The complementary role of text in cartoons

Knowledge Mushowe

Knowledge Mushowe

Cartoonists are known primarily for their drawing.

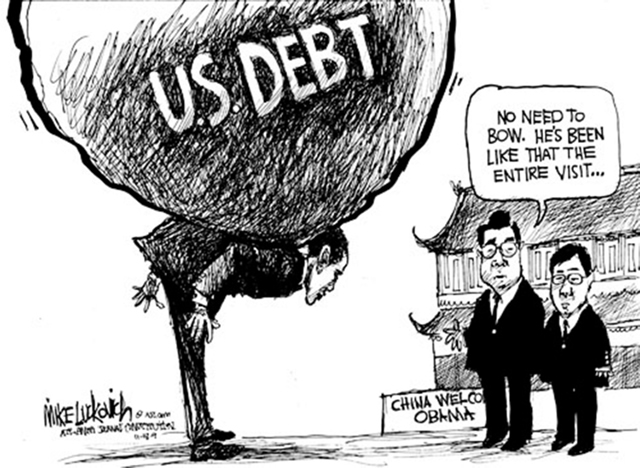

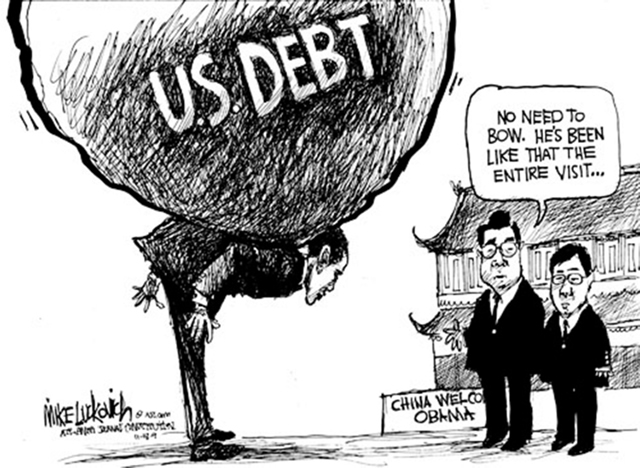

Little has been said about the amount or quality of text that accompanies their compositions.Editorial or political cartoons rarely look complete without some form of text playing a complementary role as an indicator, a speech bubble or an explanatory tag that helps the viewer to complete the overall meaning of an editorial cartoon.

The text itself is not really art, but the careful placing of it and the planning that goes into coming up with specific word combinations takes a lot of creativity.

The text is only secondary, as scientific analysis shows that readers often read the words last, having absorbed meaning from the visual components.

Visuals are the only indispensable part of an editorial cartoon, because some compositions are devoid of textual representations yet succeed in making sense to a reader.

In fact, some cartoonists use less and less text as they become more experienced, believing that it complicates some otherwise simple representations, and overrides the visuals on display.

But in truth, less text in an editorial cartoon is a clear testament of a cartoonist placing more faith in the visual components of their work.

For example, an inexperienced cartoonist may have a dialogue that starts with the words, “Hey, you seen to be down, what’s the matter with you today?”

If the same cartoonist were to be given an opportunity to recreate the composition later in their career, the above speech would not even be necessary.

The visual would be created in such a way that the second person would, given facial expressions, body language and gestures, a specific look that describes his emotional state.

Non-verbal, or paralinguistic features such as gestures and facial expressions provide the strongest cue on the meaning of an editorial cartoon.

Facial expressions, such as the line arc to represent a mouth and demonstrating happiness or sadness depending on its trajectory, have been used by cartoonists through time as visual symbols of human expression.

Others, like a circular-shaped mouth to depict worry, or anger suggested by multiple lines between the eyes ensure that readers understand the context of the editorial cartoon well before the overall meaning is impacted to their brains.

The editorial cartoon is a frozen frame with a limited window of time and space to make their point.

It is therefore vital that paralinguistic features presented in them direct the viewer towards the overall meaning.

The editorial cartoon tends to exaggerate shape, volume, size and form of components within it, yet the distortions act not as perplexing visual information, but well crafted “packages” all extenuating the meaning of the entire composition.

Exaggerations of the differences between physical power of a giant versus a minor, or the ironic reversal of their roles through body language provides an editorial cartoon no chance of presenting an ambiguous message.

Through irony, editorial cartoonists use non-verbal cues to present the direct opposite of what may be expected and consequently provide comic relief to their work.

Vectors, such as a person pointing towards some direction, transfers the focal point from the said person to whatever is highlighted in the general direction suggested by the hand gesture.

Lack of such paralinguistic features dampens meaning in an editorial cartoon, and the true emotional value of the composition may only lie inside the creator’s head.

Text itself also suggests paralinguistic features via punctuation marks.

A question mark, a coma, a hyphen or an exclamation mark gives cues about tone of voice.

An exclamation mark is perhaps the most revealing, because a raised voice indicates a departure from the “normal”.

Scholars Davies and Widdowson underscore the importance of paralinguistic features by saying that the actual phonic realisation of language element is only one component communication.

The features are used in editorial cartooning to convey a subject’s intentions and/or feelings.

Without paralinguistic features in editorial cartoons, emotions such politeness, anger, sorrow, anxiety, uncertainty, interest or lack of it, disagreement, criticism or urgency may not be so clear to a viewer and meaning becomes rather vague.

Semiotics, the study of signs, identifies three categories of non-verbal cues found in editorial cartoons – kinesics, proxemics and artefacts.

Kinesics is a study of body language that analyses the implied meaning suggested by the movement of the hands, face, legs and eyes.

The posture or movement of the body as a whole is a visual cue whose emotional and psychological meaning is seen in semiotics as vital to understanding of overall context.

Kinesics is made up of five sub-categories – emblem, illustrators, affect displays, regulators and adaptors.

Emblems are signs, or insignia, pieces of visual data that are informative, and provide the cartoon with the basis of the composition.

Emblems typically answer the questions, “what scene is depicted?”, and “who is doing what with what?”

Illustrators are labels that qualify the visual information by being descriptive.

Affect displays are typically illustrated by the example of a beautiful woman stroking her hands around a male subject’s face.

They are illusions on movement designed to provoke a response.

Regulators and adapters are the facial expressions and body movements designed to show control or lack of it, as reactive behaviour.

Proxemics studies space management. The amount of space between a subject and another or other things may suggest intimacy, a personal relationship, a social or public setting.

Artefacts, fixed features such as static architectural structures, semi-fixed objects, such as furniture and clothing are non-verbal cues that contribute to the overall meaning of a composition.

Comments