The crisis of egalitarian politics

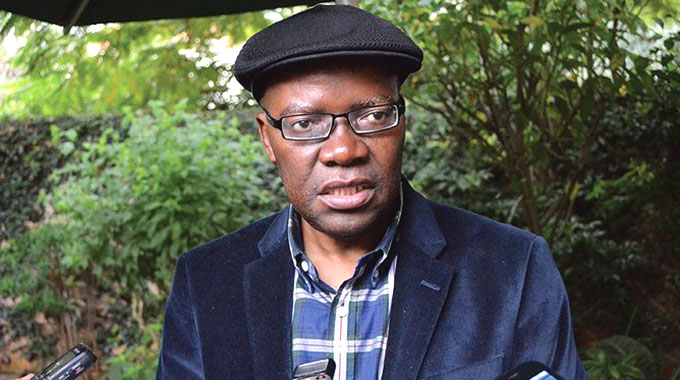

Reason Wafawarova on Monday

IN Africa, some of our politicians believe more in populism than developmental policy. We have short-sighted leaders who have made us pay a huge price that comes with failed leadership — their failed leadership. It is not too hard to figure out how populism works on the continent’s political landscape. Populism thrives on the blame game, it is a game of

excuses, scapegoating and creating imaginary enemies. The governing party often blames the opposition for having disastrous and treacherous ambitions capable of surrendering the country’s sovereignty to some unwanted monstrous foreign forces, and often the opposition’s theme and agenda is blaming Government for alleged misappropriation and looting of resources, among many other cheap slanders.

When we are not blaming each other we conveniently find it easy to create and blame perceived foreign threats, like saying the Nigerians and Chinese have taken over businesses in our country, or that the imperialists want to recolonise us, or the corporations are just about to steal every raw material we have ever possessed.

A politician is caught up in media allegations of corruption and criminal behaviour and the response is quite predictable — the allegations are the works of divisive tribalists, successionists, or any other monster concoction that may come to mind.

The rise of the EFF in South Africa has not been a meritorious one, just like we have seen with Zimbabwean opposition political parties here. The EFF is popular because Jacob Zuma looted public funds and lavished himself with luxurious constructions at his rural homestead and his sins are what Julius Malema used to found and build the EFF Empire.

It sells to suggest that apartheid imperialists are to blame for the poverty of the black African in South Africa and that assertion is not entirely baseless. However, mobilising people around the idea of resentment of wealthy white South Africans will not in itself create wealth for poor blacks in that country.

Populism prescribes illegitimate expropriation of value as the major source of grievance among the masses and many politicians in Africa would rather give the voter a reason to protest against a competing politician than give a cause for which they themselves must be elected.

Just like the MDC before it, the ZimPF leadership would rather have votes based on nationals protesting against Zanu-PF failures than they would have votes attracted by their own progressive policies, if any.

When the mainstream media gave us the Salarygate — the populism in the aftermath of the reports was breathtaking.

For once, our polarised community rallied behind The Herald, and those who were caught up in the scandalous deeds largely suffered the consequences — except that next to none were convicted or jailed. It is now 17 years of trying and failing for the Tsvangirai-led MDC-T and the party will not depart from its failed strategy of demonising Zanu-PF for votes.

Zanu-PF “stole” $15 billion of diamond money without trace we are told, the party steals elections, steals people’s freedoms, steals democracy itself and the list of accusations is longer the number of days in 17 years.

It is true that some rogue characters among our political elites are blatantly violating the social ethic of accountability, but to believe that their criminal conduct in itself will give to us a viable alternative in those fingering them is just naive.

Our socio-economic order has broken down to the extent that designated public funds can be wantonly converted to private and personal use with no remorse.

We are now told that Zinara funds can be diverted to build private tarred roads leading to the homes of those placed in charge of the funds; and that manpower development funds can now end up purchasing bicycles for villagers in remote rural places from where those placed in charge of the funds hail.

When we look at the biting economic situation in Zimbabwe, some among the ruling elites are expressly convinced that Western economic sanctions are the sole attribute to which the scourge of economic collapse must be connected. That is a very convenient way of thinking, albeit a hopelessly lazy one.

It makes good politics to tell the suffering masses that some rogue Western rulers have stolen their happiness through the deadly effect of ruinous economic sanctions, but no sane person will believe that Zimbabwe purely runs on the absence of Western economic sanctions. Even colonial Rhodesia was not that dependent on Britain. We saw Peter Mutharika rising to power in 2014 purely because Joyce Banda had reportedly looted national coffers like a woman possessed. But truly Malawi needs a lot more than protesting against a thieving government to find a way around its poverty predicament. We have seen that Mutharika has a long way to go in developing a viable developmental policy for that pauperistic country.

The existential challenge in Zimbabwe’s urban areas after the land reform programme of 2000 is quite telling. Until lately, voter resentment of Zanu-PF in urban areas was quite evident. Of course opposition politicians will maintain that the resentment is or was an expressive statement of protest against dictatorship and inhumane leadership. Such rhetoric is expected, but not exactly reasonable.

Many of our students are convinced that they did what was expected of them — study hard so that the country can reward them with well-paying jobs after graduating. That is a fair expectation and when it is not met resentment is unsurprising. Many of our employed people feel they adequately play their role by working hard in their places of work and they expect timeous rewards for their efforts. When salaries are delayed or postponed resentment is unsurprising.

The Government does have questions to answer in regards to employment creation and remuneration of its current work force. These are questions that are best answered from the finance and economic ministries than they can be answered by our law enforcement foot soldiers, much as peace is fundamental to governance.

