William Punch: My accursed heritage

Nathaniel Manheru THE OTHER SIDE

I AM reading an autobiography of Francis Robert Thompson, better known in our history as “Matebili” Thompson. You notice I avoided “by”. It is an autobiography in the loose sense of the word, for the book was put together posthumously by Thompson’s daughter, Nancy Rouillard. Her father died in May 1927.

But the bulk of the material for the book directly came from the hand of the late departed, who was already working on his own story when death met and overtook him.

So much to do, so little time to do it, said one Rhodes.

For those with a weak sense of history, “Matebili” Thompson was, alongside Charles Dunell Rudd and Rochfort Maguire, responsible for the fateful Rudd Concession of 1888, a concession which paved the way for the Royal Charter a year later, and for the eventual occupation of our country by the British, through Cecil John Rhodes.

By the time Matebili Thompson finally accepts the pleas to write on himself and, through that exercise, on the “exact” circumstances of the Rudd Concession, Thompson is the only survivor from the concession trio. His narrative efforts are thus rated key to Rhodesian historiography.

Writing their own history

Typical of that historiography, the book has several key illustrations of historical value, to be exact, 17 all told. I always find these illustrations much more fascinating than the narratives which imprison them, narratives which are racially skewed and coloured as a matter of collective white habit.

I have never begrudged Rhodesians for that slant, irritating though it might be. It is their rendition of history; it is their history and thus part of a body of narratives purposefully linked to the construction and reconstruction of their collective personality, both as lived and as wished. Rhodesians do not have to be fair to anyone else, least of all to the blacks they so reviled for all times as mere minors in, and objects of, history.

When we decide one day to reclaim or reconstruct our own grandeur, I am sure we will have the sense to pick up our own excavators, shovel and pens, to give the world our own story, and one purposefully linked to our existential needs and imagined collective personality, both as lived and as wished. For such is the role of history.

When history is not the past

I am taking it for granted, dear reader, that you are familiar with Jenkins’ key distinction between the past and history, between facts of history and narratives. To restate Jenkins, history is not the past; it is about the past: a mere version, narrative or reconstruction of a complex past. It is a discourse, a rendition of some aspects drawn from the past, shaped by pressing values and needs of the present.

Strictly, while we have the past, in actual fact we have histories. Never a history. For there will be as many narratives on, and about, the past, as they are narrators keen to focus on a given past, indeed as many histories as they are interests to be embedded, advanced on defended through those narratives.

Jenkins makes the point even more vivid. When you go to college to read history, you do not board a shuttle bus on a journey to some country, some place, some occurrence or some age called the past. You do not travel to Munhumutapa to meet its empire and emperors as they lived in that past. Rather, you go to the library to comb through shelves of books. We read narratives of the past; we never meet or read the past itself. Keep that in mind, dear reader, so you free yourself from the aura and claims of given histories, of given historians.

An illustration of white history

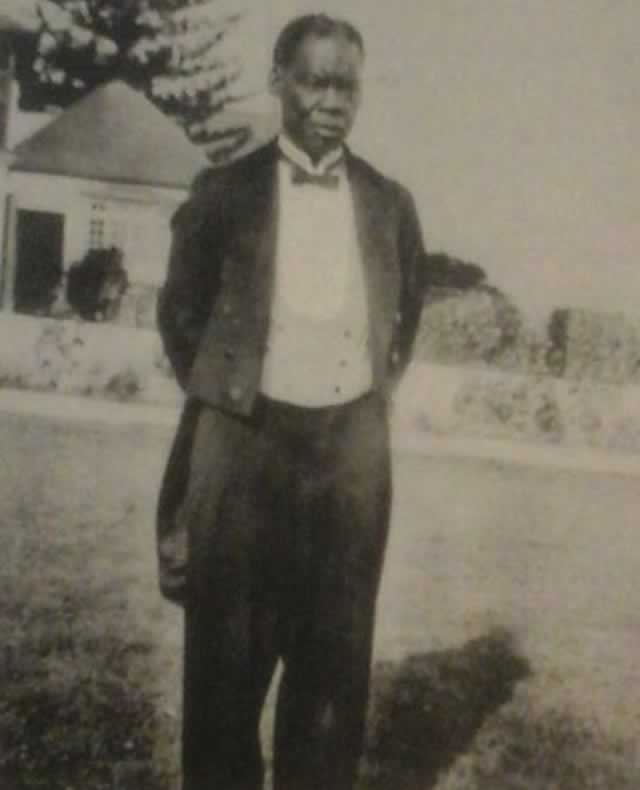

Among the 17 illustrations in Thompson’s book is a picture of a native in a waiter’s apparel. Splitting his expansive head – from forehead to just before the head’s declension – is a “dharakishoni”, a fashion statement by way of a line to the scalpel, contrived through splitting hairs on either side of his big African head.

