Epworth: The forgotten ‘suburb’

Tichaona Zindoga and Sydney Kawadza Features Writers

The mere mention of Epworth often evokes images of crime, drugs and filth.

Like the biblical Bethlehem, many people think nothing good can come out of Epworth.Okay, some will concede that there is a bright light in the name of comedian-cum-musician Freddy Manjalima, popularly known as Kapfupi.

But one has to give it to the people of Epworth for the enduring human spirit that is evident here as people battle daily adversity as they try to get on with the business of life.

They have personal successes, dreams and hopes, too, like everybody else.

However, there is no denying that the images associated with Epworth, although sometimes exaggerated, are not wholly misplaced.

Located on the periphery of Harare in the east, the township is to all intents and purposes a rudimentary settlement where just about everything – houses, schools, shops – is an improvisation of sorts.

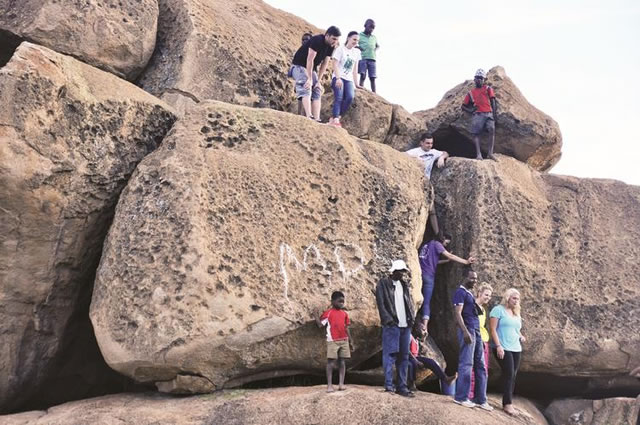

Getting into Epworth via Chiremba Road, the serenity of the famous Balancing Rocks (a national monument) quickly gets snuffed by haphazard, sprawling settlements.

The match-box houses do not seem to conform to any standard and are not serviced with electricity, water and sewage systems while what are called roads are untarred and run-down strips.

Unfazed, resigned or oblivious; people go on with their lives. Making money largely involves selling airtime vouchers, firewood, fruits, vegetables, groundnuts, and maize; and fast foods like fried chips, sausages, basic pastries and so on.

Carpentry and welding, too, are big business.

Shopping centers like Domboramwari, Munyuki, Stop Over, Overspill, Solani, Corner Store and Zimunhu present the kaleidoscope that is Epworth.

“Life is hard here but we survive,” says a woman who identifies herself as Mai Nyasha. She sells sadza at Solani.

Shopping here does not entail baskets and trolleys.

The people live for the day and shopping is calibrated accordingly: measures of maize meal, cooking oil, sugar and meat are sold to order – enough for the day.

“People live from hand-to-mouth here and most cannot afford to buy for the month,” explains a vendor called Tendai. “All that a person needs is to eat now and worry about the next meal later.”

The small measures of daily rations for sale are mostly pegged at US$1 or below.

Such made-to-needs packaging – referred to as “tsaona” – is not unique to Epworth and can be found in high-density areas of Harare and Chitungwiza.

Twelve-year-old Malvern Mazonde and Kimpton Kateya (13) sell samoosas and boiled eggs, respectively.

“This is where my school fees comes from,” Kateya, a Form One student at Epworth High School, tells The Herald on a midweek night as he sells eggs in a bar at Overspill.

The boiled eggs cost R2 each, and Kateya daily brings a handy US$6 to his single mother through his efforts.

Mazonde, who says his mother does not work, makes R30 a day from the R1 samoosas. Needless to say, these are not the kind of samoosas the more affluent order at Indian eateries in Harare’s better suburbs.

Wiseman Table (24) makes a neat sum selling fresh chips and smoked sausages on an Overspill shop front.

He is equipped with a simple electric two-litre deep-fryer and for the past two years it has served him well.

“I make up to US$50 on a good day and on others it is US$40 or US$30. However, I make at least US$20 a day. That is obvious,” he says with no small measure of pride.

He is even an employer, having hired his sister to help in the business.

PaBooster

Table turns out to be a good tour guide – after a couple of pints of lager to convince him, of course.

He says he can find these writers the best ladies of the night that Epworth has to offer, and at “a very reasonable price too”, he reassures. Table knows where mbanje, the most pervasive narcotic, can be found.

The good guide takes us to a place known as “PaBooster”.

During the day PaBooster is an unassuming place conforming to the general template of non-descriptiveness.

A cellphone base station towers over the houses, hence the name of the place.

As dusk falls, the normal daytime activity gives way to scantily dressed women who line road in search of clients.

