Addressing Africa’s reading culture

David Mungoshi Shelling the Nuts

In this instalment, I begin to talk about what happened at the African Union Pan-African Writers Conference held in Ghana as of 7-9 March 2018.

Africa’s depressed reading culture was among the major concerns of the conference.

Delegates agreed that Africa must rise and soar to heights where her languages can reign supreme. References to aviation are therefore deliberate.

Air travel has a classificatory effect.

It sets you apart from the millions of people who can only squint up at the sky to get a passing glance at an aeroplane passing by.

When you travel by air, you become distinctly different from the many bamboozled people who see a plane and wonder what it might be like on board.

Musaemura Zimunya, Zimbabwe’s most anthologised poet, has a poem about an old man watching a cloud-seeding plane in the sky.

The old man shakes his head and cannot understand such temerity as that shown by white men who go into the sky and puff smoke into the face of God.

When nationalist movements in Zimbabwe first began to talk about war against the colonists, it was not unusual to hear unconvinced peasants ask how people proposed to fight the white man who could go up into the sky where he was closer to God and therefore safe. Liberation must have seemed like the pipe dream of idle minds.

Anyone who has had the experience of herding cattle out in the country will know the huge bird that is known as the secretary bird.

When it takes off, it does so in the fashion of the aeroplane, running for some time and gathering speed as it flaps its wide wings. When the moment is right, it takes off into the sky and is off and away to heaven knows where in the distance.

When a secretary bird lands, what you see is a spectacle that seems to say whatever man makes the prototype is in nature.

Take the dragon fly for instance. There is no doubt that whoever invented the helicopter must have spent years watching dragon flies: their small wings and funny shape as well as their ability to stand still and hover in mid-air without ever falling.

The shiri yakanaka nursery rhyme is evidence of just how fascinated and even envious humans are with regard to the birds of the air.

We dream of flying one day, perhaps never like a bird, but at least in a vehicle that is much like the birds we see flying around practically every day almost everywhere. I too, like most other boys, always hoped that I would fly one day.

My first flight was from Harare to Bulawayo and back again. I was part of a team from the Curriculum Development Unit (CDU) on a mission to schools in Bulawayo.

I sat next to a man who had seen it all in so far as air travel was concerned.

He’d flown around the region and to and fro Europe zillions of times and was, therefore, an old horse in this kind of thing.

As the delicate Viscount hit stretches of turbulence, our ride became bumpy and I found myself sweating profusely.

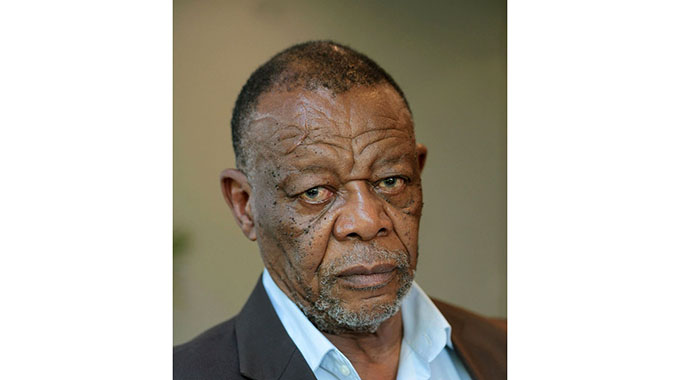

Wally Mongane Serote

Fear gripped my pounding heart in a vice-like grip and would not let go.

The man looked amused. Nevertheless, he whispered to me that there probably was a water body beneath us and that it would all be alright in the end.

The reeling in my head, the ominous growls in my stomach and the height of the plane above sea level made my debut flight one full of fright.

My heart was in shreds and I was paralysed by a deep fear of the unknown. These two things conspired to make the flight a nightmare. I could not understand how a whole house on wheels could rise and stay afloat in the air for hours on end.

