Chihlava: Reliving the ‘Legacy of a Sensei’

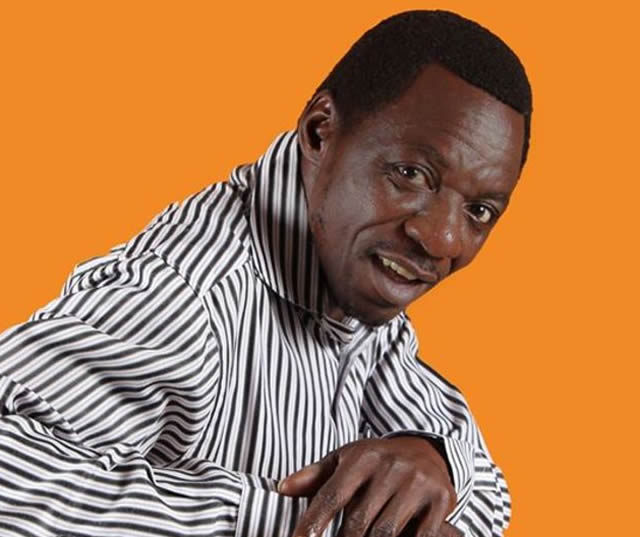

The late Sensei Amos Chihlava

Elliot Ziwira @ the Bookstore

Soke Behzad Ahmadi’s book “Legacy of a Sensei” (1997) explores the transcendental nature of martial arts as a creative discipline that develops a complete man; physical, mental and spiritual, through close scrutiny of the role of a Sensei. He debunks the notion that martial arts, of which karate is one, foist violence in all its forms, but rather contain violence through the subjugation of the raging turmoil inherent in Man.

The writer intimates that: “Real martial arts is mathematics, physics, poetry, meditation in action,” as such the arts transcend individual disciplines.

Ahmadi has written 15 books on martial arts since the 1950s in his quest to take them to the people as a way of creating vents of escape from the violent inclinations of the world. Among his much acclaimed publications are; “Okinawa Grappling Methods” (1956), “Dirty Fighting: Lethal Okinawa Karate” (1959), “Complete Okinawa Karate” (1963), “Okinawa Combat Karate” (1969), “The Karate Seminars: Combative Methods” (1993), “Sensei In Solitary” (2007) and “Legacy of a Sensei” (1997).

CELEBRATING THE LEGACY OF A SENSEI: From right Lloyd Mukucha, Phibion Muzenda (Sensei Amos’ former instructor), Shepherd Ziwira, Gibson Sangweni, Emmanuel Mehlo, Eltone Marongere and Cassidy Chauke

Ahmadi writes: “Karate is to teach a person to handle violence and violent individuals; whether it is tactile, mental or spiritual.” The emotional struggles that weigh down Man converge at a cirque with the mental and spiritual struggles inherent in him, leading to violence. In the struggle for supremacy, mortal Man forgets that the violence that he unleashes on others can always come back to haunt him. Thus, Man’s first enemy is himself. He has to win the battle against himself first before he looks around for enemies; real or imagined.

It is the raging inner man that has to be harnessed first, through the balancing of the mental and the spiritual to create energy, which gives clarity of vision that makes it possible for a small man to win a contest against an opponent of any size, brawn or skill. Indeed, it is not through perfection of technique or skill that one wins his or her battles, but the realisation that enemies and opportunities are not permanent, but problems and conflicts are; and that past loses do not transform to defeats in the same way that past wins are not always victories. Therefore, one has to always look out for the enemy’s momentary lapse in focus, despite his or her otherwise strength in some aspects. Skill and perfection alone are not enough in humanity’s quest to solve its problems.

“A sensei loosely translated means one who has travelled the path prior to us,” (Legacy of a Sensei, 1997), whose experience lends him the wisdom to impart knowledge to others.

As Ahmadi aptly points out: “A sensei’s role is not sorely to transmit the particular knowledge pertaining to a school (ryu-ha), but to guide his students spiritually as well as mentally. A sensei’s path is never ending and through trial, error, shortcomings, victories and defeats, his path affords him with wisdom and enlightenment. In this narration of the life of a sensei, we are once again taken on a journey of laughter, grief, joy and love.”

It is in this vein of examining the role of the competent sensei; torch bearer and teacher that I bleed inside at the death of a legendary teacher, friend, fellow countryman and brother, Sensei Amos Navareth Chihlava. His was a life well lived as he was able to serve his community and country with such diligence that it is only worthwhile for all of us to who have known him over the years, to celebrate his legacy. Sensei Amos, who was a former Zimbabwe Karate Union (ZKU) president, died in the early hours of June 9 2016 at Gweru Provincial Hospital at the age of 57.

