Freeing African minds

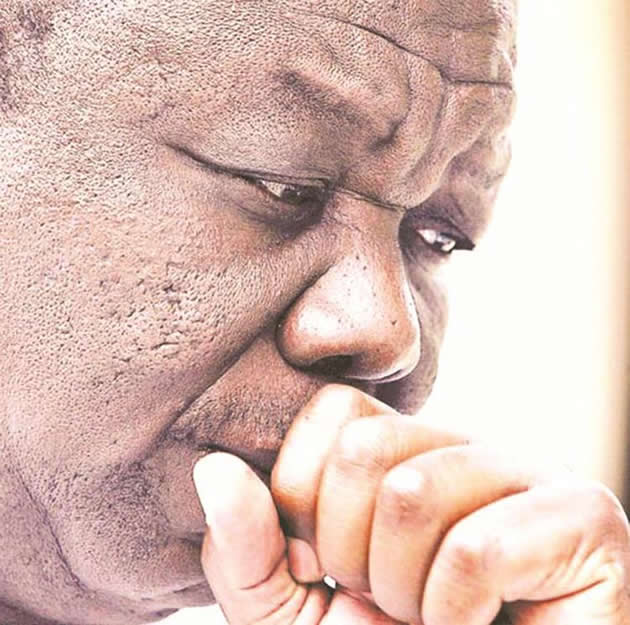

Levi Kabwato Correspondent

While Madonna is being re-embraced by Malawi, Steve Biko is being forgotten in South Africa. These events point to a long trend in Africa’s way of thinking that desperately needs to be reversed if the continent is to escape its subservient role in the global system.

At the end of November 2014, the American pop star Madonna made a surprise visit to Malawi, the first since her public falling out with former president Joyce Banda in April 2013. Back then, Banda had accused Madonna of being “arrogant” and a “bully”, and stripped her of her VVIP status. But now, current president Peter Mutharika took the time to meet with her, restored her status, and appointed her Goodwill Ambassador for Child Welfare.

Madonna’s controversial presence in Malawi began in 2006 when she adopted the first of her two Malawian children and set up the Raising Malawi charity. In establishing the organisation, Madonna explained: “We refuse to turn our backs on those in dire need. Malawians face an unfortunate combination of disease, drought, poverty and a lack of critical resources.”

Malawi was fertile ground for Madonna’s approach. Malawi has typically been more than ready to embrace the narrative of being a country in “dire need” of help. Madonna’s mission hit a snag, however, in April 2013, when she allegedly complained of being forced, on her departure after a visit, to follow the same check-in procedures as ordinary passengers rather than getting VVIP treatment.

Banda responded angrily. “Granted,” she said, “Madonna has adopted two children from Malawi. According to the record, this gesture was humanitarian and of her accord. It, therefore, comes across as strange and depressing that for a humanitarian act, prompted only by her, Madonna wants Malawi to be forever chained to the obligation of gratitude.”

Madonna struck back through Trevor Neilson, head of the Global Philanthropy Group which manages Madonna’s projects, who said: “As the largest private philanthropist to Malawi we would think that the government would be pleased that she is giving her time and money to the country.”

In this public spat, the people who supposedly benefit from Madonna’s acts of charity were reduced to silent bystanders, denied agency and barred from speaking about their conditions, feelings, hopes and dreams. They simply did not exist, were of no consequence and could not, therefore, meaningfully participate in a conversation that could have a significant impact on their lives.

When Madonna “refuses to turn her back on those in dire need” and insists that those she helps can have agency only when expressing gratitude, she reveals how capitalist power works in the global political economy. In Malawi, she speaks and acts within the framework of Western universalism, in which she perceives herself as both a custodian and administrator of “modern” and “progressive” values such as human rights, democracy and good governance. The country she “saves” — not serves — however, is perceived as backward and therefore in “dire need” of urgent intervention which can bring about an end to “the extreme poverty and hardship . . . once and for all.”

She (Madonna) is thus an enunciator and illustrator of missionary exhibitionism in Africa.

