The permanent crisis of egalitarian politics

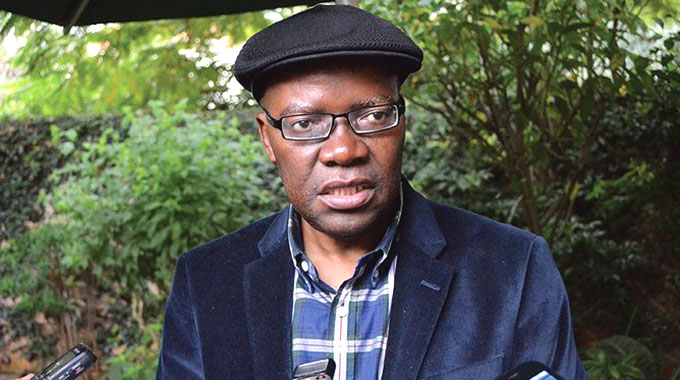

Reason Wafawarowa on Thursday

AFRICAN contemporary populism is not too difficult to figure out. Whether it is coming from the left or from the right, from governing parties or from the opposition; the reigning theme is always theft: the ruling party is stealing the people’s freedom, the government is looting resources, the imperialists are stealing the country’s wealth, the Chinese are stealing African resources, the corporations are stealing from the country, the Nigerians are stealing our businesses, the foreigners are stealing jobs and so on and so forth.

Populism prescribes illegitimate expropriation of value as the major source of grievance among the masses, and many politicians in Africa would rather give the voter a reason to protest against a competing politician than give a cause for which they themselves must be elected.

Many Zimbabweans believe voting for Tsvangirai is a way of protesting against Zanu-PF, and they have no idea what the opposition politician has to offer to the country. It does not look like Tsvangirai himself knows any better.

The Zimbabwean media recently rallied a polarised Zimbabwean community to unanimity when the mainstream media exposed egregious acts of corruption in State-owned enterprises. When you embark on an expose of those stealing from the public you inevitably start striding on the sensational wave of populism. You give people something to protest about.

The MDC was largely founded on the rhetoric that Zanu-PF was stealing from the people of Zimbabwe, stealing the country’s wealth, stealing the people’s freedom, stealing posterity’s destiny and so on and so forth. That rhetoric was significantly popular with students and the urban youths.

We tend to believe that some rogue characters among our political elites are blatantly violating the social ethic of accountability, and not many times do we pause to think that that the social order that once gave us the perceived yesteryear accountability is itself breaking down and giving birth to the rogue characters we consider the major problem in our society.

When we look at the biting economic situation in Zimbabwe, some among the ruling elites are expressly convinced that Western economic sanctions are the sole attribute to which the scourge of economic collapse must be connected.

It makes good politics to tell the suffering masses that some rogue Western rulers have stolen their happiness through the deadly effect of ruinous economic sanctions, but no sane person will believe that Zimbabwe purely runs on lack of Western economic sanctions – the presence of which bringing a total halt to the entire country machinery.

The resentment of Zanu-PF by many of Zimbabwe’s urban dwellers in the first decade of the millennium must not be seen as a response to perpetual dictatorship or theft, as attributed to the party’s leadership by political rivals from the opposition. Rather it must be seen in the context of the existential challenge caused by the post-land reform economic status.

Many of our students are convinced that they did what was expected of them – study seriously and work hard so that the country can reward them with well-paying jobs after graduating. Many of our employed people feel they adequately play their role by working hard in their places of work, and they expect rewards they see as commensurate to their efforts. This is fair enough.

When people are convinced that they have taken full responsibility over what is expected of them, and that nothing has been achieved from such effort, the natural tendency is to assume that it is all to do with someone cheating, and in our case the easy assumption is to blame the sitting Government.

Populism cannot grasp personal responsibility. It thrives on passing blame on a perceived or real enemy. Populism single-sidedly mobilises labour against employers, advocates vigorously against free flow of capital, resolutely stands against profiteering, can push for currency manipulation, preaches expropriation, advocates for state retaliation against perceived exploiters, pushes for protectionism, it celebrates the local and derides the foreign. In fact, populism if unchecked can easily strengthen the source of its own woes.

When a populist government embarks on an unsustainable expenditure budget it involuntarily strengthens the very source of its woes.

From a moral point of view we generally view rightwing populism of hierarchy, exclusion, inequality, repression and profiteering as more repugnant than the socialist/communist populism of the left, things like increasing income for the poor, controlling prices and so on.

Populists have this gnostic view of the world where the populist side represents the divine, and the contenting side is viewed as demonic. This explains the evil capitalist – holy socialist,or the evil communist – holy capitalist approach to global politics.

