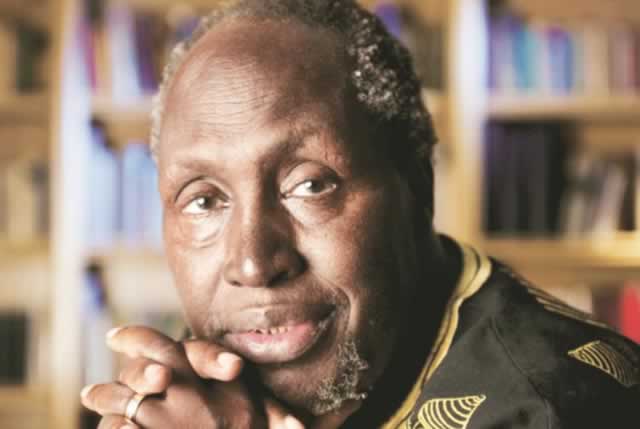

A portrait of the dissident as a young man

Stanely Mushava Literature Today

Ngugi’s attachment with the freedom fighters runs deeper than platitudes: It is a question of blood ties. Earlier in his childhood memoir, “Dreams in a Time of War”, his brother Good Wallace has escaped to join Mau Mau, narrowly escaping “a hail of police bullets”.

Book: In the House of the

Interpreter

Author: Ngugi wa Thiong’o

Publisher: Pantheon Books (2012)

ISBN: 978-0-307-90770-7

Ngugi wa Thiong’o has emptied his drawers for a collage of his teenage portraits, tagging along the cultural and political landscapes of mid-century Kenya.

“In the House of the Interpreter”, the second instalment of his memoirs, presents the formative phase of the author’s “intellectual and spiritual strivings”.

A thread of meticulous records lockstitched by a seasoned hand, the book is a coming-of-age narrative as much as it is an account of colonial Kenya.

The “house of the interpreter,” is not another site of linguistic controversy, as may be anticipated in light of Ngugi’s famous language debate. It is Alliance, an African high school run by Franciscan devotee Carey Francis, incepted as a joint venture of Protestant missions.

The title comes from a passage of a theological import cited by Francis from John Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress”. In the passage Christian, the Zion-bound protagonist of Bunyan’s classic is taken into a parlour full of dust during a visit to the Interpreter’s house.

A cloud of dust almost chokes the onlookers while the house is being swept, only to settle when a woman sprinkles water on the floor. “Then said Christian: What means this? The Interpreter answered: This parlour is the heart of a man that was never sanctified by the sweet grace of the gospel,” Ngugi recounts.

“The dust is his original sin and inward corruptions that have defiled the man. He that began to sweep at first is the Law; but she that brought water and did sprinkle it is the gospel,” Ngugi divides the scriptures.

For his admistrative purposes, Francis likens Alliance to the Interpreter’s house where the “dust brought in from outside could be swept away by the law of good behavior and watered by the gospel of Christian service”.

A liberal deployment of Christian images runs the tapestry of the book, though nothing is to be appropriated at face value. Irony is in the detail, coming from a writer who has publicly repudiated and trained a series of polemics on Christianity.

The interpreter at Alliance is the cultural gatekeeper of the colony who explains the world to the native. His brand of Christianity is customised to pander to the colonialist outlook.

All the same, Ngugi the cultural nationalist and Afrocentric iconoclast, now given to denouncing just about everything he deems foreign, ushers the reader back to the most unlikely of beginnings.

It is hard to tell how many of the early attributes have survived, though Ngugi’s ardent devotion to theatre and the budding sense of identity recounted in the memoir have since sprung full flower.

Ngugi revisits a hitherto unknown episode of life: his one-to-one ministrations as a Jesus-is-my-personal-saviour evangelist and Christian apologist after being convicted by a Billy Graham playback during a crusade.

He maintains the holy office at least to the threshold of Makerere University, traversing neighbouring communities in search of new converts.

Although he has since renounced the faith, announcing elsewhere that he is rather at home with the pantheon of indigenous deities, a part of those formative strivings is still superimposed on his work.

Ngugi has acknowledged the influence of the Bible on his work, albeit in a fractured format, as a literary styleguide rather than a spiritual authority.

Again, as with most intellectual notables, there is that inadvertent allusiveness to traditionally Christian values without acknowledging their cradle.

