Technology enhances productivity

Charles Dhewa

Charles Dhewa

While more than 70 percent of food produced in Zimbabwe comes from the smallholder farming sector, improvements in crop varieties and livestock breeds have not been matched with improvements in tools and production methods.

Important activities like ploughing, planting, weeding, harvesting and storage are still dominated by ancient tools like ploughs and hoes. Unfortunately most farmers do not have the capacity to cost all these things. Thus small-scale farmers may think it is expensive to acquire and use a tractor compared to draught power because no one has shown them figures proving otherwise.

The lack of equipment has directly impacted on acreage utilised each farming season. “Due to inappropriate and absence of equipment some farmers end up farming on one hectare instead of five hectares,” said one farmer from Guruve.

It also directly affects quality and quantity of yield.

“Where you don’t have a boom spray you engage people to use a knapsack spray which is costly because some people charge per drum. On the other hand with a boom spray you can complete two and half drums in one hour. Conversely, you need two to three people to do a drum and because they sometimes get tired they end up not doing things efficiently. Using an automated boom spray which is calibrated ensures uniform application of chemicals as compared to a manually used knapsack sprayer which depends on the worker,” added another farmer from Macheke.

According to a farmer in Mazowe, one of the crops requiring the best land preparation is the potato, if one is going to get optimum yields. However, to get an appropriate fine tilth you need a ripper, roller, disk and gang tiller which can break down the soil to fine tilth. In addition, the right equipment enables ridging at the appropriate time with adequate soil cover. The bigger the ridge the more yield and the more protection for the potato from sun-burn. Without good land preparation you harvest 15–25 tons of potatoes per hectare compared to one using good equipment to prepare the soil who can achieve 40–45 tons per hectare.

Problems with inconsistency in technology

While the plough is used mostly for ploughing and planting as well as cultivating in some instances, the hoe is used for digging holes, re-planting (kukavira) and mainly for weeding. Using these different tools on one piece of land affects the precise depth of seed. Since there is a mismatch between planting depth and spacing, at least 30 percent of the potential yield is lost through poor germination and weeding. These issues can only be unearthed through careful research on all these processes in order to design solutions.

Given the diversity of climatic conditions, soils, crops varieties and animal breeds we should be having an equally diverse range of tools. At the moment, the most popular tools in smallholder agriculture are the plough, the hoe and, to a lesser extent, the cultivator.

With the expansion of conservation agriculture, let us see how this practice can be integrated with other labour-saving technologies. Farmers should see sense in digging holes during planting and then using a cultivator to fight weeds. This saves a lot of time. ur engineers are still to design appropriate equipment.

With the expansion of conservation agriculture, let us see how this practice can be integrated with other labour-saving technologies. Farmers should see sense in digging holes during planting and then using a cultivator to fight weeds. This saves a lot of time. ur engineers are still to design appropriate equipment.

Gathering the harvest

Small grains are still being harvested using knives and this may be why farmers shun them. Imagine how long it would take to harvest 40 hectares of rapoko or nyauthi. Maize is still being cut and arranged into bunches around which people can then work to retrieve maize cobs from the husks.

Some organisations are trying to promote the traditional granary (dura/isiphala) as something very creative, a big disadvantage of these granaries is that the quality of produce cannot be checked regularly. In most cases farmers discover that 50 percent of the maize in the granary has been damaged beyond repair within four months.

Farmers incur losses in harvesting sweet potatoes where a quarter is lost when hoes and ploughs are used. There should be appropriate harvesting technology which lifts the tubers gently from the ground without damaging the tubers.

