Skokiaan, hymns and textual healing

Stanely Mushava Literature Today

Zimbabwe’s social memory can be unwound, mood for mood, from the spool of her music dynasties. Mbira poetics in the moonshine, mid-century township culture, chimurenga renaissance, gospel, jit, sungura and dancehall are all genealogies of the Zimbabwean spirit. Lately, biographers, historians and insiders have converged around this aural archive to map the cultural connections of the children of tribulation.

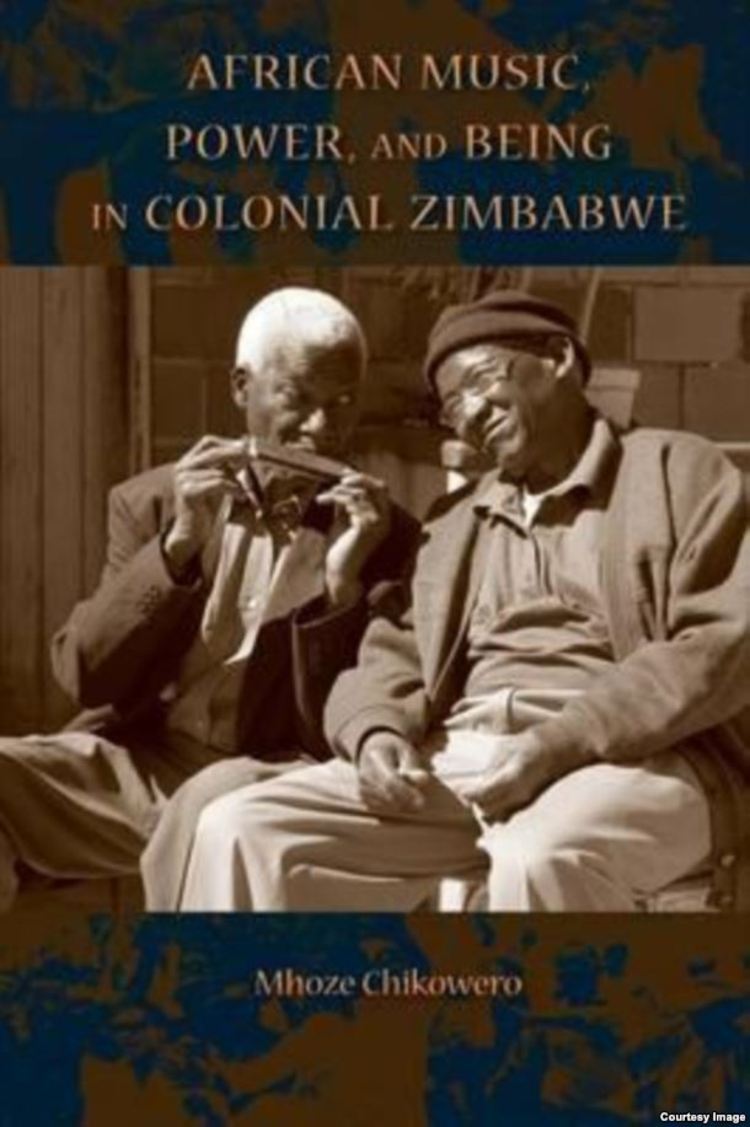

We have kept track of this canon, notably the latest books by Banning Eyre, Fred Zindi, Joyce Jenje-Makwenda and Shepherd Mutamba, in these columns. But US-based historian Prof Mhoze Chikowero’s book, “African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe,” (2016) is easily one of the most ambitious efforts in this league.

Chikowero deploys his mastery of history, an intimate knowledge of Zimbabwean music and a confessional reading of the indigenous belief system for a memorable feat in ethnomusicology. Set between the origins of Rhodesia and the children of tribulation’s final birth pangs for Zimbabwe, the book is as much about the music as it is about the nation.

While a lot of colonial hindsight is not at home in territories beyond simple truths, Chikowero ventures into the covert layers of cultural imperialism. His erudite, if insistently editorialised, history of Zimbabwean music attacks settler iconoclasm, Rhodesian incest between Church and State, and the bastardisation of the African and his history.

Chikowero interprets the missionary conquest against indigenous culture, including music and dance, not only as sacrilege but deliberate erasure of African ways of being, supplanting them with a Euro-themed centre.

Early Rhodesia spawned fears of “mbirapocalypse,” as the flagship Shona instrument, ngoma (drum), hosho (rattles), hwamanda (horn) and companion pieces were marked for extinction by settler authorities.

