When one man’s meat is another man’s poison

David Mungoshi Shelling The Nuts—

UNANIMITY on all planes of human affairs is an incorrigible myth! Dichotomy and contradiction are the very stuff that life is built on.

There is always some kind of antipathy or opposition to most things, even where simple choices are to be made.

That is why people of Nguni stock have a somewhat amusing but wise saying: Zala abantu ziye ebantwini. Akukho ntombi yaqom’inyamazana (Girls turn down some men, but go on to love other men. No girl has ever been promised to an animal).

The proverb is a throwback to times when the doctrine of sexism was not yet enunciated. In those far-off days the word “man” was generic. It meant both male and female. Things have since changed and done so quite drastically too. Women now have identity cards for a start, and are no longer perpetual minors in the land of their birth.

What I am driving at here is the fact that contradictions are normal and natural. In fact, they are healthy and necessary.

People must agree sometimes and also disagree sometimes. Above all, they must agree to disagree. Take for instance the matter in the audio recording that is doing the rounds on social media.

Comrade Joseph Chinotimba arguing in Parliament that since our Warriors did not last very long in Gabon where success would have meant a whole month’s stay, it is obvious that not all the money budgeted for certain expenses relating to accommodation and subsistence has been used. What Cde Chinoz says makes accounting sense. Money left unused must be returned. That is a very sound principle. The unspoken text in the Honourable MP’s words is not hard to determine.

He fears that the money might somehow disappear. After all miracles are common in Zimbabwe these days. Corruption in the society, Mapfumo once lamented in his reggae piece that made waves in the country.

Perhaps I have digressed somewhat, but perhaps not. There are those who will vouchsafe for what they call positive corruption. While this kind of corruption is corruption nevertheless, those who hold it as an ideal swear by its positive results.

We are talking about the variety of choice and direction in human affairs. This is aptly put by the English proverb that says one man’s meat is another man’s poison.

This may not be the literal truth but is true, nevertheless. A son of my aunt was famous or notorious, depending on which way you want to look at it, for his insatiable appetite for anything that had meat and could be cooked on a crackling wood fire at that camp fire of his —“pachivara” or “padare”.

He was quite generous with his delicacies, but only those who did not mind what they ate allowed themselves to be entertained by this nephew of mine. I am here using the Shona kinship system.

My aunt’s son or daughter is my nephew or niece respectively. To get back to our little talk. The long and the short of it is the man’s madam boycotted all the utensils that her husband used. That was when the rumours began to fly about cats and dogs, snakes, monitor lizards and ugly crows (makunguwo/amawabayi), anything that could be salted and seasoned. The poor woman did not wish to be painted with the same brush as her meat-crazed lord and master. The things that happen under God’s heaven!

If we keep to the cuisine theme and keep talking about what people eat, we should come up with some interesting analogies and contrasts. People who come from Zaka and Bikita in Zimbabwe are renowned for being so brave as to eat a fowl-smelling beetle with a more than savoury taste.

When you eat this delicacy you weep like someone who has just peeled a lot of onions. Harurwa! Some are already frowning and saying yuck, but others are decidedly drooling. To them it’s a king’s dish, but that is something that the uninitiated can never hope to understand.

In our scenic Eastern Highlands, there is a expanse of land where people eat the toad, that scaly, pimply fellow with the bobbing Adam’s apple. He/she can produce a frightfully deep noise from his throat.

If you hear its sound on a moonless night you get a sense of the numinous, that is, your hair stands on end and you could swear that there is a malevolent presence lurking in the shadows. The clawed toad (dzetse/idlamedlu) is quite a sumptuous dish for some, no matter how others may see it.

Sometime in 1989 I went on a visit to Kinshasa in Mobutu’s Zaire and had a few opportunities to walk around the city but mostly in the company of a guide. They were very suspicious in Kinshasa in those days. A member of our visiting party was arrested for speaking in English.

He was taken to a police station and accused of being a spy. The guide and the guy’s passport finally convinced the police that there was no malice intended. The guide warned us to be circumspect in our conversations. According to him, Mobutu could hear everything that everyone said; he had special powerful machines for doing that.

