War veterans should back off

War veterans must temper their sense of entitlement by recognising the unsung heroes of the liberation struggle

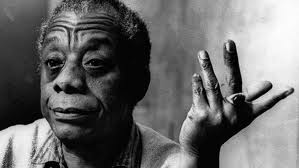

Political Mondays with Amai Jukwa

LAST week legislators were treated to inexpensive Parliamentary entertainment as Dubeko Sibanda (MDC-T) and Mandi Chimene (Zanu-PF) squared off like pompous teenagers. Sibanda took considerable exception to Chimene’s pointed finger, which NewsDay went on to dutifully describe as ‘a threatening finger’.

What large fingers these Zanu-PF legislators must have!

The subject of their quarrel was a motion on the plight of war veterans, which the MDC-T legislator heckled incessantly much to the irritation of his Zanu-PF colleague. It was pointed out that war veterans were receiving US$175 per month for their labours during the struggle, an apparently unsatisfactory sum.

War veterans for their part have complained bitterly over perceived neglect by their fellow comrades who have now joined Government. “We deserve better”.

“We fought for this country”.

The question is, do war veterans really deserve better? Are war veterans entitled to special treatment?

The answer to those questions depends on their motives for going to war.

If it were the noble draw of patriotism that sent them to war then it would stand to reason that what they did was an admirable act of grace for which no payment is required. However, if one was motivated by mercenary tendencies and an imagined bounty then Zimbabwean taxpayers must certainly cough up good money.

I’m reminded of the Libyan rebels in Benghazi demanding a greater share of the spoils because it is they that dared rise up against Gaddafi.

I’m being disingenuous. The truth lies somewhere in between.

After the war I would have expected the Government to expend great resources in ensuring war veterans had special access to education and training to allow them to enjoy a gainful existence.

This is on the reasoning that many of them had left school prematurely to join the struggle. I would similarly not object if a special fund was set aside offering war veterans modest start-up funds if they felt drawn to business, repayable of course.

However it is important to recognise the distinction between giving special help and being indebted.

Help suggests a voluntary generosity toward one already in effort; it is not a burden of responsibility for the well-being of grown men and women.

The problem is that war veterans feel they are owed financial security at the expense of everyone else.

I respectfully disagree.

Zimbabwean taxpayers do not owe war veterans a comfortable living any more than they owe the same to an orphan equally in need of State assistance.

The term ‘war veteran’ has become a term of abuse, hardly endearing.

Part of this is due to this disagreeable sense of financial entitlement regularly displayed by war veterans.

It has robbed them of the prestige and honour they rightly deserve. This is to be expected.

If you are demanding money for your services then you cannot equally claim nobility. You become something of a mercenary.

To be fair, mercenaries are far more reasonable in their expectations, content with a one-off payment.

You pay them once and they go away. However, war veterans seem to want it all, lump sum payments in the 1990’s, farms during the land reform programme and now a comfy monthly stipend. “We deserve it; we fought for this country”.

Medical doctors in Government employ currently earn us$283 for their monthly labours.

Pensioners receive less than US$70. It is against this background that we must consider the US$175 that war veterans are said to receive.

If highly skilled professionals have come to terms with our economic problems I think it’s high time those who shout the loudest patriotic slogans do the same.

Quite frankly, US$175 is a lot of money for someone who is doing no work.

I cannot accept an argument that says an impoverished citizen living in a squatter camp should stand behind war veterans in the queue for Government assistance.

Surely war veterans did not go to war to become super citizens?

If war veterans are hungry they should know that they are not alone in that hunger; it would be a lot more dignified if they lobbied Government for a broad-based safety net for all citizens so that nobody goes hungry.

It seems as though war veterans are suggesting that they should not be poor even though many other Zimbabweans are poor, that they should be insulated from poverty on the grounds that they fought the war. This is nonsense.

War veterans must temper their sense of entitlement by recognising the unsung heroes of the liberation struggle.

The war was a collective effort. Black businessmen were shot dead for supplying jeans and other materials to the fighters.

Peasants put themselves at grave risk to feed these fighters.

They slaughtered precious livestock all in the spirit of liberation. How much do they deserve?

What can we say of the many thousands that actually died in this cruel war?

Their families lost more than just breadwinners.

They lost a loved son, a brother, a sister. They did not even get a chance to bury them.

What monetary value can we attach to such loss?

Are they not entitled to a monthly financial consolation greater than those who are alive today?

War veterans are not super citizens and must accept that they too must bear with our economic circumstances. Nobody can jump the queue.

Their selfish demands for more money will bear no fruit apart from diminishing their prestige and that of the noble struggle they waged.

Ndatenda, ndini muchembere wenyu Amai Jukwa

Comments