Missionaries come across in “African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe” as colonial proxies, demonising everything black and fetishising everything white, effectively distorting the gospel into a subtext of European imperialism.

Crucially, Chikowero observes, white settlers were anxious to obliterate the local climate of faith because it had been the inspiration of the 1896 Chindunduma Revolt (Chimurenga/Umvukela). Traditional instruments became a target of Rhodesian iconoclasm because they commanded a key stake in the indigenous spiritual regimen.

Chikowero outlines the missionary charge sheet, collecting taxes, and administering statutory destocking, cattle dipping, forced labour and agricultural edicts for church and state.

In the vastly diverting natural scenery of Mashonaland, racist missionaries saw the African as the only defect to be regretted. He had to be tamed, a task that partly meant destroying every relic of his culture and appropriating him for Rhodesia’s extractive economy.

The enforcement of conscience in Rhodesia is an enduring subject of interest. Some feel that Christianity is a beneficiary of colonial privileges which ought to be revoked. I feel that missionary atrocities are not so much in the Christianisation of the African but in the Europeanisation of Christianity for the dehumanisation of the African.

That, in a free dispensation, mapping religion in terms of geographic assumptions and enforcing conscience would be in itself a relapse to dark Rhodesia. The bad vibrations were not in Africans singing “Amazing Grace,” so far as the mode was spiritual rather than statutory, but in Africans belting out “Rule, Britannia, Rule” in either mode.

Chikowero’s implied juxtaposition of polar extremes, the truth claims of the indigenous belief system on one hand and missionary atrocities on the other hand, inadvertently primes the reader to judge the essence of “the African High God” against a misrepresentation of “the Christian God.”

Musicians within the Christian tradition today regard these supposedly regional deities as one omnipresent entity and, in defiance of racist missionaries, invoke Him with the instruments closer to their hearts, including mbira, hosho, hwamanda and ngomarungundu.

This transition is the subject of Chikowero’s second chapter. Having failed to move African souls with transliterated hymns, the missionaries set about “refixing” Christian songs to indigenous folk tunes.

Noted mbira exponent, the late Dumi Maraire, and others lent their hands to this project but the breakout success belonged to the Vabvuwi and Ruwadzano guilds of the Methodist church whose spontaneous African praises were readily appropriated by the African independent churches.

The African independent church and its latter-day counterpart, the charismatic mega-church, provide a nationalist counter-script to the erroneous assumption of Christianity as inexorably European.

The latter church’s emphasis on faith as a question of individual conviction rather than social convention, successfully deviating from the mainline method, also challenge the assumption that Christianity is a residue of colonial privilege.

Zimbabwe’s foremost gospel artiste Charles Charamba shares Chikowero’s denunciation of the missionary crusade against traditional instruments and has mastered the indigenous sound even as he questions ancestral worship, and affirms the divinity and universality of Jesus.

His South African counterpart Solly Mahlangu addresses both the white missionary and black sceptical in an Afro-themed spiritual: “When Jesus came, He came down from heaven; when He landed, He landed in Israel; when there was trouble, He came down to Africa; so we must praise Him, praise Him in an African way.”

Mid-century subcultures starring Dorothy Masuka, August Musarurwa and others were borne out of urban dislocation hence the convergence of music, sex, gang culture and the potent, backyard brew.

A whole chapter is dedicated to Musarurwa’s phenomenal jazz instrumental, “Skokiian,” which ran into a hundred covers drew homage from major artistes such as Louis Armstrong.

Chikowero bemoans imperialistic blatant “othering” in that Musarurwa’s instrumental became the blank slate for exotic fantasies about Africa by foreign artistes. A Florida couple cashed in on the inspiration of these covers, enacting “Africa in miniature” with an unpartitioned zoo where animals coexisted with black people.

On the cultural front, the crowning accomplishment in Zimbabwe’s political awakening was the upsurge of Chimurenga music in the 1960s. Thomas Mapfumo’s Hallelujah Chicken Run Band transposed the majestic mbira in guitar riffs and turned the Harare hit parade on its head.

The revolt, outgrowing Western covers for an indigenous feel, was instrumental as it was lyrical. Mapfumo had occasional brushes with the censors and the police for daring Ian Smith in songs such as “Pamuromo Chete” and “Tumira Vana Kuhondo.”

Zexie Manatsa’s Green Arrows, banjo-strumming prodigies from Mhangura, became a national sensation with politically charged tracks like “Nyoka yeNdara,” “Mwana Waenda” and “Hangaiwa.” Chikowero interrogates the political economy of performance in Zimbabwe with a mastery of detail that is yet to be matched.

Comments