The downside of client politics

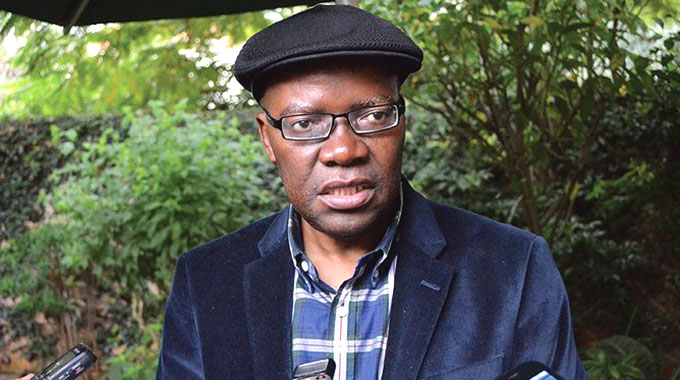

Reason Wafawarova on Thursday

IT is an onerous task to distinguish between conviction and client politics in Zimbabwe, especially given the pretentious posturing so characteristic of our competing politicians across the divide, and also the pragmatism of achieving much of the preached intentions – unbridled economic empowerment of our people on one end, and unlimited democratic freedoms for the same on the other.

Let us look at client politics as a starting point: the type of politics where an organised minority or interest group benefits at the expense of the public, or in international affairs at the expense of the dependent dominated state.

Client politics usually have a strong interaction with the dynamics of identity politics. We are hereby making reference to this notorious political argument that focuses on self-interests and perspectives of self-identified interest groups that seek to shape people’s politics in correlation to their own values and wants.

There are undeterred minority groups that would not mind an inch even if it took ransoming the whole populace just to meet their own needs.

During the colonial times we had race minority groups flagrantly shaping African politics according to their own interest, reducing all of us to economic inputs and tools of economic trade. We know too well how toady’s elites shape people’s politics in order to manufacture public consent for the pursuance of their own minority interests.

We can look at how religion has become an exigent factor in the political landscape of Nigeria today, or in those of Egypt, Iraq and Syria. Wahhabism and the Sunni-Shiite politics in the Middle East are a result of identity politics gone wrong, Wahhabism spawning radical groups like Al-Qaeda, Al-Shabaab, Boko Haram, and arguably the Muslim Brotherhood, Hezbollah and others like the Taliban.

Ethnicity has for long been the chief instigation for many murderous civil wars across Africa, just like ideology was the major force behind the Cold War. Many governments have been overthrown in history purely on the basis of competing ideologies, and we can also look at other minority social groups like gender, sexual orientation, culture and so on, and they all point to the dynamics of identity politics.

Looking back at the foundations of patron-client politics, there is this exchange between actors of unequal power and status where the more powerful, or the patron, offers protection and access to scarce resources such as land or jobs to the client, and the client in turn provides services such as labour or votes for the patron.

We have seen the incommodious chef culture wrecking havoc in Zimbabwe’s political landscape – with cantankerous political patrons getting so used to dangling scarce resources before the faces of desperate people, be it land, food aid, farming inputs, or loans for small businesses.

Crowds are literally rented to attend political rallies, and beer and such hollow handouts are often used to bribe youths into political activism.

The Mafia also runs on patron-client relations, and patron-client politics exist in a wide variety of systems across the globe, even in the so-called mature democracies.

In many developing countries it is common to find local political bosses or chiefs trading votes of their subordinate peasantry for favours received from central government, and Africa stands as an outstanding example of such politics. There are numerous instances of publicised cases of politicised aid and developmental projects.

Across the political divide in Zimbabwe we have seen this contumelious behaviour where patron-client relations readily infiltrate the bureaucratic structures of political parties, with powerful leaders seeking to place their own personal supporters in key positions.

In fact, this dishonourable racket has become Nelson Chamisa’s job description in the midst of the infighting within the demising MDC-T, and we also saw a lot of similar politics at the end of 2013 when Zanu-PF carried out its rather chaotic elections for provincial office holders. Even President Mugabe has publicly lamented the idea of certain leaders within his party claiming to own people.

Despite variations in setting, patron-client systems are guided by a common logic. They arise in hierarchical societies, where individuals and groups compete at each level of the hierarchy, but where there is scope for collaboration between those at different levels.

The chef culture in Zimbabwe does not run like slavery where the master forced his wishes down the throats of enslaved captives. Rather it is collaboration between the chefs and the subordinate party members who willingly elevate the status of superior figures in the party structures, as purely driven by the motivation to gain resource-related favours.

