The politics of definitions

From its inception to its tabling at the UN Security Council, Resolution 1973 was written regime change all over it, and the Resolution itself spelt out clearly the intention of military intervention in Libya, and by mere historical logic any military intervention involving Nato must have something to do with political assassinations, and Zuma was supposed to know this regardless of his limitations in knowledge of international affairs.

Instead, he did not believe any of this when he instructed his government to vote for the resolution, only to have his blinded sense of judgement suddenly opened when just about everyone was outrageously protesting against the Western murderous acts in Libya, not least members of his ANC party in South Africa.

Zuma followed the scandalous Libya blunder by needlessly embarking on a vicious persecution streak against the ANC Youth League leadership after accusing Julius Malema of being too close to Zanu-PF in Zimbabwe, of being too hostile to Ian Khama’s government in Botswana, of being too radical in his call for nationalisation of mines in South Africa, as well as for his radical call for redistribution of land.

President Jacob Zuma audaciously ensured the expulsion of the ANC Youth League leadership from the ANC, creating for himself the political hot bomb likely to explode right in his face at the December 2012 Mangaung Elective Conference, where he faces almost certain defeat. In 2011 President Zuma mischievously delivered to Sadc in Livingstone Zambia a slightly amended document from Morgan Tsvangirai and he tried to mislead the regional body into believing it was his personal report on the political goings-on in Zimbabwe.

He had just met Morgan Tsvangirai at a village somewhere in South Africa, where the two shared goat meat as they celebrated some traditional ceremony to do with one of President Zuma’s numerous children. The encounter ended with Tsvangirai handing over the ill-fated document to Zuma.

The document drew the ire of Zanu-PF, and subsequently the Livingstone Communiqué derived from this document had to be shelved as it was overtaken by events in subsequent Sadc summits.

As if this was not enough, Zuma recently made himself an activist in the affairs of a Zimbabwean political party disputably led by his in-law Welshman Ncube, pushing hard for the recognition of Ncube as the representative of this one of the MDC formations in Zimbabwe’s inclusive Government.

This was all despite contrary views from both President Mugabe and Morgan Tsvangirai, who have both maintained that Arthur Mutambara remains the representative of the MDC formation despite the power struggles within the party. After messing up the Zimbabwean issue in Maputo, Zuma had to rush back to South Africa to sanitise the brutal acts of South Africa’s police force when they blatantly massacred 34 striking miners at Lonmin Mine in Marikana.

He regretted the deaths while blaming “violence,” and not the trigger-happy carefree police officers for the reckless and ruthless murdering of this group of miners.

Zuma failed to address the miners because he visited the mine during the night, for reasons best known to his handlers, leaving the limelight to the ousted ANC Youth League President Julius Malema, who addressed the miners to much applause. The President also failed to attend the memorial service for the slain miners, apparently out of fear of being outshined by Julius Malema.

Then the unbelievable happened. South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority decided to charge 274 miners with the murder of their colleagues, going ahead to charge another 78 wounded and hospitalised miners for attempting to murder themselves.

The entire group was also charged with public violence. This was all done in the name of a long-forgotten apartheid piece of legislation that covered something called “common purpose.”

After an outrageous protest from human rights activists across the globe, the murder charges were withdrawn, although the other charges still remain. Many have blamed the apartheid law of “common purpose” for the fate of the miners being prosecuted in South Africa.

But the law itself is just one of too many examples of how mere definitions have been used by those in power to oppress weaker peoples and minority groups.

In this case the racist white rulers of apartheid South Africa defined “common purpose” to mean “forcing us to kill you,” and in this sense any group of protesters would be deemed the murderers of their colleagues or even themselves if any people were shot down in an effort to thwart that protest.

If you were wounded and survived the bullets you would be charged with attempting to murder yourself.

The perpetrators would be exonerated while the victims would instantly be converted by a mere definition to being the perpetrators, and jailed for it.

One can look at the people who declared the war on terrorism and see what they say terrorism is. There is an official definition in the United States Army manuals. It is defined as “the calculated use of violence or the threat of violence to attain goals that are political, religious or ideological in nature . . . through intimidation, coercion or instilling fear.”

That definition sounds simple and straightforward, and even credible and appropriate. One may wonder why we are constantly reminded that defining terrorism is a vexing and complex exercise, but it is not too hard to get an explanation for this.

The official definition is unusable for two main reasons. Firstly, that definition is a very close description of government policy related to armed conflict and defence across the world. We are just often told that when governments carry it out it is called low-intensity conflict or counter-terror, or even democratisation.