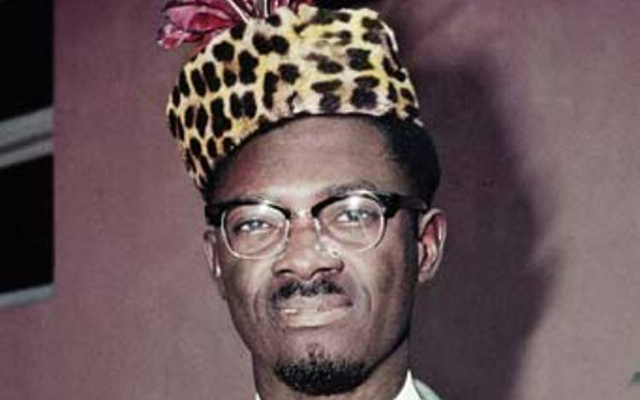

I wondered why they did not alter the Lord’s Prayer to “Our Father Mobutu, who art in Kinshasa. . . ” It goes without saying that I had neither respect nor sympathy for the tin-pot ruler who slowed down the African revolution by aiding and abetting the killing of Patrice Emile Lumumba, and later, Lumumba’s Minister of Education, young Pierre Mulele.

That whole unfortunate business can be explained in the words of our sometimes cynical English proverb.

Lumumba must have been offering a political cuisine that was poison to surrogate politicians like Joseph Mobutu and Moise Tshombe, the secessionist Katanga rebel that brought the curse of endless wars and conflicts to the Congo.

Anyway, while in Kinshasa, we visited the market, a vast concern where you can buy anything from food to clothes and all sorts of trinkets and accessories. It was said at the time that any given moment you were likely to have up to 5 000 or more people transacting there.

Our small group of Zimbabweans came to a stall where a woman had on display, dried monkey for sale. We were made to understand that it was a delicacy in these parts. But its gnarled dried fingers and smoked face was too much for one of our party. Someone reminded her that one man’s meat was another man’s poison.

I was quite sure that if someone from Kinshasa were to visit us they would find something in our diet more than a little disgusting. But even as I was thinking this way, a picture from the past came slowly stirring in my memory; the grass on the school football pitch mown almost to the ground by millions of armyworms wriggling all over the playground.

In Bulawayo we called the armyworm ‘imhogoyi’ a word that even its sound was derogatory. But guess what? There were some among us in locations (now the ghettos) who regarded the armyworm invasion as a God-send. They took platefuls of the despicable worm home to cook and eat. And they were not bothered by the sneers and the head-shakes.

In more charitable moments my reflections suggested that while many people regarded the mopani worms (madora/amacimbi) as the very height of sumptuous cuisines, some would want our heads examined for eating such creepy crawlies. They of course do not appreciate just how delicious and appetising the mopani worms can be properly cooked with tomatoes and onions and sprinkled with chilli sauce. Using them as delectable relish you can “finish” a whole mountain of sadza.

Whatever the case may be in specific individual cases, that English proverb remains unchallenged. Indeed, one man’s meat is another man’s poison, and tastes sometimes do change with perceived upward mobility.

When people think they have come up in the world they do crazy things, like Kenny Kunene eating so-called sushi, a dish of raw fish eaten off the belly of a half-dressed girl lying on her back in some pretentious night club down South.

Many people eat crocodile meat these days without even thinking about it. Yet there was a time when you could not have spoken of having supped on crocodile tail. Your family would most likely have taken you to a diviner to have your head read.

But, lo and behold, crocodile tail is the exotic dish that together with bungee jumping at the bridge, and a boat cruise on the Zambezi above the Victoria Falls, we use to bring in tourists from foreign markets.

They come in their droves to stand in wonder in the spray of one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

In Mutoko they might, if you are lucky, serve you the rock chicken (hukurutombo) a delicious monitor lizard.

David Mungoshi is an applied linguist, social commentator, poet and novelist.

Comments