Traditional music conquers time

Innocent Tinashe Mutero

Zimbabwe has a rich, diverse cultural heritage and her music and dance are intertwined. Implied is that the two are inseparable – there is no music without dance.

As a multi-cultural country, Zimbabwe’s traditional music genres are just as varied as the ethnic groups inhibiting the country.

Researcher Kariamu Asante argues that “one cannot discuss Zimbabwean dance as an entity when Zimbabwe contains so many different ethnic groups, each with their own particular history and sub-culture”.

However, there is consensus that the Shona and Ndebele are the two major ethnic groups of Zimbabwe with the Shona making 82 percent of the population while the Ndebele make up 14 percent of the total population.

Even though the Shona and Ndebele outnumber all the other ethnic groups, these other smaller groups continue to practice their own culture and traditions. For instance, the Shangwe have Jichi, the Kalanga have amabhiza and the Ndau identify with mhongoyo. Whereas mbakumba, jerusarema and shangara are usually identified as Shona traditional music and dances, amabhiza, amantshomane and isitshikitsha are associated with the Ndebele people.

Traditional musical instruments

A commonality in most Zimbabwean traditional music genres is that they are accompanied by the drum, known as ngoma in Shona and ingungu in IsiNdebele. The drums are just as varied as the genres and they come in different sizes and shapes. In most cases, the bigger drums are played using sticks while the smaller ones are played using open palms. There are some exceptions, however, such as the small drum played to accompany Amabhiza, which is played using one hand as the other hand will be rubbing/scratching the drum using a stick to produce an unusual screeching sound. Muchongoyo music is also accompanied by peculiar drums. These have animal skin on both ends of the drum, which are played using sticks, regardless of the size of the drum. The size of the stick is however, proportionate to the size of the drum.

Besides drums, traditional Zimbabwean music has a variety of percussive instruments, including shakers (hosho), leg rattles (magaga, magavhu and amahlayi) and wooden clappers (makwa). Mbira musicians also use chikorodzi, a notched stick scraped by another stick, as well as kanyemba, an instrument made of many bamboo strips that are stripped together and filled with small seeds for percussion.

Arguably the most famous of the Zimbabwean musical instruments is the mbira. There are several types of mbiras found in Zimbabwe, which are played during both religious and secular activities. Of the many types of mbiras found in Zimbabwe, the most common are the nhare (telephone) or mbira dzavadzimu (the ancestors’ mbira) and the nyunga-nyunga mbira. The mbira dzavadzimu has between 22 and 24 keys and is known for its ability to invoke the spirit. The nyunga-nyunga mbira is a 15-key mbira and has been widely popularised by Zimbabwe’s education sector, where it is taught from primary school up to university level. Some of the Shona language names for the range of mbiras in Zimbabwe include njari, matepe, mbira dzavandau, karimba/nyunganyunga and matepe/madebe dza mhondoro/hera.

Some traditional Zimbabwean instruments are facing the danger of extinction, such as chizambi, chipendani, tsuri, mukwati wenyere.

It is important to note that not all Zimbabwean traditional music is accompanied by instruments. Zimbabwe has traditional acapella music such as imbube, makwaira and some songs for shangwe mukwerera rain-making ceremony. Imbube is associated with the Ndebele people, while makwaira is for the Shona people. Etymology suggests that the name makwaira was derived from the word ‘choir’.

Traditional music and spirituality

Most of Zimbabwe’s traditional music and dance can be linked to the cosmology of her people. Asante forwards that “most of the Zimbabwean dances are religious or spiritual dances”. Most studies of Zimbabwean traditional music and dance also point to the fact that most Shona and Ndebele dances have a relationship with the religious and spiritual life of their people. Mhande by the Karanga people is done during the mutoro, a rain-making ritual. The Ndebele culture’s rain-making dance is called iHosana and there is a therapeutic role played by dandanda traditional music and dance, which originates from the Korekore people of Zimbabwe. The Ndebele practise of isitshikitsha seZangoma, a sacred traditional music, is for those who are traditional healers or apprentices in traditional healing. The Kalanga people of Matebeleland Province perform Amabhiza traditional music during their rain-making ceremonies.