At the time of being photographed, he would have been in his early sixties: a serious character carrying a face of fierce loyalty, a face decidedly fearful of authority. Given the times, there is no prize for guessing what or who that authority was. There is an elaborate caption at the foot of the picture, starting of course with his name: William Punch.

After the name comes the following words which I reproduce faithfully: “As a child Punch, a Mashona, was bought by F.R. Thompson as a slave. He was a victim of one of Lobengula’s raids, his parents being killed in the usual massacre accompanying such expeditions. He was brought up by Thompson as a house servant, remaining with the family all his life, and on occasion travelling with them in Europe. He became warmly attached to his master and survived him only a few years. His last request, which was granted, was that he should be buried at his master’s feet.”

Know thy native

Right on the second page of his first chapter, Thompson explains why Rhodes picked on him for the Rudd Concession assignment. He says, “I think Rhodes sought me out because of my knowledge of the natives, and of things South African generally”. Gentle reader, keep in mind that far back then, South Africa meant the whole of Southern Africa, excluding of course territory controlled by the Portuguese, the Boers and the Germans. Such that when Thompson talks about “my knowledge of the natives”, he encompasses our forebears too, those natives living up north, beyond the Limpopo and beyond the Zambezi.

He spoke many native languages, knew the ways of native minds, both experientially and through contact with missionaries and hunters and traders, which he himself was. The task of extorting a country, while projecting a sense of native complicity in that theft, needed a deep grasp of the native mind.

As I write this piece the Obama precedent seems to have finally caught up with the rest of the world. Next to us, only down South, we hear of one Mmusi Maimane, a black South African who is said to have taken over the leadership of the Democratic Alliance, taken it over from Hellen Zille.

Black South Africa is agog, wrapt by this “extraordinary” development involving one from their vast number: that of scaling up to lead a party of white politics and white interests as reconfigured for a post-apartheid milieu. Appropriately, Maimane is married to a missus, a white lady, an occurrence which appears most unfortunate in a country with a politician in the mould of one Julius Malema!

I see devastating taunts as sure to follow should Maimane make the fatal mistake of crossing the hallowed path of EFF, Malema’s party. Interestingly, the coverage around this chosen one has not focused on how he is likely to transform the DA into a party of the black majority. The focus has been on his competence to represent white interests under a black government. The cynical ones have gone as far as stating that such an assignment cannot be a tall order. He is already fulfilling it anyway within his rainbow household!

When two sevens clash

The less cynical ones have seen this as proof that the black man in South Africa is on the rise, virtually now eligible and trustworthy to interpret and run the white establishment. Not once have I got a sense of a takeover. No. It appears no one in South Africa expects or demands it. It has been all about receiving small, tender mercies from a compassionate establishment which is white. And the assignment is clear: to win the demographic factor in politics so continued white dominance has a popular black base.

Maimane, some commentators insist, is about what a black man can do to save white vote. Now we seem to know where Zille’s stomping was taking South Africa to. Or her attempt to engraft Mamphela Ramphele onto the DA, an attempt which fell flat so spectacularly. But not before it had made the idea of a black leadership of the white Democratic Alliance thinkable.

An “Obama of South Africa”, Maimane is now called, without much clarity on whether or not this is meant to foredoom the ANC. Key to the whole leadership colour transformation is to remember this is happening at a time when white South Africa and black South Africa appear headed for a defining clash. What has colour to do with it, one might wonder. So much about our neighbour.

Black in Labour

Further afield, you have Chuka Umunna, a product of a Nigerian immigrant. A lawyer by profession, by politics a shadow business secretary from Labour Party, Chuka is a Briton who until a day or so aspired to take over the leadership of the British Labour Party, a party well at the nadir of its fortunes. Having proclaimed his wish to run for leadership, it would appear our Chuka’s feet have gone cold, all in the name of friends and family who might not suffer the scrutiny and spotlight accompanying a leadership contest.

The wish to lead Labour has become nightmarish, a real case of black man’s labour! Could this suggest skeletons in the cupboard? Or could this be his own admission that race remains at the heart of British politics? No, says Chuka, in clear Caucasian tones that seem calculated to renounce his African heritage, to blot out any traces of Africanness or Africa, the continent of his forbears.

And that tone rests the speculation on what he was likely to give Labour in leadership. Certainly not leadership with an African, immigrant touch, but a Briton with an incidental African parentage. Peter Mandelson gave him a very good chance, if not for now, certainly for in the future. He is only 37. And Mandelson knows Chuka well, Chuka the native. I hear Britain’s demography is fast changing in favour of immigrants, most of them black. The ethnic will soon matter. Very interesting times indeed! By the way, is Tendai Biti still around? Or has he gone back to America?

In-law, in power

Today the world proclaims itself as post- many things: post-structural, post-communist, post-liberal, post-modernist, etc, etc. Another post- is what one might term post-colour, post-complexion. The world of colour bar is now dead, we are told everyday, never mind that our television screens – themselves screen-savers of our coloured age – will give us one or two black newscasters, all to pre-empt charges of racism.