For Madonna, to deal with some of Malawi’s problems “once and for all” is a just and legitimate cause which must be pursued regardless of what solutions the owners of the problem, the indigenous people, have and are proposing. In advancing it, she mirrors the proud attitude of Western neoliberal intervention in much of Africa.

Whose language?

Crucially, however, white saviour types such as Madonna do not act alone. They are assisted by a vast and wide network of local actors belonging to well-resourced NGOs, political parties, and other elite groups which receive the bulk of their support from powerful Western donors, multilateral agencies and institutions. These groups have become quite capable of articulating, translating and transferring hegemonic and dominant Western ideas onto the broader citizenry, orienting them towards the preferences and ideologies of global capital in the process. Most NGOs operating in Africa today act as extensions of the dominant structures of the global political economy.

This is not to suggest a lack of agency on the part of African NGO workers, political party activists and other policy elites. But it does seem that through the channels these individuals are exposed to thanks to Western capital — channels such as international conferences, training programmes, policy dialogues and debriefings — hegemonic Western ideas are adopted, translated and then articulated by these African actors. They, in turn, popularise them amongst subaltern groups via workshops, community meetings and the media, helping make dominant Western notions the dominant principles in African countries too.

Through this process, the architecture of global domination is sustained, while the development of alternative ideas, processes and actions which might challenge hegemonic power is prevented. In this regard, it is worth adapting Gayatri Spivak’s question to ask: under the framework of international development, can the subaltern speak?

Could a subaltern demand for a break from aid dependency be heard? Could a redemption song for freedom, emancipation and autonomy be understood by white saviours like Madonna who possess neither the language nor experience of spiritual and material dispossession that is a constant prerequisite of Africa’s participation in a global capitalist system?

Black is beautiful

At the same time that Madonna was being embraced by Mutharika, a controversy was unfolding in South Africa regarding the autopsy documents of the late Bantu Steve Biko, the anti-apartheid activist and founder of the Black Consciousness Movement. The dispute erupted after it emerged that the family which has held the autopsy files since Biko’s death in 1977 intended to auction them off to the highest bidder. The Biko family argued against the sale, and in the end, the High Court suspended the move to give the Biko family more time to make the case that the documents should be returned to them.

This was perhaps a minor victory, but to some observers, the most striking aspect of the whole incident was the relative lack of anger or protest from most South Africans. Far from provoking widespread outrage, one got the impression that the memory of Steve Biko is being forgotten. This is a terrible loss when his ideas are still hugely relevant for understanding Africa’s place in the world and to challenging the ideologies, both amongst Westerners and Africans, that sustain the white saviour industrial complex. After all, it was Biko who warned us that: “The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

It was he who urged Africans to “begin to look upon yourself as a human being”. And it was the founder of Black Consciousness that pointed out that the “logic behind white domination is to prepare the black man for the subservient role.”

Biko’s ideas need to be reignited not forgotten today, when interventions aimed at addressing African problems are more likely to be decided in Brussels, London or Washington than on the continent, and are agreed upon by Western or Western-trained elites rather than the very people who encounter the problems being addressed.

External “assistance” in Africa proved limited in effect, created debilitating forms of aid dependency, and suppressed the creation of organic movements that can aptly respond to struggles of their time. Therefore, the search for a sovereign consciousness, which when found will give birth to new forms of grassroots activism, must begin with a repudiation of existing arrangements of power between Western donors and their NGO handmaidens in the South. Such a refusal would no doubt be met with resistance and punishment in the form of aid withdrawal by the West, if not worse. But that is the essence of the redemptive battle at hand.

We can only sing our redemption song and emancipate ourselves if we deny the white saviour industrial complex its ideological hold on us, and to do this we must collectively rethink our civil society relations and consciousness as Africans. Failure to do so will result in us being continuously “chained to the obligation of gratitude” that Madonna implicitly expects. And it will result in Africans losing possession and control of their histories and memories, even if they reside in the form of something as seemingly unimportant as an autopsy report.

Levi Kabwato is an activist with vast experience in media management, journalism and political science. This article is reproduced from NewAfrican magazine.

Comments