This defied everything I knew about the force of gravity and made me feel that I was tempting fate sitting on air high up. Although I knew that a human being could never be a bird, the prospect of flying was as attractive as it was fearful.

The pilot said, as other pilots would do on many subsequent occasions, we had begun our descent and would be landing in about half an hour.

The pounding in my ears was at crescendo level and I felt like my chest was going to burst open. How was he going to land the plane I wondered?

I closed my ears as the wheels touched the ground, hoping against hope and praying fervently that we had a safe landing.

At that point in time, I would have been grateful to anyone who could have knocked me out and saved me the anxiety of the landing. That I had somehow made it to Bulawayo by air without mishap was a marvel to me.

Thereafter, my pleasure rose as my fear of flying receded.

In some respects, technology has begun to make airports not so pleasant. You are thoroughly screened and your baggage is scrutinised thoroughly.

These experiences can take some of the joy out of flying. What with the body-checks and other intrusive practices. Checking in can be quite disconcerting. What with the incessant stops and questions that make you wonder if you have suddenly become a wanted person.

That the diligence shown by security personnel at most airports is necessary cannot be denied.

This is necessitated by the actions of people with criminal minds. These malevolent people give travellers a bad name. I could not help feeling affronted as I made my way through immigration on my way in and out of Ghana through Accra’s Kotoka Airport recently.

Each time I was stopped, a young lady with plastic gloves on her hands said something about narcotics.

I wondered what it was that made them think I could be carrying drugs on me. That aside, my most recent trip was quite pleasant in some ways.

The African Union recently called and sponsored a Pan-African Writers Conference to chart the way forward with regard to matters of concern to the continent’s book chain.

Former Ministers of Education and Culture were there as were the veritable array of professors who gave the occasion an air of erudition.

Thinking about how the inimitable Dambudzo Marechera might have reacted to such an overt display of political correctness, I could not help the chuckles.

At this conference, when diplomats and bureaucrats addressed the gathering after an invariably lengthy outline of their exploits, they tended to leave the writer for the periphery of their speeches.

As a writer, I did not feel particularly elevated or appreciated.

Marechera would most certainly not have tolerated such a thing. There would have been hell to pay and one or more persons would have been at the receiving end of his lashing tongue.

What made things worse was the manner in which French-speaking delegates would always appear to speak forever.

They always seemed to have quite a lot to say and did so in the most roundabout manner.

Circumlocution was an obvious forte of theirs. They excelled in it without effort. When I quietly remarked on this, a colleague from an English-speaking part of Africa said French had in the past been the language of refinement and diplomacy and that its speakers appeared to savour the grand stage where they could be at their flamboyant best.

At the conference, I met a representative of “The Thabo Mbeki Foundation”; the organisation that had underwritten the conference: He is a man whose name I had always held in reverence, a pioneer of modern South African protest poetry. Wally Mongane Serote!

Our first conversation together was quite hilarious because I seemed to have been in a time warp. I said to him, “Wally, I have always imagined you as a young angry man from Soweto.

“I was always reading your poems and could see you and others authoring the Soweto uprising.”

Serote laughed without ire and said he had indeed been young, angry and active in 1976.

He said if Steve Biko was alive today, he would be in his late sixties and close to 70.

Adama Samasekou, a former Minister of Education in Mali, spoke about the need to allow greater autonomy for African languages in former French colonies.

Later, when I asked him in private if France would allow such innovations, he said he didn’t think so.

Professor Senkoro, a Tanzanian academic, currently at the University of Namibia, was all for Kiswahili being adopted as one of Africa’s lingua francas.

On the last day of conference, Hilda Twongyeirwe, the executive director of the Uganda Women Writers Association, received a standing ovation during Uganda’s jubilee celebrations.

She was honoured for her work in uplifting the lives of Ugandan women through the pursuit of writing.

Zimbabwe could take a leaf from this. Elsewhere in Africa, writers qualify for diplomatic passports.

David Mungoshi is a writer and editor.

Comments