The other reason one cannot use that definition is that it gives the wrong answers as to who the real terrorists are, and radically so too. When Nato forms an alliance with Al-Qaeda to intensify a civil war in Libya, killing tens of thousands of innocent civilians in the process, all to remove the incumbent Libyan government, it becomes very difficult to use the official definition of terrorism, and inevitably the official definition has to be dropped, and the logical step is to begin to search for some kind of sophisticated definition that will give the right answers; as in making the victims themselves look like the terrorists.

Part of this redefining process will mean the media will have to do such ludicrous things like calling dangerously armed Benghazi rebels, or Syrian rebels “unarmed civilians,” or even “innocent civilians.”

It is hard to succeed in misleading a generation of today’s technology, very hard. This is why we are reminded that terrorism has become such a complicated topic and that big minds are wrestling with the complex matters of this head-cracking topic. In simple lexicon they are finding it hard to deceive the people.

Fortunately a solution has been found to this complex problem. As Noam Chomsky wrote in the book “Media Control,” the solution “is to define terrorism as the terrorism that they carry out against us, whoever we happen to be.”

It does not matter where you are in the world; this has become the standard norm for governments. It has become the universal practice in journalism and in scholarship. In the West the standard conclusion is that Westerners are the main victims of terrorism, and that terrorism is a weapon of the weak, that it is a weapon of unthinking Islamists and so on and so forth.

The official definition of terrorism points to the strong as those capable of carrying out terror, but once you begin to understand that “terrorism” just means the terrorism they carry out against us, and you live in a powerful Western country, then automatically the definition begins to point at the weak as the only ones capable of using the weapon of terrorism.

George W. Bush and Tony Blair’s outrageous terror acts in Iraq read like countertenor in Western textbooks, but the arrest of a Nigerian youngster caught playing strange games with perfumes in a mid-flight plane is what reads like real terrorism to almost everyone.

September 11 and the July 7 London bombings make good historical case studies of terror acts while the Nato massacres of 50 000 Libyans easily passes for freedom fighting. Definitions play the distinctive role of shaping public opinion.

The deaths of less than a dozen white commercial farmers as a result of forceful land occupation by landless Zimbabweans goes down in Western history as an egregious murderous act of lawlessness while the massacre of 34 striking miners in South Africa easily passes for a heroic law and order maintenance act by the South African police, especially in the view of white South Africans.

When Britain’s Admiral Sir Michael Boyce said in 2001 that Britain would continue their attack against Afghanistan “until they get the leadership changed,” this was a clear illustration of the textbook definition of international terrorism according to the official definition.

However, Boyce logic was elevated to the noble levels of democratisation, and up to now that act of terror carries the noble tag of good Westerners shedding their own blood for the good of Afghans, fighting so hard in the mountains of Afghanistan just that the people of Afghanistan may know the sweetness of democracy. That is supposed to make sense even in international affairs.

We Zimbabweans must count ourselves very lucky that we are counted among the top listed on the register of people prioritised for democratisation by Western powers. We must attack relentlessly the unthankful lot among us who vainly make outrageous claims that Western countries want our natural resources, or that they want to effect regime change in our country so that they can use a puppet regime to perpetuate Western hegemony over our national affairs.

The people holding these views are delaying democracy to our nation, failing so terribly to understand the importance of good Westerners to our cause, even notoriously allowing the Chinese to make inroads into our economy.

Our own Prime Minister is convinced that without appeasing Western investors there cannot be meaningful employment in Zimbabwe, and we are meant to define Western meddling in the affairs of our country as a matter of goodwill meant to liberate us from our own evil selves, and to revive our economy.

Democracy to us has been reduced to matters of ensuring procedural rights while negating or ignoring substantial rights, and we are supposed to take this in good faith hoping that those enjoying substantial rights on our collective behalf can reward us with such benefits as jobs and other meagre social benefits in an anticipated capitalist filter-down effect.

Zimbabwe, we are one and together we will overcome.

It is homeland or death!

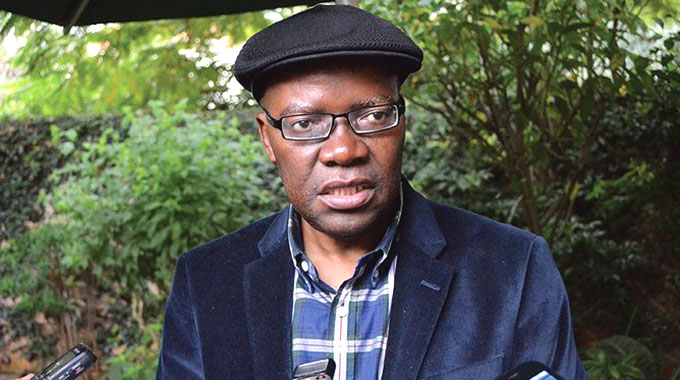

Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia.

Comments