The changing role of men in parenting

Sekai Nzenza on Wednesday

A young couple accompanied by two children came through the arrival gate at Harare International Airport last week. They parked their luggage trolley next to us.

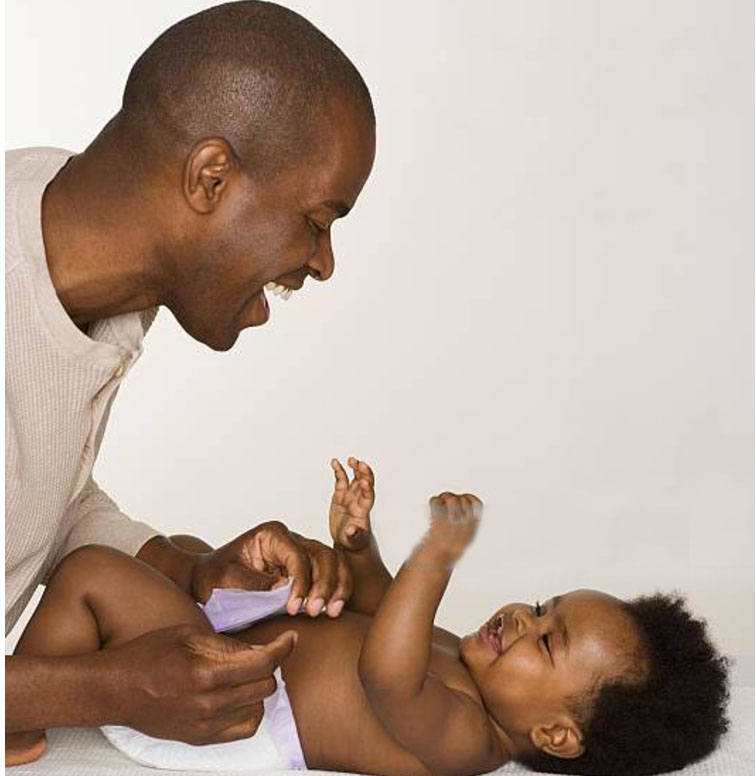

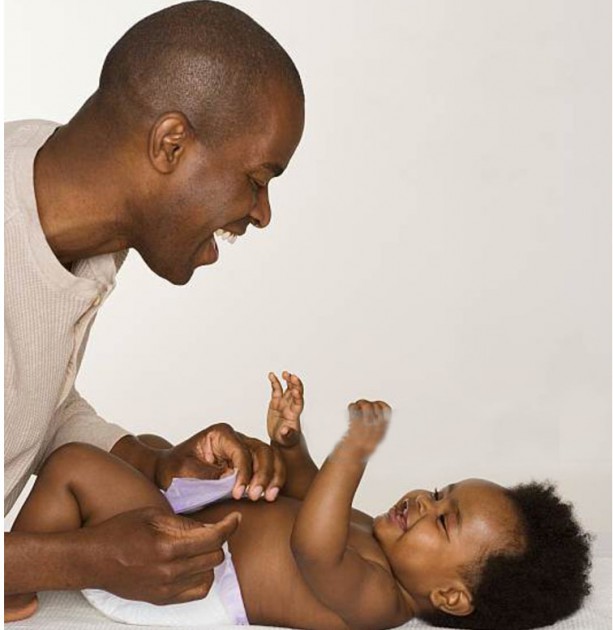

It was the father who quickly picked up the baby from the pram, placed her on the bench and started changing the baby’s nappy.

They were speaking in English to each other. We quickly assumed that these were Zimbabweans who had lived overseas for a long time.

The wife was possibly in her early 30s, wearing tight jeans and red-coloured stiletto high heels, a white shirt and red waistcoat matching with her lipstick.

She looked angry and irritable telling her husband that the person who was meant to pick them up was late. The baby in the pram was a girl toddler and the other one standing restlessly next to her mum was about five.

She carried a pink backpack and a big brown Teddy bear. The plane had arrived from Dubai. I was at the airport with my cousins Piri and Reuben to pick up friends of Reuben from America coming to stay with him during the forthcoming Heroes’ and Defence Forces holidays.

Reuben said his friends would have lots of luggage, so he wanted two cars waiting for them at the airport.

Piri came along too because this was another opportunity to see an aeroplane.

Our visitors were taking too long to come out of the airport.

We sat on the side bench facing the new arrivals while Reuben paced up and down checking the entrance for his friends.

The young couple and its two children stood next to us.

Piri did not move from her seat to give them room to sit down. I did.

We then watched the man change the nappy while the baby gently kicked at Piri’s legs. The wife stood by, chewing gum and clutching tightly a huge red handbag.

“Honey, it’s just wet. Nothing serious,” the man said, laughing and putting a clean nappy on.

The wife said nothing and kept on chewing gum.

“Mummy, how long are your relatives going to take to pick us up?” said the little girl.

“Sweetheart, I have already told you that I do not know. Ask your Dad. He knows the people who are supposed to pick us up.”

“Dad, when are they coming?” the little girl asked.

