Charles Mungoshi’s genius manifests

Stanely Mushava

Stanely Mushava

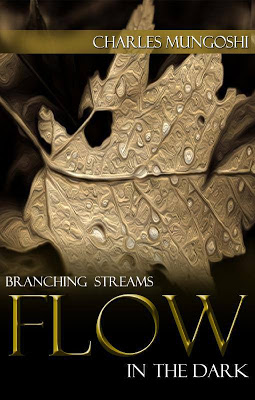

Book: Branching Streams Flow in the Dark

Author: Charles Mungoshi

Publisher: Mungoshi Press (2013)

A range of genius runs the tapestry of Charles Mungoshi’s latest novel Branching Streams Flow in the Dark.

The novel has occasioned a flare of rave endorsements from such notables as Lizzy Attree, Oliver Mtukudzi and Memory Chirere.

With the book having occupied Mungoshi for over 20 years, as his wife Jessesi said, it is fair to assume that a greater part of that time went to premeditating the title. The project comes across as a refreshing current at a time when Zimbabwean literature has ceded its traditional eminence and lapsed into a hinterland of obscurity.

More than that, it is a stream of consciousness, in the tradition of James Joyce, on an issue that has been seldom captured from the lenses of established writers; the plight of HIV and Aids patients in the face of stigmatisation and rejection.

Arguably the prime exponent of Zimbabwean literature, with a varied inventory of awards and international acclaim, Mungoshi brings his lyrical mastery to bear on the matter, with unsettling attention to detail, balanced with tender empathy.

To his credit, Mungoshi’s versatility does not wear across language, genre or thematic angle.

His dynamic facility in language, adapting it to capture the human condition in its alternate moods, is poignantly visible in this latest offering as in earlier works which elevated him to the presidium of local writing.

Keynote critics including Chinua Achebe in Morning Yet, On Creation have been riled by the failure of African literature to defrock it swaddling bands by progressing meaningfully beyond colonial hindsight.

Mungoshi can be spared this indictment. Although Mungoshi belongs to the infant dispensation of African literature which had running battles with the colonial establishment, he crosses the threshold with the same creative energy to provoke deliberation on emergent conditions.

Walking Still probes neo-colonialism beyond Independence while Inongova Njake Njake is a dysfunctional family portrait that bemoans the onslaught of modernity on family values.

Mungoshi is not new to the stream of consciousness medium as his other works, notably Kunyarara Hakusi Kutaura, confront readers with dissembling experiences of the heart, fresh from the source with nominal gatekeeping by the author.

The same medium has been exploited to widespread acclamation by his peer Chenjerai Hove in Bones, earning him several translations and the 1989 Noma Award.

It remains to be seen whether Mungoshi’s nascent title will excite as much attention, against the tide of lukewarm appreciation of literature currently assailing the local book sector.

Branching Streams flow in the Dark is only Mungoshi’s second novel, since his seminal 1975 masterpiece and international PEN award-winning Waiting for the Rain.

It may not share the complicated cross-currents of tradition and modernity that made Waiting for the Rain an inestimable nugget, but it remains remarkable in its articulation of a subject authors have generally shied away from.

“The issues pertaining to denial, stigmatisation and rejection are brought to the fore in the smooth flowing, dramatic and superlative language which can only come from the mind and hand of a seasoned writer in the calibre of Charles Mungoshi,” writes Dr Edward Chigaru in his preface remark.

The book revolves around the traumatic experience of the protagonist, Serina Maseko. She is diagnosed with HIV along with her baby who dies in infancy. Her husband deserts her to the scorn of those around her, including her mother.

The novel is cast in the form of a long letter, written by Serina to her former schoolmate Fungisai Bare in a desperate attempt to lift the weight of anguish off her heart. The passion exuded by the narrative knocks the reader raw and thrusts them into the place of the sufferer.

Mungoshi walks readers through the agony of alienation faced by people living with the disease, while silently indicting society for discriminating people living with the virus.

“I find it rather unfair to use this image, but I can’t keep thinking that if you ever wanted to know how a leper or an outcast feels like you should have seen me at that time when everybody including little children knew that Serina’s husband left her because she got Aids and she also infected her child with it and now the baby is going to die of it and the other baby may follow this one into the grave too,” unwinds the anguished Serina.

In her grope for an anchor, Serena turns to memories of youth, tries to recondition the past, as it were, but the world seems to be giving way under her.

Optimism sets in with her encounter with Saidi, who unravels lost connections, reunites her with her parents and husband, ultimately helping her recover herself.

Branching Streams Flow in the Dark, Mungoshi is an unsettling account of the challenges faced by families in the early years of HIV and Aids when being diagnosed with the disease equated to a death sentence.

Disenfranchisement of women, stereotyping and stigma against those associated with the pandemic leap out of the pages to awaken a society seared in conscience while suspense, intrigue and a musical flair enhance the aesthetic value of the novel.

The imperative of the moment is to bring Branching Streams flow in the Dark to the widest audience possible. A lax reading culture currently stands to impede the potential of local titles, however versatile, they may be.

Zimbabwe Book Publishers Association chairman Blazio Tafireyi remarked to Jessesi and I on the sidelines of the Book Fair last week: “Mungoshi is our own Chinua Achebe. When Achebe passed on he was a billionaire from the proceeds of his books. Why must Charles not enjoy the same financial success in his lifetime?”

Mungoshi was recently awarded the ZIBF @ 30 Certificate of Excellence, which was received on his behalf by Jessesi and Charles Jnr as he is still yet to recover fully from a coma he suffered in April 2010.

Comments