Zimbabwe: The rise of spectator democracy

become.

In the aftermath of the war, the Creel Commission successfully used the acquired propaganda tactics to launch an attack on unionism in the United States, whipping up a hysterical Red Scare, and successfully destroying workers’ unions and eliminating such dangerous problems as freedom of the Press and freedom of political thought.

The propaganda model was superbly supported by the media and business establishments, as well as by the intellectual community, especially the intellectuals of the John Dewey era — themselves overly proud of being the “more intelligent members of the community,” as Noam Chomsky would put it.

In quite an impressive and indisputably successful way, this group was able to drive a reluctant population into a massive war by simply terrifying them to the point of eliciting jingoist fanaticism.

All it needed was a good deal of fabrication of atrocities attributed to the other side, like making up stories of Belgian babies with torn off limbs, and all sorts of awful things recorded against the Huns that one can easily read in history books today.

The Americans borrowed much of the fabrications from the British propaganda ministry, whose declared objective was “to direct the thought of most of the world.” US intellectuals were roped in, them in turn passing on the concocted propaganda for facts, successfully converting a passive country to unprecedented war-time hysteria.

It was like the 9/11 effect on the US population in 2001.

This experience shows that state propaganda can have a huge effect on democracy, especially when it bars deviation and when supported by the educated classes. Hitler himself believed so much in this political doctrine, and the doctrine keeps Western democracies ticking to this day, just like it is used by totalitarian regimes.

Liberal democratic theorists like Walter Lippmann got involved so much in the propaganda commissions of the time and immediately recognised how much could be achieved through them. The prominent journalist ended up arguing that “revolution in the art of democracy” could be positively used to “manufacture consent,” essentially to make the public agree with what they do not want.

Not only did Lippmann think that using propaganda techniques to manufacture public consent was a brilliant idea, he also believed it was an absolutely necessary phenomenon, as the idea is treated today by modern democracies. His reasoning was impressively frank. He argued, “the common interests elude public opinion entirely,” and that such interests can only be understood and managed by a “specialised class” of “responsible men,” who are privileged to be the only ones intelligent enough to figure out life’s complex realities.

This theory that asserts that only a small elite can understand common interests has become part of Zimbabwe’s political culture and one has to look at how the so-called Global Political Agreement came to be regarded as part of Zimbabwean democracy to see this, just like at the ongoing encyclopaedic confusion called constitution making, as carried out by a few thoroughly misguided intellectuals in the name of “what the people said,” or worse still, “what the people need.”

For the GPA, Zimbabweans had to endure nine months of keeping track with terribly frustrating political negotiations carried out by six people, namely three lawyers, a diplomat, an accountant, and a female political activist. To these six had been bestowed the power of reason that is often deemed to “elude the general public,” in the words John Dewey. So the six would repeatedly retreat to hotels and conference rooms in South Africa to shape for Zimbabwe the common interests that are too complex for the unthinking public.

They were entrusted to package their political aspirations as the common interests of Zimbabweans in general; creating in the process a long list of largely duplicating government ministries designed more to accommodate political aspirants than to serve the needs of the country. In the GPA negotiations there was perfect logic in ensuring that politicians that had been humiliated by the electorate in the 2008 election were elevated into national leadership, like Arthur

Mutambara, Welshman Ncube and Priscilla Misihairabwi-Mushonga — all losers in the March 2008 parliamentary election, but logically reinstated to national political leadership by the complex reasoning of the educated among our people — a reasoning so complex that it eludes the stupid masses.

Now we have COPAC doing the intellectual rounds of confusion with the draft constitution, repeatedly retreating to expensive hotels to “deliberate on the draft,” and promising to come up with a “properly compiled draft constitution,” for Zimbabwe.

The intellectual and political protagonists in COPAC are essentially stuck over disagreements that have next to nothing to do with the common interests of the people of Zimbabwe. Among hundreds of clauses and sections in dispute are issues like accommodation of gay rights, federalisation of Zimbabwe, dual citizenship, lower and upper limit to the age of presidential candidates, role of the military in politics, and so on and so forth.

Gay rights are being debated as a sponsored issue mainly being pushed by the Western-sponsored civic society.

Federalisation, or “devolution of power,” as it is being proposed, is an initiative of political aspirants that view their own ethnicity as a threat to their prospects of ascending to national prominence, or conversely they view other ethnicities as unfairly advantaged by numerical values in the game of national politics.

