Sifting through130 years of African history

Bert van Sloteren Correspondent

This polemic longread takes a critical look at the differences in the discourse about Africa and about Europe. Comparing Africa and Europe 130 years ago and today, the book contains a passionate plea for greater respect for the different African cultures and languages and contends that a lack of such respect is one of the main factors impeding Africa’s development today.

This longread looks back at the past 130 years of African history. The period between 1885 and 1950 was the period of colonisation. The period between 1950 and 2015 was a period of decolonisation and independence. The book tries to answer the question why the progress in many parts of Africa has been relatively slow.

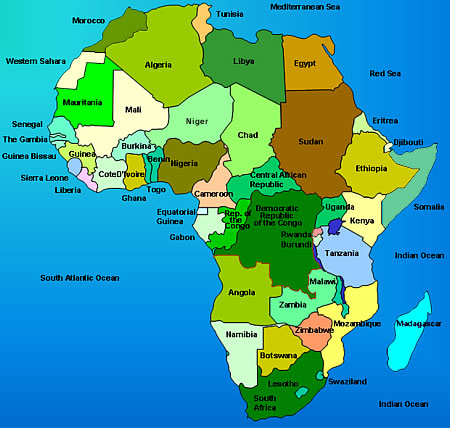

Starting point is “the curse of 1885”: the Berlin Conference, where Africa was carved up without any African involvement. The book shows how Africa has always had to deal with “second-hand” European ideologies and how Europe has introduced different words in dealing with its own people, different from what is being used for Africans. The longread examines these ideas and demonstrates their effects on Africa.

It shows how even today, when talking about African cultures, outdated and partly racists concepts are used. It introduces a more modern definition of culture and discusses the Hofstede model of describing cultures using various dimensions. The book calls for a study of African cultures using these modern theories. It points to the importance of nurturing languages and linguistic diversity – something which is happening in Europe, much more than in Africa.

The author points out how traditional anthropology and ethnolinguistics present a fragmented picture of African cultures. It calls for an African approach to social science that makes use of modern theories of culture and intercultural communication and that looks in an unbiased way at where the differences are between the peoples of Africa and where the commonalities lie.

The book examines the origins and the content of the idea of the Right to Self-Determination and points out that in the decolonisation process, that right was not respected. The author examines some of the reasons why things happened this way. He points to differences in the discourse about Africa and about Europe. In Europe, different ethnic groups are named as “peoples” – whereas in Africa, such groups are called “tribes” – an inherently racist form of reasoning that classifies Africans as being more primitive than Europeans.

Geopolitical and (racist) cultural ideas combined with ideas on African socialism, together form a potent but toxic cocktail, leading to the current consensus that sees ethnically more or less homogeneous nation states as necessary and good in Europe and in many other parts of the world – but not in Africa. A central thesis of the book is that this is one important explanation for Africa’s lack of progress, explaining to a large extent the nepotism and corruption so prevalent in Africa to this day.

The longread goes on discuss a few of the absurdities of African reality today, focusing on Nigeria, The Gambia, Botswana and the Hutu-Tutsi ethnic disaster. This latter is contrasted with the discourse about Croats and Serbs in Europe.

In order to overcome the “curse of 1885”, the author calls for:

- A study of African culture using modern theory of culture and intercultural communication;

- A study of African languages from an African perspective, looking not only at differences but also at commonalities and at possibilities for convergence, at any rate leading to a renaissance of African languages;

- A pan-Africanist perspective that does not gloss over differences but that respects and cherishes them, seeking to heal the wounds that were inflicted by the curse of 1885 and that is grounded in an appreciation of the uniqueness of all of Africa’s many peoples.

For some of Africa’s failed states, such as the Central African Republic, there seems to be no other option than to start to question the traditional borders. For some other countries, it might be possible to work towards models that would allow for increased regional autonomy. This requires a progressive type of nationalism, one that is not xenophobic, but that does not deny the fact that people are rooted in their own language and culture. – Fahamu.

Comments