In the memoir, though, we encounter Ngugi fired up for the scriptures both for their literary value and for their spiritual power, although his inability to answer sceptics seems to set the stage for his later scepticism.

Away from this crisis, Ngugi also struggles to process the ambiguity of the black identity in a colonial setting. His European orientation at Alliance High School is at odds with his growing political consciousness, the latter being reinforced by concrete cases such as the displacement of his people from their homes to concentration camps as a settler stratagem for isolating Mau Mau.

The conflict is captured in his appraisal of Booker T. Washington’s autobiography. Whereas Ngugi identifies with the former slave’s thirst for education, and his values of hard work and self-reliance, he is uneasy with Washington’s complacence to the imperative of social equality. For young Ngugi, “self-reliance and self-effacement were contradictory ideals”.

Ngugi’s attachment with the freedom fighters runs deeper than platitudes: It is a question of blood ties. Earlier in his childhood memoir, “Dreams in a Time of War”, his brother Good Wallace has escaped to join Mau Mau, narrowly escaping “a hail of police bullets”.

His family has been stalked by anti-Mau Mau inquistors. Ngugi himself is required to get “a Bill of political health” before securing a safe sojourn at Alliance. The Bill consists of certification by his home authorities’ certification that he is not signed up to the guerrilla unit’s oath of allegiance.

Although he is determined to stake a claim in the black meritocracy of colonial Kenya, successive jolts of history keep Ngugi’s sensibility at odds with the settler dispensation. “How could a whole village, its people, history, everything, vanish, just like that?” he queries when he finds, on his first vacation, his village forcibly uprooted by the settler administration.

Ngugi anticipates an encounter with the brutality of the system from which Alliance offers a temporary sanctuary. Upon enrolment, he feels as if he has “narrowly eluded pursuing bloodhounds in what had seemed a never-ending nightmare”.

Three years before his admission, the colonial government has declared a state of emergency, creating conditions of perpetual insecurity for young Ngugi who suffers “constant fear of falling victim to the gun-toting British forces that were everywhere, hunting down anticolonial Mau Mau guerrillas, real or imagined”.

“Now I was inside a sanctuary, but the hounds remained outside the gates, crouching, panting, waiting, biding their time,” Ngugi recounts. When the hounds finally pound towards the end of the memoir, the colonial dragnet hauls Ngugi into detention where the innocent mingle with hardened criminals.

After an omnibus of nightmares and an atrocious odour in an overcrowded cell, Ngugi records an argument on courage from an elderly prisoner: “There is no courage in snatching people’s wallets, be they European, Asian, or African,” he says. “Courage is in those young men and women who took to the mountains to face an enemy armed ten times more than they, not for their individual gains, but because they were responding to the cries of a community.”

Ngugi recounts the demobilising impact of the execution of Mau Mau kingpin Dedan Kimathi, around which time his brother, Good Wallace, is taken prisoner. The demobilisation of Mau Mau concurs with the emergence with an elite crop of Kenyan nationalists. He recalls Tom Mboya’s famous “Scram from Africa” speech: “From scramble to scram: the speech made the 28-year-old Tom Mboya a household name in Africa,” he says.

There is not much in the early segments of the memoir to suggest the development of the great writer Ngugi would later become. In the early chapters, he erroneously believes that one requires a licence to become an author.

His literary strivings begin in earnest at the head of the last third of the memoir. By then, he has devoured a stack of classics including Alan Paton, Emily Bronte and Leo Tolstoy. Scarcely into “Childhood” “Youth” and “Boyhood”, Tolstoy’s memoirs bound into one volume, Ngugi recounts the coursing in of an urgent desire: “I wanted to write about my childhood. Before, such feelings had been vague and fleeting, not calling for immediate action. This new desire was insistent,” he re- calls.

This leads to the writing of Ngugi’s first short story, “My Childhood”, published under a misleading title, “I Try Witchcraft”, in the school magazine. To his dismay, the editors make free with the script, throwing in insertions which violate his creative spirit.

The climax of Ngugi’s spiritual strivings is his conversion of a sceptic after a long dry evangelical spell, immediately followed by his triumph in a court case where he answers trumped-up charges of violently resisting arrest.

We leave a mild, young Ngugi packing for Makerere.

Comments