What a sick racist lot

Robson Sharuko Senior Sports Editor

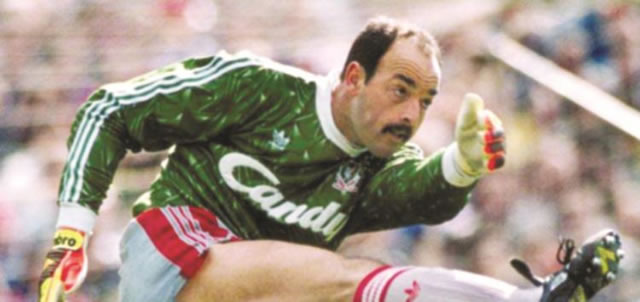

BRUCE GROBBELAAR has lifted the lid on the sickening degree of racism that was rampant when he was growing up as a kid in Rhodesia and claims that his dance with football helped him understand that black people were not necessarily inferior. The finest Zimbabwe goalkeeper of all-time, who attained greatness during a golden spell at Liverpool and was part of the immortal Dream Team, makes startling revelations, about how racism was planted into their vulnerable minds at school, in a new book that has been released in England.

Grobbelaar’s revelations are contained in the book, Red Machine, by Simon Hughes, which is about the untold stories of the dressing room of the iconic Liverpool team of the 1980s which was widely acknowledged as the best football team in the world.

Extracts from the book have been published by British newspaper, Daily Telegraph, and the Jungle Man’s frank, yet disturbing revelations, probably explain why racism has been a big part of the soul of mainstream sporting disciplines like cricket and rugby in this country.

Zimbabwe Cricket continues to suffer sporadic attacks from some racist elements, still opposed to the transformation that happened in the sport, to turn it from just a haven for a minority section of the society into a truly national sporting discipline.

The 56-year-old Grobbelaar, who was born in Durban, South Africa, but grew up in Zimbabwe after arriving with his family here when he was only two, said they were taught, from an early age at school, that the whites were a superior race when compared to their black counterparts in Rhodesia.

“From an early age, we were taught in school that there was a fundamental difference between black people and white people – that we were superior,” Grobbelaar sensationally reveals in the book, Red Machine, whose foreword was written by current Liverpool skipper, Steve Gerrard.

According to the Red Machine, Grobbelaar’s view of black people started changing when he decided to join Bulawayo giants Highlanders, then a team made up predominantly of black players and supported by black fans, in the 1970s.

And his dance with Bosso did not only change the Jungle Man, it also helped his mother begin to see black people differently.

The Bosso leadership, according to Grobbelaar, offered him a bizarre signing-on present to put pen to paper and become a Highlanders’ player.

“They offered me a cow, a goat and a sheep,” the former Zimbabwe international ’keeper says in Red Machine.

“Then the second question was whether we wanted them alive or to collect them at the abattoir. We took the goat alive and the other two dead.

“My mum went with me to pick them up and for the first time genuinely started to talk with the blacks. She realised they were just as normal as us.”

But Grobbelaar’s football career was interrupted when he was drafted into the Rhodesian army to fight the freedom fighters in the war of liberation that would eventually bring Zimbabwe’s independence.

The former Warriors ’keeper also reveals the racist garbage they were fed, to intensify their hatred of the black freedom fighters, who were described in their drills as “black bastards”.

“How can I forget or forgive myself for killing a fellow human being, even if it was in a war? I still have nightmares about it,” Grobbelaar says.

“Everything else in life seems insignificant compared to my years in the forces. During bayonet training, our superiors tried to make it more serious by making us scream, ‘I’ll kill you, you black bastard.’

“When you’re eyeball-to-eyeball with the enemy, you know that one of you is going to die. But that doesn’t make it any easier in dealing with the guilt.”

Grobbelaar claims that he was born to be “clumsy” and to clown because that’s what his surname stands for when roughly translated.

“The surname Grobbelaar is roughly translated in English from original Dutch as ‘clumsy’, so I think I was struggling from the start to rid myself of the clown tag that plagued me throughout my career,” he says.

Clowning was a big part of his game at Liverpool where he became a very successful player and the most decorated ’keeper in the history of the Anfield club.

He was also the player, closest to events on the field, when trouble erupted at Heysel Stadium in Belgium in 1984, during the European Cup final, leaving 39 Juventus fans dead and when 96 Liverpool fans perished at Hillsborough.

Grobbelaar remembers the events at Heysel.

“It was worse than witnessing what I saw in the bush. These (fans in the stands) were grown men behaving like savages,” said the retired ’keeper.

“My then mother-in-law came over for the final on the ferry, and she was one of many who were handed pamphlets by the National Front, which basically said, ‘Liverpool will not be in Europe again.’

“The NF saw Scousers as scroungers and envied Liverpool’s success on a football field. My mother-in-law said that a lot of the people handing out pamphlets had Chelsea and Millwall tattoos on their arms. People are still free now with blood on their hands.

“I travelled to one of their (NF) headquarters, just outside Slough, for a group meeting. They recognised me straight away and because I was a white guy from Rhodesia, they assumed that I was racist. So they welcomed me.

“I had a drink and tried to relax. One of the heads approached me and we got talking. I asked whether they knew anybody who was involved in Heysel and all of a sudden he went cold, said no, then walked off. He sussed me and I decided it was best I leave for my own safety.”

Grobbelaar’s rise to become one of the greatest goalkeepers of all-time has been quite a stunning tale, but the “Jungle Man” insists it’s not Hollywood stuff.

“It is very true that my story is different. You couldn’t compare it to a Hollywood story, though. No, no. In Hollywood, when you’ve made it to the top – you’re there for life,” he says.

“In the UK, people look for a way to try to knock you down. People think that because I was at Liverpool for such a long time, in a period where the club was very successful, that it was bliss all the way through.

“But at the start, because of poor performances, I received death threats. I played for the club through two stadium disasters then later was falsely accused of fixing matches. I loved my time there, but it would be a lie to say it was always a walk in the park.”

Comments