We also often see this approach in the West’s much-hailed democratisation rhetoric. It is always the holy Western-endorsed democracies versus the evil Western-condemned dictatorships.

The Australian-based so-called Zimbabwe Information Centre is resolutely convinced that it stands on holy ground on matters of Zimbabwe’s democracy, and the group believes Zanu-PF and President Mugabe are evil by definition.

Anyone that may not agree with this position becomes evil and is labelled an “enemy of the Zimbabwean people,” or “an agent of the regime,” of course as defined by the self-confessed democrats.

Perhaps it is time we must understand that modernity is monistic, and that the contradictions populism understands as good and evil are in fact realistic features of the socio-economic structures of modern day society.

Empowerment of the indigenous Zimbabwean cannot eradicate the power of foreign capital, just like giving of land to the poor masses cannot annihilate commercialised profit making in agriculture.

Capital cannot annihilate the poor masses, and the poor masses can never annihilate capital. Foreign investment cannot eradicate the economic empowerment of the local people, just like affirmative promotion of local investors cannot abolish foreign investment.

The unchecked triumph of one side will inevitably be overturned in the next crisis, the way the skewed capitalist white land ownership was overturned in Zimbabwe in 2000.

Land redistribution designed solely to annihilate capitalist land ownership cannot succeed. It gets overturned in the crisis that follows, and this is why capitalist ownership of land is slowly creeping back into Zimbabwe’s agrarian sector – never mind the colour of the new owner of the capital.

No matter how strong one side of each antinomy becomes, it can never annihilate its opposite because the nature of modernity constantly reproduces each opposition.

We hear Zimbabwe is revising its indigenisation policy, and by every indication the changes are designed to attract and accommodate capital investment from the traditional foreign quarters, the very forces from whom the policy seeks to protect marginalised locals.

It does not matter what the rhetoric around the indigenisation policy was or is, the concept cannot and will not annihilate foreign investment in the country. Any attempt to do so will create a crisis that will end up inviting more foreign capital than there was before the indigenisation policy was even conceived, and we have already started to see the signs of such a crisis.

The populist politician might have ambitiously sold to us the idea that capital must be overthrown in order to economically empower Zimbabweans. We cannot economically empower Zimbabweans by merely eliminating capital. That can only create a crisis likely to be resolved by the unmitigated return of the same capital, perhaps in a more vicious manner.

The antinomies of African modernity cannot be entirely resolved with today’s justice extinguishing the injustice of our colonial past, much as that idea sounds logical and palatable to the ear.

We have totally failed to get rid of our colonial borders, we have failed to get rid of the legacy of colonial civilisation, including our telling pride in the use of the English language, and we cannot possibly think that the injustice of foreign investment is any easier to eradicate than any of the entrenched colonial values that we have failed to deal with in our post-colonial era.

As long oppressed Africans our intense and fully warranted feelings of disgust and fury towards imperialism and neoliberalism is understandable and even admirable. However, our obsession with left-wing populism of focusing on smiting the enemy rather than imaging a new configuration of social relations that could revive our declining economies is less than helpful.

This has been the bane of the MDC in Zimbabwe. From its inception the party has intensely specialised in smiting Zanu-PF without offering any policies of its own, and the approach has created for the Western-backed party an acute existential crisis.

The problem with populism is not that it does not have ideas, or that its ideas are unsound or unfounded. Most populist ideas are fantastic in principle. The major challenge with populism is that it often does not understand the conditions that would be required to achieve its otherwise noble goals.

In Zimbabwe populism has successfully disorganised the neoliberal agenda – defeating without dispute the Western onslaught on the country’s economic landscape in the last 14 years, and completely thwarting the West’s regime change agenda.

But defeating the Western agenda has only intensified the crisis, and that is exactly what smiting the enemy without a workable alternative working-plan does.

If populism continues to grow and begins to win real victories, the real question is how it will respond when it begins to run up against the inadequacies of its own project. Let us look at our own land reform programme. To a reasonable extent the distribution phase has been successful, but how are we coping with the inadequacies of the project – among them unutilised and underutilised land, lack of inputs, monopolistic ownership of land and so on and so forth?

How are we coping with corruption in the aftermath of our popular national liberation project?

It appears like we are struggling to find the distinction between the excesses of imperial capitalism and its progressive aspects.

This leaves us in the awkward position of deriding the very thing we are hankering to harbour, belittling the very people we look up to in the shaping of our own future and destiny.

We are stuck in the permanent crisis of egalitarian politics.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia

Comments