The cook, madam’s rare friendship

Most Africans believe that cremation is disrespectful to the dead, for how does one become an ancestor when all his remains are reduced to a box of ashes?

Sekai Nzenza On Wednesday

For 35 years, Zachariah Tobaiwa cooked for a white Zimbabwean couple. During his first 10 years with them, he did not eat the food he cooked for them.

He served a three course menu that Madam had taught him to make. He cleaned the dishes and returned to the “boys’ kaya” or servants quarters where he lit a paraffin stove and cooked his own sadza, vegetables and kapenta fish.

Occasionally, he bought liver, kidneys and a piece of beef. His wife lived back here in the village. She did not visit him at all for many years.

Zachariah came back to the village when the Boss and Madam went on holidays overseas with their two children.

The twice-a-year holiday allowed VaZaka to spend time in the village for at least six weeks per year.

During those short visits, Zachariah fathered three children, two boys and a girl.

The first child, a boy, and the third, a girl, look very much like him, but the middle child looks very different from any one in the family, even his own mother.

He must have taken looks from his mother’s side of the family, or maybe from one of the relatives elsewhere because he is dark-skinned. You would almost mistake him for someone from Sudan or Senegal. In those countries, you sometimes find Africans who are tall, majestic looking and blue black. This boy is almost like that and he is a lot taller than anyone in the family. Genetics can play games like that.

After 10 years with the white family, Zachariah was still serving a three course meal then cooking and eating alone later on. Then one day Madam said he should leave some food for himself so he does not have to light the paraffin stove and cook for himself afterwards. From that time onwards, Zachariah hardly ate any sadza. He ate what he cooked for the Boss and Madam’s family.

Zachariah was no longer just an African cook but one of the family. Boss and Madam stopped calling him Zachariah. Instead, they called him Zac.

Back here in the village, we call him VaZaka vekwaJim. Although VaZaka lives several kilometres from our homestead, he is well-known around here from the time he left the village before independence to the time he returned here to live in 2008.

He was here for my mother’s kurova guva ceremony for two weeks because we are related to him.

His mother shared the same totem with my father, Mhofu — the Eland.

This means, VaZaka’s mother was my aunt and he is therefore my son.

Although he is 80 or a bit more years old now, he calls me mother, or simply VaChihera. He claps his hands to me and my sisters with enormous respect that he would give to his own mother.

I saw him come for the ceremony towards sunset, wearing a suit, a hat and a walking stick in hand. My cousin Piri was the first to see him, and grabbing my arm as she does when she is excited, she said, “Sis, remember VaZaka, the only African man from here who can cook all the European goulashes, soups, salads and desserts for white people?”

We greeted him warmly. Before the drums started, my brother Sidney, Piri and few others shared warm freshly brewed beer and roast meat with VaZaka.

For a moment, I wished someone had not asked him about his work and why he came back to the village after the economic problems of 2008 when his Madam left the country.

VaZaka sat there, drinking beer slowly and telling us about his life as a cook for 35 years. He said there were three children in Boss and Madam’s house. Two boys and one girl. The middle son was disabled physically and mentally. They kept him at Dorothy Duncan, the former whites-only home for intellectually challenged people.

The other two children went on to get degrees at the University of Rhodesia. The girl became a doctor and the boy was an engineer. Soon after independence, the girl went to London and met an English doctor. She brought him home.

They both worked at Harare Hospital and at Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals for a few years. The English guy loved his in-laws and loved Zimbabwe.

Meanwhile, the engineer son migrated to Australia where he married a Chinese girl. They hardly visited. The intellectually disabled son had a stroke and died a few years after independence.

One day the daughter and her husband announced that they were migrating to Vancouver, Canada. They left in 1990. Occasionally, they came home for the holidays and did the Mana Pools, Victoria Falls and Nyanga tours. Each time they did that, the daughter brought a present for Zac. One year she brought him a T shirt with Vancouver written on it. Zac wore the T-shirt under his khaki cook’s uniform until it had holes all over the shoulders.

Madam saw it and laughed. She said, “Zac, you have to let go of something when it’s old. Come on man, you are not that poor!” She called her daughter in Canada and asked him to send Zac another T-shirt by post.

She did.

This time the T-shirt had a picture of snow-capped mountains and people skiing on the slopes. From then on, Zac got a T-shirt from Canada once or twice a year.

His suitcase, which he says is now placed on top of the wardrobe in his corrugated roofed village house is full of some of those old T-shirts, including a very warm fleece jacket that he inherited when Boss died in 2005.