Never mind that the white officer’s gun is always trained on the African-African American, and all this under Obama’s rule. It is a post-colour world, but one exhibiting a peculiar colour hyper-consciousness. The needs of colour of our age are met, it seems, by tokenism. Or dodged through the same.

After Obama, American power politics can no longer plausibly be charged as racialised. A black man has been to White House. And has messed up. You can’t blame the white world. Similarly, after Maimane, no one can charge South African whites with crimes of apartheid or racism. Behold the colour at the helm, I hear them screaming. The British establishment has been naturalising colour, so leech-like, it fastens on the margins of real power, what with the likes of Baronness Amos and many some such.

Today it says black can even aspire to lead. And freely withdraw that aspiration. To guarantee millennia of enjoying racialised white power without charges of illegitimacy, a two-term inconvenience under a black Obama is a small price to pay. The key thing is to find the “correct” black, which is why all resources must be deployed to that end, including sacrificing a few white daughters, all to know the good native. Marriage safely puts white power in the hands of trusted in-laws. And marriage is anything that socialises the black man well so he is a obedient minder.

Deeper, more hurtful than scar

Matebili Thompson knew the native by grasping their language. By playing with him in the playground of childhood. By being served by him as a kaffir in his father’s household. By being his ox driver and guide in his hunting journeys “up North”. By being his opponent in frontier wars. By alienating his land. By being a trader who dealt with natives to procure ivory, ostrich feathers, cattle, grain, etc, etc.

Above all, by “buying” him from tribal slavery into colonial slavery. And by taming him through chores of a “house servant”. All these are physical processes, and depending on how they are handled, they are bound to trigger resistance and eventual opposition. These extrinsic interventions towards “knowing” the native, don’t bother me much.

What does is the insidious mores of servility and service to the white man and his establishment which comes with such conquest. What bothers me is “marriage” that makes one a dutiful in-law to white interests. That most kindly, most delectable assault which made Matebili Thompson appear in the eyes of William Punch as infinitely kinder, better, infinitely more humane, than the conquering and enslaving Lobengula. That most kindly assault which creates in the mind of William Punch his last request “that he should be buried at his master’s feet”, thereby reproducing even in the quiet cemetery the Rhodesia’s racial hierarchy.

Comic relief in white cast

The caption beneath the picture figure of William Punch is a pregnant one. First, he is William Punch, a name fundamentally at odds with his resume as a Mashona conquered by a Ndebele monarch. The new name kills his double African identity, never mind the grief which that double African identity carries. It does worse: it turns a serious, full-blooded African into a comic character through a new appellation.

He is renamed by the white man, has his original Shona name overwritten by white whim. He embraces the new name, the new person he becomes through death to the old one. The “punch” of his name did not refer to what a clenched fist does to the wrong-doer. It drew from the paraphernalia of the kitchen, most likely by way of the name of a drink which the master favoured.

And in memory, that love was pasted on the servant for all times. And for routine humour, that name was pasted for all to call, for me to embrace as my heritage. A people meant as comic relief in a white cast. And this fall from the sublime to the comic is so total that today, I can only recall, write and report on this Mashona double captive by only that name and no other.

Maybe he was a bvumavaranda, a museyamwa, a simboti, I don’t know. I will never know. To name is to own, and Matebili owned this Shona captive: physically and by way of an imparted identity.

Native dutifulness

But William Punch lived and died a fulfilled soul. He lived indebted to Thompson for “buying” him from and out of a cruel destiny in the hands of a bloody monarch. And being “bought” from the viewpoint of William Punch equated to being “liberated”.

And being turned into “a house servant” was not some form of indenturing, was not a continuation of slavery; it was the height of white favour. A favour taken higher by way of “on occasion travelling with [the master] in Europe”. Under the Ndebele Kingdom, you won your freedom in war, in future raids, never mind your origins.

Under Matebili Thompson, you remained a creature at the white man’s “feet” right to the cemetery! Yet fate under the white man seemed safer, better, kinder! And wearing a waiter’s garb amounted to a statement on civilisation which had arrived, a proximity to the master’s culture, itself the acme.

Such that when taken in sum, it is less about knowing the native, more about making him one through immersion into an ethos in which servility is liked and craved for. It is that immersion, that conviction that by subduing you, the white man has done you enormous good, that then creates a psychosis of tenacious loyalty and subordination to the white man. A loyalty that leads to self-abasement.

This could come in the form of marriage, of education, of politics, of a managerial position, etc, etc. It creates a mental outlook. Never of freedom, never of service to one’s kind. Quite the contrary, it creates a desire to persecute your own, so you ingratiate deeply with the white master, carry his cross, which is why a black man is the best insurance in defence of white interests at a time when the demos are likely to rise. To be a dutiful in-law.

“His last request, which was granted, was that he should be buried at his master’s feet”. Oh William Punch, my accursed heritage! But where is Tendai Biti?

Icho!

Comments