When race places a wedge in love’s eye

Elliot Ziwira @ The Book Store

Imagine a world without boundaries, where love knows neither race nor ethnicity, where everyone else is a friend regardless of age or level of presumed education. Just imagine, a world without hatred or violence, where soothing music brings us all to the dance floor; and we flawlessly skank all our worries to oblivion.

Just imagine!

There is so much suffering in the world, so much pain and hurt; but why? Everyone is ever busy scheming against everyone else; to what end? Now as we are all gouging out each other’s eyes, who will lead us out of this darkness of our creation?

Stranded on the dance floor, without music, as the wren, our lead vocalist has lost her melodious tune in the insidious smog of malnourished civilisation, we attempt to twerk out of our stupor, but it is hopeless. We look around and see hideous images of ourselves in the mirror and we go crazy.

In blind rage, we attack the mirror but the images multiply in the smithereens that scatter everywhere, as our ire is taken to every nook of the world in each of the scattered images; grave pure hate. But why?

Gentle reader, I have been reading; always reading to find the source of our hate; yours and mine, and I have discovered that the more I read, the closer I come to myself as the source of my pain and that of others. Have you been reading lately, gentle reader? Find something close to you and read, anything.

There is a book, a play to be precise, that I have read over and over again, in an attempt to have it speak to me from a different angle, and each time the characters change timelines, but remain the same in their quest to wrestle hope from the clutches of an albatross that crouches on the horizon of their aspirations.

Athol Fugard’s timeless play “Master Harold . . . and The Boys” (1982) pokes into the psychosis of racism with such force that all of us are exposed as deceitful, vain and hypocritical. It is not so much the colour of our skin that is at fault; be it white, black, yellow or otherwise, but our capacity to hurt or hate is simply immeasurable. But if we decide to be compassionate, without the prejudice of race, religion or ethnicity the world would be a better place for us as well as our progenies.

The setting is a tea shop in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, in 1950. All the events take place in a single afternoon as episodes in the past reel into the present through flashback. Central to the storyline are three characters – Hally (Master Harold), a 17-year-old white boy in Standard Nine, Sam and Willie — black servants to the Harolds in their mid-40s.

Sam and Hally are on first name terms because they are close, but Willie calls the white boy whose mother is their boss, Master Hally or Master Harold. As the play begins Sam and Willie, also close, are preparing for a dance tournament, and are joined by Hally after school. The boy tries to take to his books and let the two men concentrate on their session, because there is no work to do in the heavy rains, but he fails.

The playwright adeptly plays around the concepts of friendship, religion, familial love, bonding, intelligence and education through the thorny issue of race.

Through the use of imagery, symbols and metaphors drawn from both human and nature’s armories Fugard hilariously hoists the audience on an all familiar terrain of boundless love and friendship.

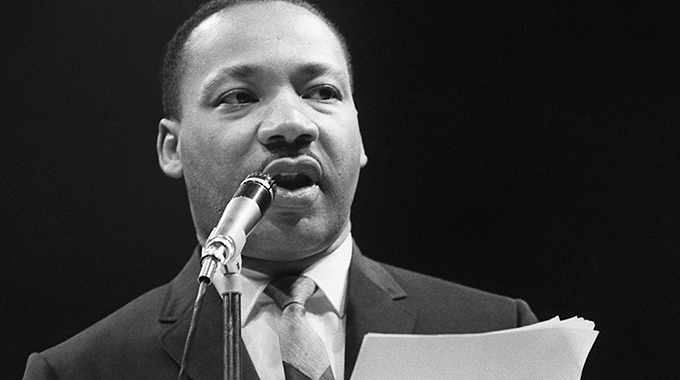

The trio shares their fears on the political logjam that scuppers progress and lay hopes on the transient nature of oppression and the rise of social reformers; as Hally tells Sam: “It’s a bloody awful world when you come to think of it. People can be really bastards. . . I oscillate between hope and despair for this world as well, Sam.

“But things will change, you wait and see. One day somebody is going to get up and give history a kick up the backside and get it going again.”

There is so much hope that apartheid and its attendant follies will be emasculated; so thick that one would cut it with a knife.

There is hope for humanity as Hally takes Sam through his books for him to be enlightened about the world of Western education, though he always tells him: “Failing a maths exam isn’t the end of the world, Sam. How many times have I told you that examination results don’t measure intelligence?”

He always reminds him of Winston Churchill and Leo Nikolaevich Tolstoy, who “did not distinguish (themselves) scholastically”, but were men of magnitude. Sam, who has gone up to Standard Four because of racial prejudice against people of colour, exudes intelligence, as he takes Hally on, on any topic with such alacrity that leaves the reader dumbfounded.

Religion, though, remains a no-go area for them because of their unshakable beliefs; Sam believes in the existence of God and Jesus Christ and Hally is an atheist, although he constantly swears on Jesus and God.

However, even though Sam teaches Hally about life’s trials and tribulations, punctuated by hope through his role play as a father figure to him, he fails to realise that the metaphorical dance without collisions that he dreams of, is only a figment of his imagination; because the world lacks the music and willpower to make such a dance a success because of the different neuroses that shape individual experiences.

As Horney (1950) posits, neurosis is a compulsive response to a situation which the individual fails to understand. Hally, like Sam and Willie, scantily understands that hate is neither race conscious, nor age conscious and that neurosis has a way of obscuring individual vision.

He has never known his father in the strict sense of the word, because of his drinking habits and the fact that he is a cripple. His mother, who seems to be drawn into her business, also places a wedge between her son and her husband’s spaces on the one hand; and between Hally and “the boys”, Willie and Sam, by constantly reminding him that he should not be too familiar with them because they are black, on the other.

Horney (1950) proposes that a child’s interpretation of the world is shaped by her or his environment as illustrated in the following: “When summarised they all boil down to the fact that people in the environment are too wrapped up in their own neuroses to be able to love the child, or even to conceive of him as the particular individual he is; their attitudes towards him are determined by their own neurotic responses” (Horney, 1950: 18). At a tender age, Hally is thrown into a society that has its own problems to deal with.

As everyone collides against each other Hally is thrown at the deep end and, consequently, he struggles to locate his biography in the national discourse that pits blacks against whites. His father pushes him closer to Sam because of the ghosts that haunt his own social and marital base. His escape behaviour through rebellious alienation to Sam and Willie, food and books somehow questions the nature of life itself and Man’s purpose.

Love does not seem to exist between Hally’s parents, who are white, and between his father and himself. In the end he is so angry with his father that he doesn’t want him to be discharged from hospital. Sam and Willie, who are in their mid-40s, are not married, although they have “dancing” partners and hope to change the status quo.

As Hally struggles to find the source of his anger and hatred, he unleashes a tirade at his absent father much to the chagrin of Sam, who reprimands him.

Reality dawns on the characters that the dance of vision is only a fluke because they are in South Africa and the year is 1950; the black man (boy) has to be reminded of his place.

Despite their differences, Hally and his father share a biological line which places them above “niggers”, whose “arses” are “not fair”, hence, Sam has to henceforth call the white boy “Master Harold, like Willie”.

In the ensuing exchange of vitriol, Sam bares his backside to Hally so that he sees for himself that it is not fair, and the boy retaliates by spitting in the man’s face “like (he) was a dog”.

A ball of conflicting emotions, Hally abruptly sails home to his father, leaving Sam and Willie clinging to the dream of a flawless ballroom dance with individuals romantically “dancing their way to a happy ending” in the storms that shape their existence.

So much for a hate-free world, where the elements; love, harmony and friendship are not premised on race.

Comments