Traditional music and contemporary social-political issues

It is not always that the traditional music of Zimbabwe is associated with religious rituals. It is also important to note that the social life of Zimbabweans is inextricably linked to their music and dancing. Zimbabwe has a rich repertoire of songs that accompany social activities. These diverse repertoires include lullabies, children’s game songs, rites of passage songs, work songs, war songs and funeral dirges, among a host of others. Simply put, Zimbabwean traditional music follows and speaks to the lifecycle of a human being.

Today Zimbabwean traditional music is also used to speak out against contemporary socio-political challenges. Community-based traditional music and dance groups have managed to deploy indigenous music to tackle the social-political malaise. These groups have a strong awareness that traditionally, music was conceived and applied to play a critical role in society, an intangible force that managed societal systems, coerced human consciousness and sanctioned certain deviations in the conduct of stable societal living.

Preserving Zimbabwean traditional music

Regardless of the profound utilitarian role that indigenous music plays in bringing about social change, it is waning in popularity. Zimbabwean traditional music faces an unhealthy future as most young people shun traditional music in favour of Western-influenced contemporary music, like the hugely popular genre known as Zim-Dancehall. This Jamaican-influenced popular youth culture therefore threatens the continued existence of Zimbabwean indigenous music as its rising popularity is juxtaposed with the ailing popularity of traditional music.

Not much is being done by the government, civil society or corporates to safeguard indigenous music.

Zimbabwe has two prestigious traditional music and dance festivals, the Jikinya dance festival and the Chibuku Neshamwari traditional dance competition. The Jikinya festival is meant for primary schools and the Chibuku NeShamwari is meant for everyone above 18 years. The festivals aim at encouraging young and old to appreciate and perform indigenous Zimbabwean dances. Though the competitions stand as the only two reliable national performance platforms, they are isolated events. There are no processes or programmes set up to safeguard and promote the posterity of traditional music.

Traditional music’s influence on popular music

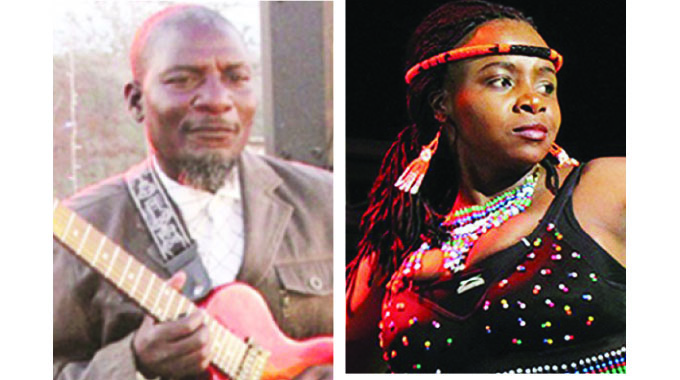

Despite the threats facing traditional music in Zimbabwe, not all hope is lost. Some mainstream popular musicians are producing music that is influenced by traditional music. Jah Prayzah for example, is arguably the man-of-the-moment in Zimbabwe’s pop music arena. He uses mbira and marimba in his music. One of Jah Prayzah’s most popular tracks, “Machembere” from his 2013 album “Tsviriyo”, is played on the traditional mbira mode known as vamudhara. Other artists such as the internationally acclaimed Oliver Mtukudzi make music influenced by traditional genres. Tracks such as “Tozeza Baba” are influenced by chinyambera and dinhe traditional music. The music of popular musicians such as Hope Masike and the late Chiwoniso Maraire also relies heavily on the mbira, while groups such as Mawungira eNharira and Mbira DzeNharira continue to perform traditional mbira music.

The influence of traditional music has also been seen in the church. It is a sure paradox that early missionaries demonised traditional music, but today traditional music forms the backbone of church music. The Catholic Church and most Protestant churches use the drum (ngoma), shakers (hosho), horn (hwamanda) and the whistle (pembe) in their music. The common argument for this enculturation of traditional music into church music is that it was meant to make indigenous people identify with their music and subsequently the Christian way of life. Whether this argument is real or imagined, what is factual is that Zimbabwean traditional music is indeed woven into all activities. However, it is imperative that Zimbabwe sets up institutions dedicated to preserving and promoting her traditional music, which represents an invaluable source of indigenous knowledge. – musicinafrica.net.

Comments