Our opposition political forces are not seeking solutions for our country. They are taking advantage of our dire economic predicament to pursue a populist agenda — itself a vehicle to amassing the cheap vote in 2018.

Populism can single-sidedly mobilise students against the reality of a revenue-less fiscus, it can single-sidedly mobilise labour against employers, can advocate against free flow capital, it can stand against profits, can push for currency manipulation.

Populism can preach expropriation, state victimisation of minorities (like what Donald Trump has been doing), and can push for protectionism. Populism celebrates the local and derides the foreign; it says my country is better than yours because I was born here. Populism, if unchecked can cause genocides and untold suffering.

When a populist government embarks on an unsustainable expenditure budget, it involuntarily strengthens the very source of its own woes.

From a moral point of view, we generally view right wing populism of hierarchy, exclusion, inequality, repression and profiteering as more repugnant than the socialist/communist populism of the left, things like increasing income for the poor, controlling prices and so on and so forth.

Populists have this gnostic view of the world where the populist side represents the divine, and the contending side is viewed as demonic. This explains the evil capitalist — holy socialist, or the evil communist — holy capitalist approach to global politics. We also often see this approach in the West’s much-hailed democratisation rhetoric. It is always the holy Western-endorsed democracies versus the evil Western-condemned dictatorships.

We have to understand the Western burden to democratise us in the context of simplistic populism. Unthinking despots lead us and the solution for us is embracing the vote in a way given to us by the democratic West. End of tragedy.

Perhaps it is time we must understand that modernity is monistic and that the contradictions populism understands as good and evil are in fact realistic features of the socio-economic structures of modern day society.

Empowerment of the indigenous Zimbabwean cannot eradicate the power of foreign capital, just like giving of land to the poor masses cannot annihilate commercialised profit making in agriculture.

We must not only understand that, but also accept it. Capital does not and cannot necessarily annihilate the poor masses, and the poor masses can never annihilate capital. Foreign investment cannot eradicate the economic empowerment of the local people, just like affirmative promotion of local investors does not necessarily abolish foreign investment.

The unchecked triumph of one side will inevitably be overturned in the next crisis, the way the skewed capitalist white land ownership was overturned in Zimbabwe in 2000.

Land redistribution, designed solely to annihilate capitalist land ownership cannot succeed. It gets overturned in the crisis that follows and this is why capitalist ownership of land is slowly creeping back into Zimbabwe’s agrarian sector — never mind the colour of the new owner of the capital.

No matter how strong one side of each antinomy becomes, it can never annihilate its opposite because the nature of modernity constantly reproduces each opposition.

We hear Zimbabwe is revising its indigenisation policy and by every indication, the changes are designed to attract and accommodate capital investment from the traditional foreign quarters, the very forces from whom the policy seeks to protect marginalised locals.

It does not matter what the rhetoric around the indigenisation policy was or is, the concept cannot and will not annihilate foreign investment in the country.

Any attempt to do so will create a crisis that will end up inviting more foreign capital than there was before the indigenisation policy was even conceived and we have already started to see the signs of such a crisis. The populist politician might have ambitiously sold to us the idea that capital must be overthrown in order to economically empower Zimbabweans. We cannot economically empower Zimbabweans by merely eliminating capital. That can only create a crisis likely to be resolved by the unmitigated return of the same capital, perhaps in a more vicious manner.

The antinomies of African modernity cannot be entirely resolved with today’s justice extinguishing the injustice of our colonial past, much as that idea sounds logical and palatable to the ear.

We have totally failed to get rid of our colonial borders, we have failed to get rid of the legacy of colonial civilisation, including our telling pride in the use of the English language, and we cannot possibly think that the injustice of foreign investment is any easier to eradicate than any of the entrenched colonial values that we have failed to deal with in our post-colonial era.

As long-oppressed Africans, our intense and fully warranted feelings of disgust and fury towards imperialism and neoliberalism are understandable and even admirable. However our obsession with left-wing populism of focusing on smiting the enemy rather than imaging a new configuration of social relations that could revive our declining economies is less than helpful. This has been the bane of opposition politics in Zimbabwe. From the MDC to ZimPF, opposition politicians have intensely specialised in smiting Zanu-PF without offering any policies of their own and the approach has created for the Western-backed parties an acute existential crisis.

The problem with populism is not that it does not have ideas, or that its ideas are unsound or unfounded. Most populist ideas are fantastic in principle. The major challenge with populism is that it often does not understand the conditions that would be required to achieve its otherwise noble goals.

In Zimbabwe, populism has successfully disorganised the neo-liberal agenda — defeating without dispute the Western onslaught on the liberation movement Zanu-PF and completely thwarting the West’s regime change agenda.

But defeating the Western agenda has only intensified the crisis, and that is exactly what smiting the enemy without a workable alternative working-plan does. If populism continues to grow and begins to win real victories, the real question is how it will respond when it begins to run up against the inadequacies of its own project.

Let us look at our own land reform programme. To a reasonable extent, the distribution phase has been successful, but how are we coping with the inadequacies of the project — among them unutilised and underutilised land, lack of inputs, monopolistic ownership of land and so on and so forth?

How are we coping with corruption in the aftermath of our popular national liberation project? It appears like we are struggling to find the distinction between the excesses of imperial capitalism and its progressive aspects. This leaves us in the awkward position of deriding the very thing we are hankering to harbour, belittling the very people we look up to in the shaping of our own future and destiny.

We are stuck in the permanent crisis of egalitarian politics. Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia

Comments