The cry for identity in Bury me in Africa

Elliot Ziwira @ The Book Store

AFRICAN-American writer and poet, Nilene Omodele Adeoti Foxworth’s “Bury me in Africa” which was first published by Vantage Press (USA) in 1978, explores the depths one can go in search of an identity and familial roots.

Slavery, which is humanity’s worst and demeaning crime, has left in its wake a trail of broken hearts, fragmented dreams and uprooted family trees, as shiploads of people of colour were hauled to the other hemisphere of existence, where the mighty of arms takes precedence over natural justice.

The victims of this trade, running into millions as progenies and progenitors, do not only suffer the pangs of subjugation and displacement, but are also at the receiving end of racial prejudice as their yearning for an authentic identity remains void.

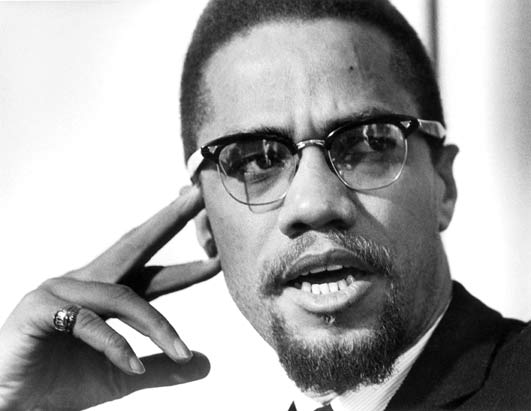

It is this identity crisis which places a burden on the Black people leaving in the diaspora as second class citizens which has prompted Malcolm X to find solace in namelessness because to him there is no form of colonialism that is as ghastly as that which robs one of a name and familial roots.

Ralph Ellison also taps into the same rationale through his use of an unnamed hero in “Invisible Man” (1952), who questions why he is black and always blue, as he gets to the bottom of “the blackness of black”.

But why should Black people be always the punch bags of other races? Is it inherent in them that they should be exploited for others’ advancement, or they are merely controlled by their own rigid mindsets?

These are the questions that Nilene Foxworth, who adopted the African name Omodele Adeoti, seeks to find answers to in “Bury me in Africa”.

The book which is a combination of prose and poetry, exploits the autobiographical mode as the fictional experience is closely intertwined with the writer’s own sojourns in search of her roots in the Motherland, Africa.

The simplicity of the language used makes the experiences captured refreshingly authentic, as meanings and feelings are not compromised for artistic ambiguity.

The reader is drawn into the heart and soul of the first person singular narrator, whose authorial voice is as intense as it is ennobling.

The story “Young Brother of Dar” captures the normlessness that the narrator suffers in her attempt to reclaim her identity in Dar es Salaam, the capital city of Tanzania.

As an African living in forced exile because of slavery, she has always dreamt of finding a true identity and not to be referred to as an African — American or Negro which in all essence does not really mean anything.

In her quest to find the roots of the uprooted familial tree, she bids farewell to her husband and children, and scours the callous oceans that facilitated the displacement of her progenies, on a home bound voyage.

Colorado Springs, Colorado, in the United States of America which has become her abode “where Blacks are still innocent victims of the shrewd injustices of the imperial crocodiles,” cannot really be called home.

Upon arrival, she is thrilled by the homely atmosphere, and mesmerised by the beautiful scenery that adorns Dar-es-Salaam.

However, her momentary exuberance fades as she is short-changed by the taxi driver who charges her $20 for a $1.50 trip from the airport to the Palm Beach Hotel where she intends to book in.

As she wilts inside, she wonders why everyone seems to gape at her like a “foreigner” yet she is black and African like all of them.

She moans: “The craving I had for a warm smile and a kind word was beginning to grow sharp pains in the pit of my stomach . . .

“I moved into the other room in tears, mainly because I sensed a very unwelcome atmosphere-a feeling of not being wanted.”

She realises, however, that she is only being paranoid because the people around her are neither mean nor segregating her, but are merely responding to the whims that are usually associated with most Africa-Americans when they visit Africa, especially for the first time.

The highlights of the story hinge on her visit to the venue of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) meeting where 18 flags are hoisted to represent the countries of the delegates in attendance.

Looking at the colourful flags flapping in the breeze, the narrator feels the descending effect of a heavy stone on her heart, as she intimates: “I also had on my African attire, but suddenly began to envy the brothers and sisters around me, thinking to myself, “’Not one Black flag can I claim-wonder which flag would claim me?’”

Through the use of the stream of consciousness technique, the writer captures the baneful nature of identity crisis as she attempts to come to terms with her situation as a black person who is not totally accepted in the two hemispheres that should claim her.

She cannot call herself American because America is known to keep those of her ilk in physical, emotional and psychological bondage; she can scantly call herself African because “no flag would claim (her)”.

The inner turmoil in her brings her to the consciousness, not of her nationality, but that of her race; Black.

“The Black people’s revolutionary struggles against colonialism and depersonalisation as well as their resilient pride epitomised by the young man she coins “young brother of Dar” inspires her, as she realises that poverty is not only lack of food, clothing or shelter but lack of an identity and national pride, as is illuminated in the following: “I watched a young brother working very hard across the way.

He was indeed a likeness to my eldest son, and even though his clothes were ragged and his shoes dilapidated, he had more than I.”

He has so much more than she, because he proudly raises his country’s flag high, and his roots are firmly stack in the land of his forefathers; their land and yet she roams along for the illusive roots that can claim her. She is all too aware that it is the land that gives a people an identity and roots as she admonishes: “A people without land are like cattle on naked ground with nothing to graze-they mope around hopelessly.”

The two weeks that she spends in Tanzania are an eye opener to her for they make her resolve that she must be interred in the land of her progenies; anywhere in Africa.

Yes she might not be aware of her true nationality, or heritage, but what she knows for fact is her Blackness, for “Blackness is not voiced; it is simply understood,” and Black people belong to Africa; they are Africans.

In the poetry section titled “My Poetic Confession”, Foxworth confesses her bitter-sweet relationship with America, which she feels has robbed her of her roots and identity that she so much yearns for. Her bitterness is especially apt in the poems “America, I Have Tasted Your Bitter Wine” and “My Poetic Confession”. She is conscious of the fact that no matter how hard she may try to fit in, she remains an alien in America, and her brothers and sisters will still be stereotyped regardless of the lip service that is aired in the direction of their plight.

It is up to the Black people of the world to embrace the colonial yoke around their necks or to undo it, for indeed Africa is for Africans no matter where they are located across the globe; their heritage and inheritance will always be in the Motherland; as the revolutionary Patrice Lumumba aptly said: “We refuse assimilation because assimilation means depersonalising the African and Africa.”

Yes she may wander around in a world that alienates and attacks her person, because of the deep rooted dislike, deceit and hypocrisy inherent in humanity, but the writer/poet finds solace in the fact that she will find eternal rest in the Motherland, as the last lines of the poem “Bury Me in Africa” purvey: “Beneath a tall coconut tree/With drums playing their very best: She came home! She came home/ Yes, she came home/to rest.”

Comments