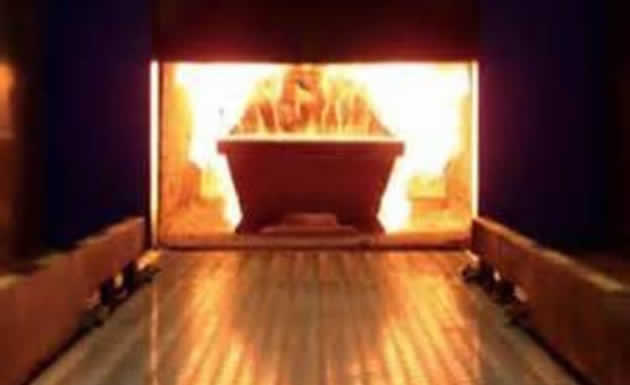

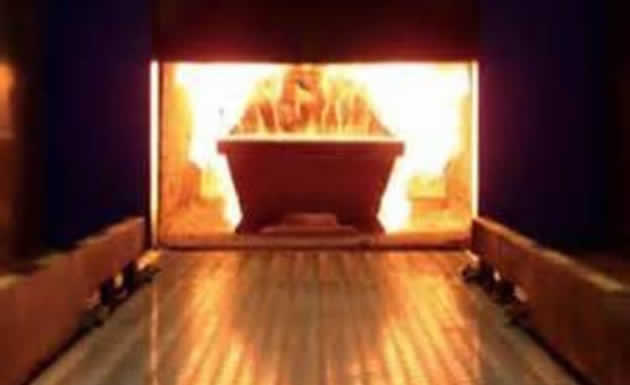

Zac’s boss was 80-years-old at the time of his death. They cremated him and Zac was there when the family went to throw Boss’ ashes into the Zambezi River. The family said this is what Boss Brian wanted: to let his ashes flow softly and silently with the waters of Africa. But Zac would have wanted to see his Boss buried in a real grave.

He never could understand this practice of burning a dead body until it becomes ashes then bury it in the ground or throw the ashes in the sea.

It was not respectful to the dead. How does one become an ancestor when all his remains are reduced to a box of ashes that Zac saw placed on the mantel piece for some time while waiting for all the family members to gather?

They kept the ashes in the house for six months until the family met again then travelled to a particular spot on the Zambezi River that Boss Brian had identified as his special place of final rest.

“I told Madam that what they do as white people is wrong. Why let the body and the spirit disappear like that?” he said he had asked her.

“She patted me on the shoulder gently and said, ‘Zac, this is what Brian wanted. I also want the same done to me. Ndakangozvigashira,” said VaZaka, meaning, he accepted the way white people bury their dead.

“Ungadii (what can you do)?” VaZaka continued, shaking his head sadly but also laughing, the way an old man does, when he carries memories of a good and a sad past. The look of age, and the emptiness of hope.

After Boss Brian died, Zac and Madam stayed together for three years. They spent the day either trying to experiment on a new dish or they did some gardening together.

In 2008, life in Zimbabwe changed. Sanctions imposed on Zimbabwe bit deeper. Money was printed until it could not be printed anymore.

Madam said her daughter wanted her in Canada. Life over there could be lonely, the weather was bad and there were no cooks, maids or gardeners, but health cover was good and there was plenty of food.

“Zac, I must go old boy,” she said. “If these knees still allow me to travel, I shall come back and see you.”

“But that was just a way of talking. Even if she was to come and visit, what would I be doing with her? There are times when a man must cry. I went back to my room and cried,” VaZaka said.

“Mainge mave kuda Madam?” asked Piri, meaning, “Were you in love with Madam?” And we all laughed. It was a relief to do so, because that look on VaZaka’s face was a sad one.

He shook his head and said, “Ah, what about my own wife back here? I came back in 2008. After all, was I meant to live with Boss Brian and Madam forever?”

We shook our heads and said no. My brother Sidney then stood up and speaking in his teacher’s voice he said, “Life changes and we must look back to the past and celebrate it. But we must also look to the future with hope. Otherwise, would we be here, preparing to honour the life our mother and welcome her spirit back to the people?”

The drums were warming around the fire. The smell of roast meat and sadza was in the air. Zac took a sip of warm beer and as if speaking to himself he said, “Madam is still alive. In Canada. She was not my boss. She was my friend. ”

- Dr Sekai Nzenza is writer and cultural critic

Comments