“Soon darling. Let me just finish changing your sister’s nappy and I will call them,” he said.

“We can just get a taxi,” said the little girl.

“I don´t like standing here for hours with all these strange people staring at me.”

“I know darling. I know. Me too. I want to get out of this place. I am exhausted,” the mother said.

We were pretending not to listen to the conversation. But we could not avoid listening.

“Ko sei uri kuregedza murume achichinja mwana napkin?” Piri asked the mother of the children, meaning, why is the man is changing the baby’s napkin. The mother said, “Excuse me?” Piri asked the same question again, this time speaking slowly.

I then translated, in case our assumption that they were Zimbabwean Shona speakers was wrong. There was a pause. Then the lady smiled and said it was okay, she understood Shona perfectly.

She said the reason why she did not respond immediately had something to do with not knowing Piri and also wondering what answer she could give.

Speaking in English she said, “Stanley is much better at changing nappies when there is no change table. That is why he does it.”

“But dad changes nappies all the time. He used to change mine too when I was a baby,” said the five-year-old. At this point, Reuben joined us.

“Oh, dad changed your nappy too when you were a baby? Good on you daddy!” Reuben said and he did a fist hand touch with Stanley. Standing up and folding the smelly wet nappy, Stanley said, “Hey buddy, what can you do when you are in the Diaspora?”

The two of them then laughed out loud, like they knew each other from a long time ago.

“I know the story mate, I know the story. Once you go to the Diaspora, they make you change nappies, cook, wash, sweep. You do everything man.

“We stop being men once we get on these planes,” Reuben said.

“I am Reuben by the way.”

Stanley and Reuben continued talking as they walked around looking for a bin to place the dirty nappy. Stanley’s wife then started texting to someone.

“Sis, vakadzi ava vari kujaidzwa, kuti murume chinja napkin ivo varipo? Varungu? These women are being spoilt. Why would men change nappies when the women are there? Are they Europeans?” Piri asked.

“But there is nothing wrong with a father doing some parenting. This promotes bonding between fathers and their children,” I said.

“What bonding? Baba is baba. He is just there. What parenting do you want from him as long as he goes to work to feed the family?” Piri asked.

I told her that used to be the case. Not anymore. When I was growing up in the village, I hardly ever got to know my father well, let alone imagine him changing a baby’s nappy. It was unheard of and possibly taboo. I do not recall my father holding me in his arms when I was little.

But then, you could say, children do not remember that anyway. But he could have held me when I was four or five, since I was very small and skinny.

I do not remember that happening.

My father used to come home on Rhodes and Founders’ Day.

I have vivid memories of him arriving home wearing a suit, white shirt and a tie, carrying some heavy groceries. We rushed to shake his hand shouting “Mauya Baba!” Welcome Baba. We probably hugged his legs and he shook hands with us.

May be picked one of us and held her in the air for a while. Maybe. This could be just be an imagination or fantasy on my part. If my father picked up any child, it would have to be Vongai, Raviro or Rumbi, because they were the youngest. Not me. There were many of us children. My father shook hands with us.

When the excitement of his arrival settled down, we all took turns to say, “Makadii Baba?” and he would reply to each one of us, making eye contact and saying he was well.

After that, we left him with my mother, Mbuya VaMandirowesa, Sekuru Dickson and others. Mbuya or my mother ordered a chicken to be killed. The following day it was the goat that died to celebrate my father’s visit.

We did not get any closer to our father during his stay. He dressed up in his nice khaki pants and white shirt with no tie.

Then he went to the dare, the men’s meeting place to greet Sekuru Mhofu, our oldest grandfather.

Sekuru Mhofu did carpentry and iron smelting of hoes and axes at the dare. My father talked with sekuru and the other uncles for hours. Then the women elders joined them under a tree to drink beer and celebrate the arrival of all the sons who worked in Salisbury (Harare) Bulawayo, Gwelo, (Gweru) Fort Victoria (Masvingo) or the other towns that were known by their colonial names in those days.

They drank, talked, laughed, sang and danced till late into the night.

When the holiday period was over, we all gathered in Mbuya VaMandirowesa’s hut to say goodbye to our father and the uncles. There were many people in the round hut. Mbuya, sekuru and the other elders then spoke to the ancestors, asking them to protect the sons who were now going back to the city kunoshava, to work.

Since there was no cash in the village, my father and all the other men went to work so they could pay the colonial land, dog, and hut, cattle and bicycle taxes.

My father left and we did not see him again until Christmas. After his death, I realised that I hardly knew my father.

Years later, we see young fathers spending more time with their children and even changing nappies.

Circumstances have forced them to do parenting to their children.

In Zimbabwe, we have a culture of maids and relatives who help with parenting. You hardly see a man changing a nappy. But you might see them cooking, bathing and feeding the children.

Quite often, you see men with their young children shopping or playing together at home.

Parenting by men is culturally new. We will do well for the children if we learn to balance and embrace this change.

- Dr Sekai Nzenza is a writer and cultural critic.

Comments