Editorial Comment: Messing in currency black market does not pay

IT beggars belief that there are still Government suppliers who want to use their payments in local currency for the goods and services they sold, and having passed the tests offered fair value for that they were paid, and then decide to blow it all by playing the black market.

But the Financial Intelligence Unit of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe has found another six companies doing just that, companies that did not seem to get the message in November when 19 companies were blacklisted, that is losing all chance of ever doing business again with Government, local government councils and a range of State-owned entities.

No one is compelled to do business with the Government or other public concerns. But the Government is easily the largest buyer of goods and services, and when you add in all the local government and the State entities the total size of that market is even bigger.

So many companies find it well worthwhile to bid on Government contracts, having been registered with the Procurement Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe and tidied up their tax payments and company returns.

The one hopeful sign, as FIU director-general Mr Oliver Chiperesa noted, is that ever fewer are trying it on, having seen what happens when others take a chance.

But he has caught another six, and is passing on their details to the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development so they can be crossed off the lists of businesses allowed to do business with the State.

What they did was, when they were paid last month, they immediately rushed out and delved into the black market to buy US dollars. These are companies that had, up to that moment, been model suppliers. They passed the tests to be registered by PRAZ as a potential suppliers.

Their bids after tenders were floated proved to be the best. The fairly rigid checks that are done these days showed they were offering value for money, so the Finance Ministry was prepared to make the payments. Then they decide to go off the rails.

There are two other courses they could have followed. If they needed foreign currency fairly quickly to pay some foreign bills they could have gone to the auction.

The Reserve Bank has now eliminated that dreadful backlog dating from a policy that allocated money, which might not have been there, so long as a bid met the rules and had what was seen a reasonable bid price.

These days the Reserve Bank is working differently. Basically bargains are not easy to find and for bidders to be successful they need to bid around the interbank rate, since the Reserve Bank has made it clear that it does not want to see any official dual market rates, the weighted average of successful auction bids and the mid-interbank rate.

The main difference between the two now is not the rates they generate, but what the money is used for.

Interbank sales of foreign currency are mainly for smaller amounts, while the larger sums businesses need are sold through the auction.

The auctions are now more of the bulk suppliers, but with the Reserve Bank making sure that there are no delays, and that the average auction price is very close to the interbank price. This means a serious bidder with approved foreign bills to pay does not need to pay the premium, now fairly modest, in the black market when they can bid a little over the interbank rate, not dramatically so but enough to make sure that even on a quiet day they get their cash. For a start it is still cheaper. Of course they may not have any major foreign bills to pay this month, so want to preserve the value of their payments just in case the monthly inflation rate trips again.

After what we have seen with market manipulations that may not be totally rational, but it is hardly unreasonable. The Reserve Bank offers to sell them gold coins.

The problem of them dipping into the black market is that they help create the very unstable exchange rates that they are trying to hedge against.

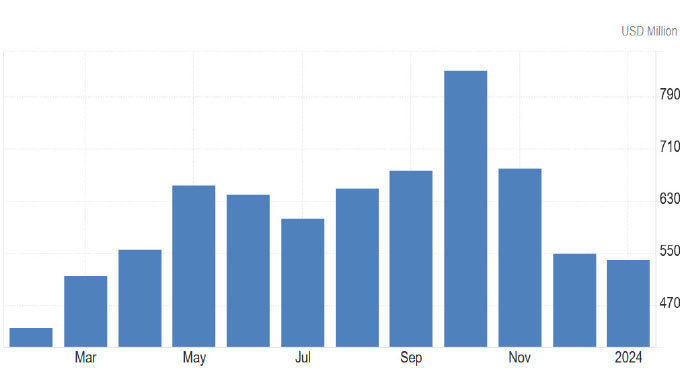

As Permanent Secretary for Finance and Economic Development Mr George Guvamatanga has noted, the black market is far smaller than many people imagine, considering all the hype that goes on in some circles. It handles around 10 percent of the total foreign currency transactions.

This means that even fairly modest extra activity, such as a major Government contractor dumping some cash in that market, has a disproportionate effect. A single brick dropped in a puddle makes a much bigger splash than a truck-load of bricks dropped in a lake.

The other, and unnecessary, foreign currency manipulations come from the five wholesalers that the FIU has discovered are still trying to use black market rates, which they have to potentially guess since there is no agreed-on way these can be found; they are passed around by basically asking illegal dealers how much they pay and how much they charge for foreign currency, and there is variation among dealers.

But the Government and the Reserve Bank have already granted commercial trade coverage against two minor problems.

First there is that gap between the bid rate and ask rate of the banks, down to around 6,6 percent now from highs of over 8 percent, but still significant.

Secondly there are the bank charges of banking foreign exchange, spending it and the like. But commerce is allowed to charge a 10 percent premium on the mid-rate, which covers both sets of potential costs or losses, and brings the “till rate” very close to the black market rate, so customers with foreign currency are happy to pay their retailer or wholesaler, rather than the creepy person on the pavement.

Mr Guvamatanga brought up another point, the fundamentals. Zimbabwe has a net inflow of foreign currency, that is more comes in from all sources than we spend in all outflows, including the black market.

This should make Zimbabwe’s currency stronger every day. The drift down we see appears to have two sources.

First there is the pessimism and the black market manipulations, which the Government is succeeding in chopping back, if not yet eliminating.

The other problem is that we still have walls between our three pools of foreign currency: the retained export earnings in foreign currency accounts, the surrendered export earnings and the free funds, mostly diaspora remittances. These walls are being broken down, but more seems needed so that we have something ever closer to a single pool, which would drive the exchange rate by itself, and with a positive balance of payments, in fact strengthen the local currency.

Meanwhile, while that process is going on, the FIU can at least stop, or strongly discourage, people playing in the black market, and thus distorting that small market which we still find people regarding as the market that supplies the cash to pay the angels in heaven, or at least as something real, rather than just a small side market growing ever smaller that really should have no effect any more on our larger, much larger, main economy.

Comments