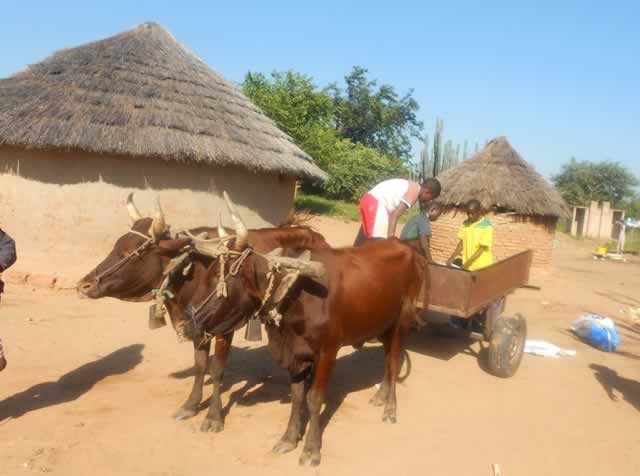

Scotch carts are used to carry commodities from the field to the homestead, followed by packing into baskets, two-litre tins, 50kg bags and then onto lorries or public transport en-route to the market. All this contributes to enormous losses.

Necessity for separating tools for crops from tools for livestock

Since crop production relies too much on draught power (cattle), the Foot and Mouth disease currently decimating our cattle is likely to negatively affect crop production. As a resilience strategy, crop production should have its own technologies independent of livestock. Instead of relying on draught power, why do farmers not sell 10 cattle and buy a tractor and save some more cattle for the market and other uses (milk, beef, skins, etc)? This is an investment dynamism which farmers are yet to learn.

Role for gender activists and importance of correct technology sequencing

Gender activities should be seen to advocate strongly for labour-saving technology in the agriculture sector. It is now common knowledge that 60 percent of the nation’s food is produced by women. But as along as agriculture is riddled with old and inefficient technologies, farming will remain a burden for women. Development organisations should come up with ways of enabling women to access appropriate labour saving technology.

Some contracting models are more interested in giving inputs as opposed to technology that will assist farmers in producing and harvesting. These companies start blaming farmers for poor quality produce forgetting that things went wrong during planting and harvesting. It not just seed and chemicals that ensure productivity but all kinds of technologies that should be spread across the entire value chain. At the moment, when all other inputs are available and you remove technology, yields can go down by 30 percent.

Need for relevant technology centres and platforms

Seed houses and research institutions seem to focus on researching different crop varieties and livestock breeds but there isn’t as much research on equipment and opportunity costs of relying on inefficient equipment. Such research should be used as a platform for crafting business models that can awaken farmers to the benefits of adopting new, efficient technology.

Financial institutions will then be persuaded to support farmers in accessing improved technology on the understanding that good technology will drive productivity which enables loan repayment. One of the reasons farmers end up side-marketing is because they produce far less yield than was contracted and feel there is no point in giving such low yield to the contractor when there is a big remainder still to be accounted for.

Opportunities for agricultural equipment providers

Just as there are companies specialising on hiring out cars, there should be a business model for hiring out agricultural equipment. Equipment companies can locate themselves in farming areas where they can hire out equipment to farmers. Some farmers may embrace hire purchase models where the equipment belongs to the company until the farmer has paid for it. This will ensure companies have a sense of the suitability of their equipment.

Rural industrialisation through agricultural technology

Technology can be another way for rural industrialisation. Efficient tools ensure constant supply of the right quantities for small to medium processing enterprises. In our call for value addition, we have to focus on the right production technology to avoid a mismatch between production and processing. Technologies should support each other along the value chain – production, transporting, grading, processing, packaging, etc.

With efficient technology on the production side, there is high potential for employment creation upstream (from the bottom up). At the moment, due to poor on-farm technology, it is difficult for farmers to supply sufficient quantities of commodities that can keep factories functioning.

The announcement that Brazil will soon release the remaining agricultural equipment to Zimbabwe worth $60 million under the More-Food Africa programme to support small-scale farmers. The equipment is a great starting point. With more such complementary programmes a true agricultural revolution of unimagined levels will occur catapulting Zimbabwe to achieve high food security levels at the household and national levels.

Charles Dhewa is a proactive knowledge management specialist and chief executive officer of Knowledge Transfer Africa (Pvt) whose flagship eMKambo has a presence in more than 20 agricultural markets in Zimbabwe. Feedback: [email protected]

Comments