The search for personal space

Many elderly men move to the granary full time while the old ladies enjoy their freedom sleeping alone or with little grand children in the kitchen hut

Sekai Nzenza on Wednesday

The other day, my cousin Reuben was counting the number of single mature women who live alone in Harare. This idea came up when our friend Temba, the one who lives in the USA, and is planning to return home for Christmas, asked if there were women he could meet for conversation and good company.

Temba said, “I am not looking for a relationship per se. I just want some company sometimes. Not all the time. You see, I like my personal space.”

Personal space is a modern concept that we have adopted since we left the village and moved to the city and the Diaspora. It is a noble idea. But some of us are struggling to balance the idea of being alone sometimes and sharing communal space with other people at other times.

I was born in a very small hut in the middle of a large village compound. If you stood on top of the granite rocks where my grandmother Mbuya VaMandirowesa is now buried, the village homestead looked like mushrooms, sprouting out of the ground.

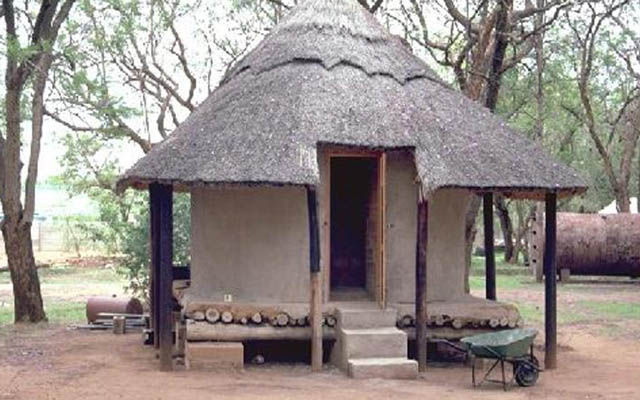

The huts looked the same, though Mbuya’s was the biggest because all ceremonies were held in that round hut. The huts were all in a row facing the granaries that were mounted on logs and four big rocks so termites would not get to our maize, millet, sorghum, groundnuts and other crops.

We slept on the reed mat in the kitchen hut while the boys shared their own round hut a little further away from us. But the other kids under three, zvindumurwa, slept with Mbuya. At that time, Mbuya no longer shared the mat with Sekuru Dickson. She said, at her age, personal space was very important to her.

Sekuru often did the rounds moving from one bedroom hut of one wife to the other. He had four wives. But, on some occasions, he declared loudly that he was too old to have anyone near him on the mat at night. He wanted freedom to enjoy own personal space. Vaida kurara vakasunguka. After that public announcement in the middle of the village courtyard, we saw Sekuru grab one old blanket and climb into the hozi or the granary.

We heard him snoring. But something made Sekuru change his mind so often. He would still go back and share the mat with his wives.

Sekuru was not the only old man who left the marital mat and slept alone sharing the granary with the hungry rats and grain-eating insects. No. Many elderly men moved to the granary full time while the old ladies enjoyed their freedom sleeping alone or with little grand children in the kitchen hut.

Together with other village girls, we shared the kitchen hut space and slept like sardines packed in a tin. It was hard to turn or to sleep on your front or your stomach. One cousin called Chipo was a bed wetter or should I say mat wetter.

We felt the warm urine around us did not move. After a while, it felt cold and smelly. In the morning we inspected how wet we were. Chipo denied mat wetting, but we all knew she was the one. Mbuya gave her some roots to chew so that she would stop her bladder from letting loose each time she fell asleep. But the roots did not help. Chipo still wet herself and us as well.

Chipo needs her own room, we said. But Mbuya said it was not possible to isolate one child from the others.

Besides, there was no room. We should be patient with Chipo. One day the mat wetting would stop because it had to. A mat wetting girl was going to be a big embarrassment to her future husband. Then one day my mother announced that we were moving from the main village compound because it was too crowded.

She had already hired men to make the bricks and a corrugated iron-roofed house with plenty of space was going to be built on the foothills of the mountain, a few kilometres from the valley where everyone lived. Mbuya said my mother was mad. There were hyenas, jackals, snakes, and several scary night creatures near the hills where my mother wanted to live.

A leopard had been spotted on two or three occasions. Besides, the witches were known to gather at the muchakata tree near the foothills every night before going on their night errands of witchcraft.

Mbuya said no, everyone was going to stay in village homestead. There was no corrugated ironed-roofed house in the area at all and why should my mother have the first one built?

A family should always live, work, eat, sleep and eat together. That was the way it had always been. In those days, the evening meals of sadza and vegetables or meat were cooked by women in their own individual huts. Then each woman took her food to the dare, the men´s place.

All the plates of covered food were presented to Sekuru and all the other male elders and boys. They tasted each dish and ate which ever dish they enjoyed the most. A bad cook endured the embarrassment of the whole village compound. We girls ate in out mother’s hut or with Mbuya.

A plate of food was shared by three or more children, depending on their ages. The oldest child picked a piece of meat from the plate first and the youngest child picked last.

The oldest kids left the last one or two morsels of food, so the youngest child could eat the rest of the food alone. It was a communal life of sharing food and sharing space.

When the bricks for our house were ready, we carried them on our little heads to the place on the foothills where the four-bedroomed houses with a dining room and a verandah was to be built. My mother’s brother, Sekuru Cornelius Bako, the builder, came to live with us and he laid the foundations of the first corrugated iron-roofed house in our area.

After a few months, the house was complete and so was the kitchen hut next to it. My two older sisters had their own small round hut, while five of us slept together in one room. Two slept on the single bed and three on the floor. It was crowded. And yet, we did not complain about space. We were just happy to sleep in a corrugated iron -roofed house.

We could hear the sound of rain. We placed buckets and dishes to catch the rain falling from the iron roof. Then we poured that water into clay pots and it was our drinking water.

We grew up in confined small spaces. But we did not notice this until we left, got educated, found jobs, made money and started building our own mansions in the city. When some of us look back to that life in the village, where we shared personal space with others, pulling one blanket to cover our skinny bodies while sleeping on the floor, we are sometimes filled with shame. That is a past life we do not want to be associated with.

Those of us who made enough money in the big city or in the Diaspora told ourselves that our own children will have modern and comfortable space than we did not have while growing up. The child brought up in the city will have his or her own bunk bed.

Then move on to his or her own room as a teenager. He can close the door, watch television, play video games, explore the Internet and do as he pleases. He can watch what is meant for adults only and nobody cannot stop him.

If you want to go to his room, you have to knock because you are entering his private space. The same teenager will then leave the mansion in Zimbabwe and study overseas where he will have his own room.

He will leave his parents alone in the now quite common six or more bedroomed house with many toilets, showers, bath tubs, living rooms, dining rooms, a games room, TV rooms, and a cottage for visitors who never come.

Meanwhile, some of the parents who still have connections to the village like me, have built houses in the village. They will visit it once or twice a year. Most times, the mansion stands as a lonely testimony to how we have moved from confined village hut spaces to large bedrooms.

We grew up in the village with so many people around us. There was laughter and shared pain. These days, some of us live alone. But, are we happier alone? Are we happier with so much unshared space?

- Dr Sekai Nzenza is writer and cultural critic.

Comments