According to his daughter Nicole Tsungirirai, the prominent martial artist who had been unwell for some time, was rushed to the Midlands provincial hospital where he was admitted . His condition deteriorated and he succumbed to his illness at 04.43am on Thursday June 9. He was given a befitting send off at Mutapa Cemetery where he was interred on June 11.

Notwithstanding the weather which was always out to scuttle his passion for the sport he loved and lived, Sensei Amos remained resolute, as he went on to serve the Zimbabwe Karate Union as its president, technical director and public relations officer. He was also JKA national chairman. Like what Gene Dunn posits, Sensei Amos was conscious that all his “technique(s) mean(s) nothing” if his “talents” were not used “for the betterment of humanity”.

He was also aware that “most martial artists want to know how a technique is done” and that “a seasoned Sensei will demonstrate why,” (Ahmadi in “Sensei in Solitary” (2007).

An epitome of discipline, hard work, perseverance, fairness and courage Sensei Amos started his karate marathon around 1981 or 1982 which earned him the moniker “Karate Guy” in Gweru. He literally lived, slept and ate Karate, which saw him acquiring a 5th Dan black belt in his chosen style Shotokan, which made him one of the highest ranked practitioners of the discipline not only in Zimbabwe but the world at large.

After using his own resources to shuttle between Gweru and Harare for training sessions and travelling to South Africa for grading, he would come back to impart his knowledge to others at no cost. Such is the nature of a sensei that Ahmadi purveys in “Legacy of a Sensei”.

A record all style Zimbabwe kata and JKA champion, Sensei Amos competed at the Africa Cup in 1994 in South Africa, where he won gold in both kata (imaginary fighting) and kumite (real fighting). As a member of the national karate team between 1991 and 2001, he competed in several Zone 6 (now African Union Sports Commission Region 5) tournaments where he amassed gold and silver medals, becoming the first Zimbabwean to win a Zone 6 gold medal in the men’s kata in 1995.

His crowning moment perchance came in the All Africa Games of 1995 when he was part of the bronze medal winning kata team, becoming along with his teammates Bob Sangweni (late) and Bearn Mavhiya, the only Zimbabwean holders of a medal in karate at the Games to date. His last major tournament was in 1997 at the Africa JKA Championships, where Zimbabwe came second to South Africa in a gruelling final contest that pitted him against the South African Johan La Grange.

Because he believed in the subjugation of the self, before casting aspersions on others, Sensei Amos’ forte was kata (imaginary fighting). Although he could take on any man in kumite (real fighting), he understood that “Martial arts does not teach you how to fight, it teaches you why not to,” (Lakshya Bharadwaj). In spite of his achievements in martial arts, he was never involved in public brawls. His humility, restraint and piety endeared him to all he met, in the ring and outside.

His fellow bronze medalist in the All Africa Games of 1995, Bearn Mavhiya said he was honoured to be associated with Sensei Amos Chihlava, whom he said “excelled through two generations of top JKA karatekas in both kata and kumite.”

My brother Shepherd, who is currently the JKAZ chief instructor and referee and has gone on to produce karatekas of repute including his son Tamuka who became the youngest Shotokan 2nd Dan black belt holder in Africa at the age of14, one of his high flying students said: “Sensei Amos was so passionate about karate. He drank, ate and breathed karate. He was a perfectionist in both kata and kumite. JKA and Zimbabwe karate as a whole will never be the same again”.

The talented Chihlava, who “kicked like a Japanese” impressed the Japanese guru Shihan Masahiko Tanaka (8th Dan black belt) at the 1992 JKA grading in South Africa. But he did not “kick like a Japanese” no, he perfected his kicking techniques to kick like a Sensei.

He perfected his chosen form of martial arts in the same way that Pele, Diego Maradona and Lionel Messi perfected the art of football, regardless of origin.

His other high fliers, Simbarashe Chihlava, Eltone Marongere, David Dube, Frank Muvhakachi (late), Cassidy Chauke and Victor Bhunu, just to mention a few, made Zimbabwe proud in major tournaments across the continent and beyond.

The legacy he left will live on because he realised that “better than money and fame, teaching martial arts to (his) children; giving them (his) time and confidence, is the best inheritance,” (Ahmadi, 1997).

Comments