One would think from a Marxist perspective that there has to be class conflict in any unfair or unjust political setup. With clientelism class politics is often rendered inappropriate, not exactly because class differences and exploitation have been eliminated, but because they are so entrenched that it becomes unquestionably rational to work within their context.

The link between patron and client is often expressed in terms of personal obligations or communal solidarity. As outlined earlier, ethnicity in its myriad of forms provides a powerful vehicle for clientelism, reinforcing cross-class linkages as a basis for political preferences or affiliation. We saw how ethnicity was a determinant factor in the 2013 Kenyan election result, with the Kikuyu-Kalenjin coalition securing a Kenyatta-Ruto presidency at the expense of the CORD coalition led by Raila Odinga, a Luo.

Patron-client links thus provide a flexible and effective tool, the persistence of which is not surprising. We have seen our own indigenisation policy providing a very effective tool in shaping the politics of the youths, the politics of business-minded people and so on and so forth.

Patron-client politics extend into international relations, where the inequality of states, and their mutual need for protection and support mirrors the conditions in which they flourish in domestic politics.

The patron state provides military protection or economic aid, in exchange for which the client state offers diplomatic support or economic opportunities. Such links, which readily involve personal relationships between national leaders, likewise cut across the unequal economic relations between industrialised and underdeveloped states.

We have seen the Chinese incursion in Africa, and in exchange for the much-needed investment, many African governments have overlooked fair trade and justice, just to secure investment leading to creation of jobs for the desperate masses, mainly in order to secure periodic votes from the same people as required by democratic term limits.

In 2003 the United States drafted the so-called Bilateral Immunity Agreements to shield its citizens from prosecution at the International Criminal Court, and more than 100 countries were arm-twisted into signing these agreements, most of them mutually obliging in exchange for various forms of economic aid.

We have been victims of the menace of puppet politics in Zimbabwe, and we now know too well how our opposition politicians allowed themselves to play willing clients to patronising Western donors.

The converse of this patron-client relationship was of course the devastating economic sanctions imposed on the Zimbabwean Government and its people in the first decade of this millennium, in retaliation to the land reform programme.

The sanctions were meant to coerce compliance on the part of the weaker state, the same way powerful political elites sometimes coerce voting compliance from marginalised masses by denying them certain favours should they show any signs of non-compliance.

Clientelism nonetheless suffers crippling defects. It is inherently inefficient because it is geared to meeting particularistic rather than universal goals; jobs or development projects are allocated by patronage criteria rather than by qualification or need.

Client politics has given to us this corruption culture where state institutions tend to be staffed by politically qualified people, as opposed to being run by meritoriously proficient personnel. It appears we have come to a point where civil servants, journalists, and even churches have to mind political correctness in order to survive, and frankly the despicable trend is simply unhealthy for development.

Our independence as a country came out of conviction politics: the practice of campaigning based on a politician’s own fundamental values or ideas, rather than attempting to represent an existing consensus, or simply take positions that are popular at polls.

Our founding fathers were men of conviction, leaving behind the comfort of their homes and jobs to wage a war of attrition against the injustice of colonialism.

We know too well how the patron-client relations were torn to pieces in 2000 when we Zimbabweans decided to defy British wishes by reclaiming white-occupied arable land, in the process replacing the era of client politics at international affairs level with that of conviction politics, or so we declared.

The fundamental value of justice and equality became the determining force behind our politics of the day, and we are aware of the unpleasant immediate consequences that came with our choice – the sharp decline in agricultural production, the economic strangulation from the West, and the undermining of our efforts by our own uncommitted resettled farmers that either left the land unutilised or chose to sell government-provided inputs for a quick buck.

Client politics emphasises distribution rather than production and is often parasitic on the productive economy. This is why some resettled farmers have been lining up for farming inputs for an unbelievable decade or over. They are obsessed with a distribution spirit, and possibly allergic to the art of production.

Client politics erodes any appeal to common values while encouraging ethnic conflict or political polarity along party lines. This often leads to a pervasive cynicism as we have seen in the demeaning of national events by sections in our political community, events like the Heroes Day or the Independence Day itself.

Such political stability as client politics provides depends more on buying the support of key groups than on establishing any basis for legitimacy. The practice is simply unsustainable.

Ultimately client politics must be seen as a barrier to political development, even though its usefulness ensures that elements of clientelism persist even in the most sophisticated political systems.

Only conviction politics will provide a true platform for genuine political development leading to sustainable development – all based on true democratic tenets where more than the ballot the economy becomes the most democratised aspect of our lives.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome! It is homeland or death!

REASON WAFAWAROVA is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia.

Comments