The issue of an upper age limit to the presidency is a proxy effort at expressing frustration by the opponents and rivals of President Robert Mugabe — an effort more to do with dealing with the incumbency of one hard to push politician and far less to do with age itself being a demerit in governance issues.

Debate over the security sector’s role in politics is the MDC-T’s way of countering the otherwise meritorious accusations of treachery and puppetry coming in the direction of Morgan Tsvangirai from the military leadership, and essentially from everywhere else.

Only the constitution can make radical generals respect the rule of Western puppets, and of course in the name of democracy; so goes the reasoning.

The view that what all of us care about can only be explained and articulated well by a few elites is typically a Leninist one — that concept of vanguard revolutionary intellectuals taking power on the ride of popular revolutions, using people power as a force to gain power, and then skilfully driving the stupid masses toward a future they are too dumb and incompetent to comprehend.

In the first five years of the MDC, Morgan Tsvangirai believed he could whip up public emotion to the level of carrying out a mass revolution through which he would rise to state power — power he would then use to push back the masses to a future defined by Western capital and foreign policy, even dreaming for a while that the stupid masses “mushrooming on farms,” and “destroying productive agriculture,” would be “evicted from the farms” they had occupied at the expense of colonial white commercial farmers.

Of course Tsvangirai met a state power that was too strong for his plans and history has a telling record of how the planned mass protests flopped, with the last one in March 2007 leaving Tsvangirai displaying only bruises of failure to the entire world.

The common ideological assumptions between liberal democrats and Marxism-Leninism are quite similar, just like the ideological assumptions of liberal democracies and dictatorships are essentially the same. That is why it is easy for liberal democrats to instantly switch to dictatorship, and also for dictators to instantly convert to liberal democracy.

All that needs to be done is to assess where power lies and say if power is in a popular revolution, let that revolution put us into state power; or maybe we can rely on the power of business and corporations to get the same power; or who cares if that power will come from the military, for as long as it takes us to state power.

In the end we will just have to drive the stupid masses toward a world they are too dumb to understand themselves, a world of complex matters like thinking on behalf of the unthinking lot ignorantly walking the streets of the country!

If the power is in Western funding, let us use that power to gain state power; if the power is in civic organisations, in war veterans, or in the youth, let us just use that power; but purely on the same assumptions and objectives of accessing state power, never ever to share it with the unthinking masses but to let it benefit us politicians and the power centres that thrust us into political office.

After all, the masses are like three-year-olds — you cannot reasonably entrust them with complex matters of life.

As Lippmann aptly argues, there are two classes of citizens in a democracy, the specialised class that always talks about what to do about and on behalf of those all others, and of course the class of “those all others,” — the bewildered herd whose function in a democracy is to be “spectators” in the complex action of the thinking elites, when they are not enjoying those moments they are allowed to lend their weight to one or the other member of the specialised class through programmed elections.

Precisely that is why incumbent politicians believe by merely looking at their action plans and adding to them their personal political aspirations they by definition become not only indispensable but also unreplaceable. Morgan Tsvangirai has become to his brand of the MDC what President Robert Mugabe has become to his Zanu-PF — hard to replace politicians in whose absence an election has become so hard to envisage.

This is what happens in any spectator democracy out there, like US citizens were made to choose only between the hated war-mongering George W. Bush and the unassuming John Kerry in 2004, pretty much the same way most of the bi-partisan Western democracies present their candidates to the electorate, more for ratification and far less for choice.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death.

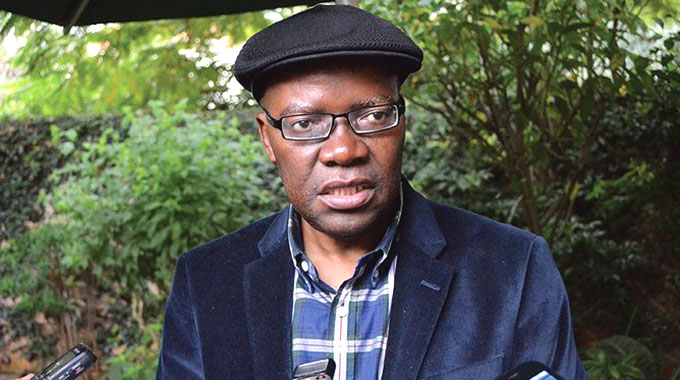

Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in Sydney, Australia.

Comments