi, who had infiltrated the Zanla ranks.

Chung attests to this deep level infiltration saying in her book: “CIO, which had already infiltrated Zanu very thoroughly over the years. Zanu was probably the best infiltrated organisation, with Rhodesian moles in very critical areas, according to Ken Flower, CIO head. The two main ways of infiltrating the liberation movement was through recruits and students. Rhodesian agents, usually young and ambitious . . . ”

If Cde John Gwitira (Kenny Gwindingwi), who was among the people named in the Mgagao Declaration freely gave us a three and quarter hours interview, where he recalled minute details like the registration number of the vehicle that took them from Lusaka to Mgagao, why are these details so difficult to get from Prof Moyo?

Is he privatising history?

Comments