It is hide-and-seek, as they women scamper to dark corners whenever a police vehicle approaches.

They tell us they prefer that their clients approach on foot so that they can “vet” them from a distance.

Negotiations start as soon as one slows down their walking pace: US$3 for a quickie, US$15 for a whole night’s experience, or whatever you can haggle.

Naturally, it is strictly cash up front.

Alice, a stocky mother of two, says business is good here, and she can afford the US$30 monthly rent from a single weekend’s work.

Alice operates from the house she shares with her daughter; a single room affair that leaves no privacy at all.

“She knows what I do,” Alice claims. “She even goes to the shops to buy (condoms) for me.”

Alice offers us her wares, which we politely decline but are smart enough to leave a tip for her candour in telling us about her work.

According to various accounts, Epworth was established in 1890 as a Methodist Mission station.

The population quickly grew and the Methodist Church handed over the settlement to the Ministry of Local Government in 1983.

Authorities say Epworth was never planned as an urban residential area, hence the lack of amenities.

Little has changed since independence and the people here are expectedly unhappy and residents blame the local authority for failing to bring development.

“They are collecting rates from residents but we have no electricity, we have no roads and we live a life that is almost similar to those in the rural areas,” Norest Chimhuka fumes.

Isabel Chikadare of Overspill adds: “The houses are death traps. There was a year when some of these houses just collapsed because people just build their structures from whatever materials. The local board doesn’t care what kind of houses are built and let out to us. They only want to collect rates.”

Epworth Local Board secretary Kizito Muhomba would not comment when The Herald repeatedly sought an interview with him.

While the local board has done a passable job of maintaining the main roads leading into the various sections of the community, other roads are deplorable.

Residents also feel Government can do more to empower them, especially in helping women.

Crime myths

Crime has always been a major reference point when talking of Epworth.

Residents of the nearby Hatfield, Queensdale and Cranborne suburbs say housebreakers and robbers from Epworth feast on them.

A whole shopping mall in Domboramwari is lying idle, with some Epworth residents saying shopowners felt they made too little money and lost too many goods to theft.

These include a Spar supermarket, a pharmacy and smaller outlets.

“We understand that most shops closed because criminals where shoplifting by day while some broke into the shops during the night stealing anything they could grab. Do you expect the businesses to stay open?

“There are, however, some shops operating and these need to be protected by the authorities from whatever criminal elements bent on taking advantage of the situation,” Denias Batinos says.

ZRP Harare Metropolitan provincial spokesperson Inspector Tadius Chibanda says crimes popularly associated with Epworth are not peculiar to the area.

“Yes, we have received reports of robberies and housebreaking cases from that area but these activities are not only taking place in Epworth but the whole province. People hire taxis, board vehicles seeking transport or use private cars and end up in Epworth.

“We cannot conclude that the criminals are from Epworth but they could be taking advantage that there is no electricity there,” he explains.

Insp Chibanda says like any other place, Epworth has its criminals.

Nonetheless, police regularly hold crime awareness campaigns.

“People should avoid travelling during the night and avoid boarding vehicles without number plates. They should also make sure that they hire taxis that do not have other occupants,” he advises.

“Our officers are firm on the ground and we are reinvigorating our Community Policing Initiative through the neighbourhood watch committees. We also have home officers who share information with people in areas they share and supervise the NWC as we do not have enough resources to cover all areas.”

On prostitution, Insp Chibanda says police carry out raids. Those caught are fined and they immediately return to the streets.

“Prostitution is not confined to Epworth,” he says with a note of weariness, probably tired of answering people who believe Epworth is the worst place on Earth.

Dying for water

However, the main challenge in Epworth is water.

Residents have resorted to sinking wells at their homesteads but these have become a menace with police recording an average of three drownings per week.

“The police have told us to cover our wells and boreholes but we have a serious problem of water. There is no running water in the area and we were relying on the boreholes. We could use the water from the pool for household chores but what do we do for drinking and preparing food?

“We are caught in between a rock and a hard place because water is essential in our lives. Our children risk their lives drawing water from the ‘Pool of Death’,” Brian Chokuda narrates, referring to the former quarry, which derives its name from the scores of lives the pool has claimed over the years .

The “Pool of Death” is a disused quarry that has filled with underground water seeping upwards. Many drownings – several of them suicides – have been reported there over the years. Armed robbers and murderers are believed to also throw bodies of their victims into the water.

Insp Chibanda insists that wells be covered.

“We launched Operation Vharai Mugodhi where all community relations and liaison officers teamed for the campaign in Epworth for the people to cover their boreholes so that we reduce cases of drowning in the area,” he says.

Comments